From carburetors to curling irons

ThesecretautomotivehistoryofDetroit'sHairWars

DETROIT — Less than 24 hours before Hair Wars, almost nothing was going as planned. The regular business of the A List 2 salon — a clamor of hip-hop, growling razors and whooshing hair dryers — was pushing into the evening, and the models and dancers were late for dress rehearsal. Ali Du'Shua, the salon's owner, was working on four or five heads of hair simultaneously, from an automobile executive's black short cut to a shoulder-length, candy-apple weave for the show. Between clips, he interrogated his designer on speakerphone about the missing costumes.

Du'Shua, a youthful, bearded man shaped like an oil drum, kept his composure amid the chaos, his fingers working quickly to snip out old extensions and shape wild, extravagant hairdos. Two stylists stepped in to shampoo and prep the girls, while model Keitha Caldwell fussed with the large fantasy hairpiece she'd be wearing down the runway the next day. The sculpture resembled a large jungle diorama built of moss and weeds and trimmed in fluorescent-green fake hair, with a propeller-fitted tank emerging diagonally from its center.

It had taken Du'Shua dozens of hours to create and build a piece just right for this year's "Salute to the Troops" theme at Hair Wars. With the help of an electrician, he'd gutted and rewired a remote-control toy tank and topped it off with a spray-painted popsicle-stick cross.

Long ago, when Du'Shua was still Chester "Chip" Lee Dixson, he knew his way around a real car motor. Fresh out of high school in 1978, he got married, enrolled in college and got a job at the Ford assembly plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The work was dirty and boring but also steady and well compensated.

About five years later, Dixson was laid off in a recessionary dip that signaled the U.S. auto industry's steep fall to come. There was no severance package, but his union contract mandated about two years of health benefits and "subpay" (80 percent of his salary), in addition to unemployment. "At that time we had the [Trade Readjustment Allowances, or TRA], and they'd pay for school if you decide to go take a trade," he says. When he saw the money hairdressers could make doing Jheri curl — $75 a head, six to seven people a day — he enrolled in cosmetology school and got Ford (via TRA) to pay his $2,500 tuition.

Dixson wasn't alone in this leap of faith and careers. To go from factory to salon is a surprisingly common path in Detroit. For African-Americans (83 percent of the city's 700,000 residents), hair is as much a part of the culture as automobiles and Motown, and many have found liberation and material comfort in the hair game.

Dixson was raised in Ann Arbor, in a tight-knit family focused on church and hard work. From an early age, he absorbed stories about factory work and women's hair. "My grandmother was doing press and curls for $5 in World War II, but a loaf of bread was 25 cents," Dixson says. "She worked in a hydromatics plant right outside Ypsi[lanti]. When they announced World War II, the plants were changed over in a week. The parts for cars were now for tanks."

For men graduating high school in the late 1970s, the local auto plants were an obvious choice. "You're actually feeling obligated back in those days, to try get a job like that, even if you're going to college. Before I went to Ford, I did security guard job and there was no benefits for that. So when I got married, I was like, 'Man, this security guard job making $5 an hour, that's not happenin.' "

The factory work was trying, even dangerous. Dixson remembers the heat on his arms and grease splattering his face and hair. The worst was the armature department, where Dixson once blacked out and, he believes, had a heart attack. On the carburetor line, he was constantly hunched over, clipping wires; and in "paint and pack," he put shocks through a room-sized washer. His last job in the plant was to inspect the same shocks under an infrared canopy.

Those five years at Ford shaped Dixson's worldview. He saw firsthand how work could unite different races and how well-paying jobs could transform people's lives. "If you look at the plants, they were in the inner city," he recalls. "It made you feel good. You go to the plants and you got two cars, a boat, a house — everything." Dixson saw his wages and benefits as outcomes of unionized labor. "Unfortunately, they're trying to get rid of unions now. A union represents the middle class."

Left: The Ford assembly line in 1975 at the historic River Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan, which dates back to 1918. Today, the plant employs about 1,000 women and men on each 10-hour shift. At a rate of one giant F150 per minute, the trucks’ boxes and cabs — previously assembled and disassembled — "get married" like steel Platonic halves. Long gone are the deafening, oily pneumatic machines of the 1970s; the plant is improbably quiet, clean, efficient and safe, though it sits on a polluted industrial expanse miles wide and deep. Right: An autoworker at Ford's plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan, in 1983.

(Click to enlarge images)

Local 600 of the United Auto Workers still bargains for 11,000 active factory laborers and white-collar employees in southeastern Michigan, most of them on Ford's payroll. The numbers are nothing like they used to be: down from nearly 100,000 members in the 1940s.

Ford is hiring again and Detroit is still largely a company town, according to Bernie Ricke, president of Local 600. But it'll never be like it was when Ricke first started out, when "you could go from one plant to another and get the same pay and benefits." Ford, GM and Chrysler, he says, "made their own parts back then, [but when] they slowly got out of the parts business, the density of union membership over a 30- to 40-year period dropped from over 80 percent to 20 percent." Since then, the auto industry has shrunk progressively, instituting decade-long hiring freezes and offering retirement incentives to avoid outright layoffs.

"Some of the things we did to save jobs, none of us wanted to do that, but it was the stark reality. That was the only way at that point. The way the economy was, it was the only logical thing to do," Ricke says.

For Dixson, his layoff from Ford came both as a shock and a relief. On the hot, slippery factory floor, he had hