Photos by Mark Peterson/Redux for Al Jazeera America

Produced by Joanna S. Kao, Lam Thuy Vo

Photo illustrations by Lam Thuy Vo

Edited by Alessandra Bastagli, Rhyne Piggott

Jimmie Mesis had been following the car for days. "Right now I can tell you that that vehicle is in a shopping center on Route 35," Mesis said. He couldn’t say much more because he was working on a case. Mesis is a private investigator, or PI.

He's been in the business for 35 years and seen a lot of changes. For an investigator like Mesis, there was never the glamour of James Bond or the IMF squad, but in one way the investigation game has become increasingly similar to that of spies on the silver screen: Technology is taking over.

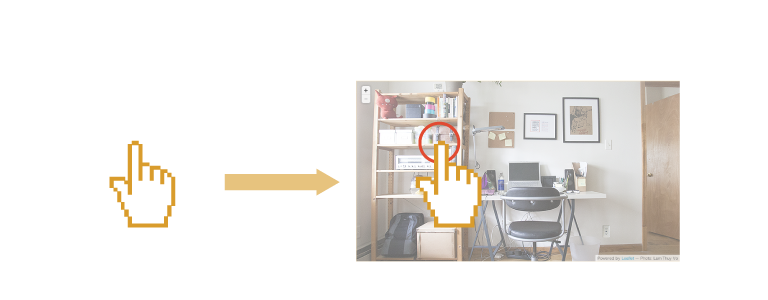

People have been following other people around to gather information since the dawn of civilization. But the difference here is that Mesis is not on foot. He’s not in a car. He’s not even in the neighborhood. He’s sitting in a chair at his desk, miles away from his quarry, in the basement of his red-brick home in suburban New Jersey.

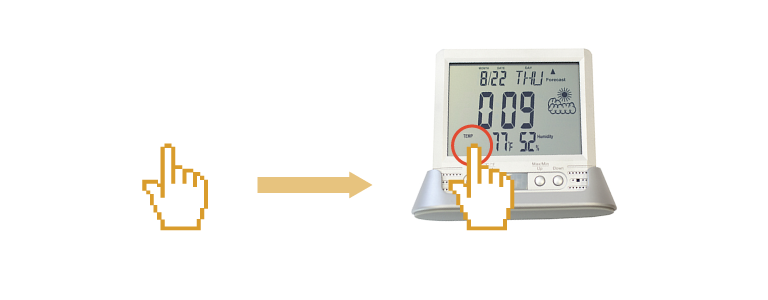

"I zoom in," Mesis says, referring to the red dot on the satellite map on his computer, "and that lets me know exactly where it is."

Mesis mouses over the dot and clicks. A window pops up containing information about the vehicle — its exact coordinates in longitude and latitude, its speed and the time it last moved — plus the battery life of the GPS device that's feeding him this information. The vehicle also has a unique seven-digit tracking number that allows Mesis to tell it apart from several other vehicles.

During his 34-year-long career, Mesis has worked on cases concerning all the classic scenarios: cheating spouses, fraudulent insurance claims, missing persons. He's also solved some unusual ones, like the $75,000 worth of stolen soft-drink syrup he recovered from a crime organization. He deployed hundreds of private investigators to bars on the night of a boxing match to find out if they were illegally screening the fight for customers. He was a security guard for Sylvester Stallone during the filming of Nighthawks.