Remembering the Boston Marathon bombing

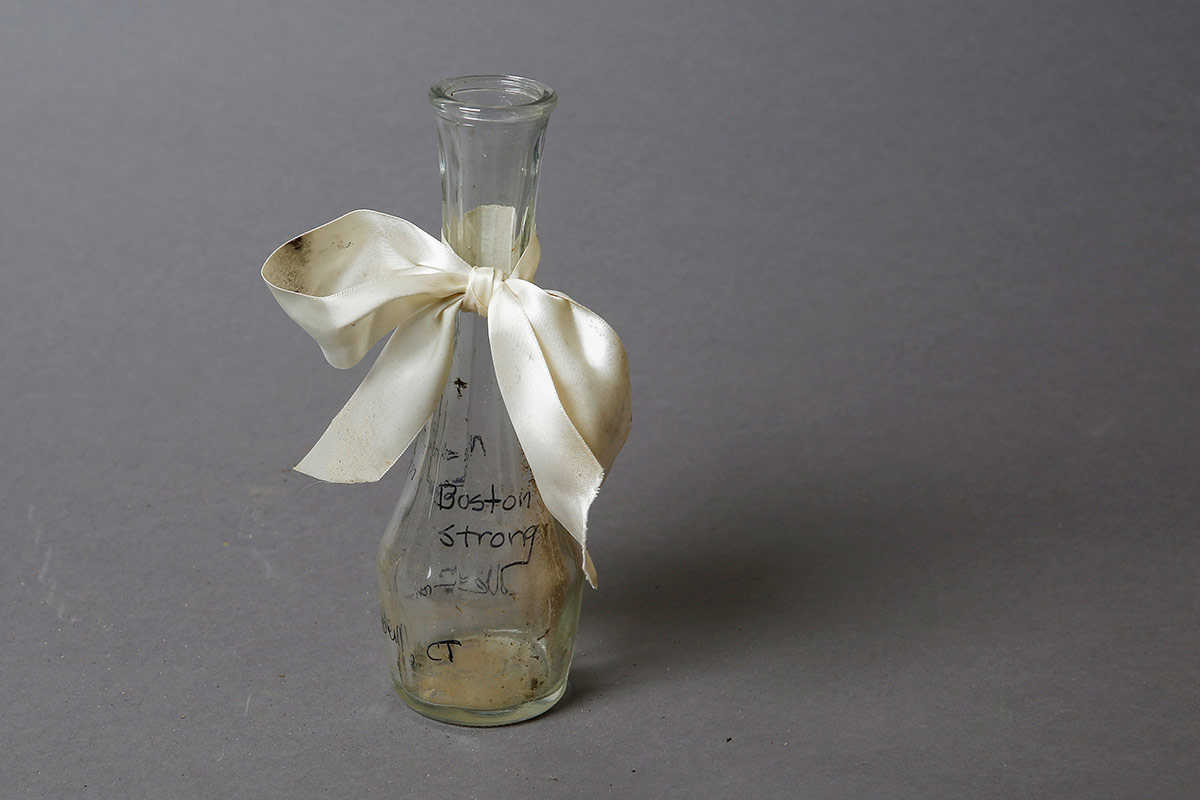

In the year since the Boston Marathon bombing, archivists have preserved the pieces of an impromptu memorial that rose at the site, as people left shirts, signs, banners, toys and other things expressing grief for the victims, often adorned with the saying "Boston Strong."

The artifacts are on display in Copley Square through May 11.

We are no longer accepting comments on this story.

On April 15, 2013, two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon.

Twelve seconds separated the first blast from the second. Al Jazeera asked some of the survivors who crossed the finish line during those 12 seconds how that moment changed their life in the past 12 months.

Submit your story at the bottom of this page.

Photos by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

ONE YEAR AGO: At left, police officers react to the first explosion and hear the second blast. Runner Bill Iffrig, then 78, was knocked down near the finish line. At right, a man comforts an injured woman near the site of the first bomb. (Click to enlarge images)

I did feel at times a sense of almost depression, and a kind of anxiety. Just hearing loud sounds . . . even now makes me jump a little bit. I went through all kinds of emotions the first month afterwards.

Read more

For the greater part of the year, I was hypersensitive to the word "Boston," and my nerves would be on edge when sudden loud noises, crashing sounds or fireworks were anywhere near. I was brought to tears regularly trying to talk about it.

Read more

Sharon Burns' tendinitis had tightened up so badly that she could barely move away from the direction of the bombs. Burns, who is going through radiation treatment for her breast cancer and is not running in this year's race, remembers being carried off to the side of the road by a Boston Marathon volunteer.

"The first thing in my mind was my family and my kids, and truly thinking I might not see them again," says Burns, 53, "and that I wouldn't be able to say goodbye."

I don't mind talking about it, because I don't want to forget it. I don't want it to go away. I don't want it to fade.

Read more

Every time he turns on his computer, Randy Clever is reminded of Boston. He keeps the names of the three people who died on a piece of paper taped to the right side of his monitor. He sees their names every day. If he really stops to think about last year's marathon, it makes him very sad. Clever, 64, intends to run in this year’s marathon for closure.

"It’s just part of your life now," he says. "You can go on living your life and doing what you do, but it’s all part of the makeup now of your background."

In those 12 seconds, I went from a sense of elation in knowing that I was going to finish the marathon to a sense of, 'How do I save my life?'

Read more

The joy Laurel Collins felt turning onto Boylston Street turned to memories of the World Trade Center on 9/11 as soon as she saw the first bomb go off. As she returns to Boston for this year’s marathon, the panic — and the feeling of helplessness in those moments — continues to stay with her.

"The 12 seconds are something I will never forget, but it was really finding out just how horrific the bombs were that has been the most difficult to deal with over this long term," says Collins, 62. "Maybe the biggest sense of closure is that they can do [the marathon] again without it becoming a horrible event; that they can bring it back to what it's supposed to be."

I realized that life is short. I realized that I was in danger; that a lot of people were in danger.

Read more

For a while, Julian Jauregui didn’t want to talk about what he went through at the finish line. Family and friends would ask the 63-year-old Peruvian national about the day, but reliving what he saw wasn’t easy. Like many other 2013 runners coming back for this year's race, he wants to enjoy all the work that goes into training for a marathon when he crosses the finish line this time.

"I just kept running faster to the finish line. And that's the time when I heard ambulances and the police, and I saw runners going to the finish line as quick as they could," Jauregui says. "That's when I thought of all my family. I thought about the people. I thought, 'This is not happening to me.' "

I remember feeling that I should have known that people were hurt. . . I had a day where I just couldn't do anything but weep, and I was really traumatized and terribly distressed by the whole experience.

Read more

Mentally and physically spent after 26-plus miles, Cory Maxfield’s brain went "dark" in the dozen seconds between the two bombs. It wasn’t until she was glued to the TV and YouTube, playing the sights of the wounded and sounds of the horrified on a loop, that her foggy recollection started to make more sense.

"Those 12 seconds made me more committed to making every second of my life count," says Maxfield, 55. "Those 12 seconds made me more resolved to return to Boston and run again. I refuse to allow an evil few to take the joy of running away from me."

It really was that sort of experience where you don't hear the sounds. You don't really know what's going on. You just are doing what you think is the right thing.

Read more

The hardest part for Vivek Shah, a Boston orthopedic surgeon at New England Baptist Hospital, is rehashing the events of April 15, 2013. Every patient who Googles him sees that the 37-year-old doctor ran in last year’s marathon, and proceeded to respond to the chaos. They all ask him about the experience.

"I would be lying if I said that my first thought was running toward the victims to help. I think that I was running toward the victims, praying that they weren't my family," says Shah, who is set on making this year’s marathon his final one. "It’s all stuff that I’ve seen during my residency, but we're not used to seeing it in the middle of the street."

How did the Boston Bombings change you in the last year?

The bombers took my legs, but everyone in Boston took care of me. They saved my life. They are the heroes, because they gave me an opportunity. They gave me the chance to prove that I — that we — are better than cowards with bombs. That we're not broken. And we're not afraid. We're stronger.

When Vivian Adkins crossed the finish line, she looked up into the bleachers and saw a cluster of bright yellow balloons flying through the smoke. Seeing balloons, usually a symbol of happiness, in a time of profound sadness, she says, remains the most searing image of those 12 seconds. It reminds her of a moment, she says, when she thought she might die.

"Those 12 seconds went from innocence — people just joking around, celebrating for their loves ones who finished — to wow, bad things can really happen in this world," Adkins, 44, says.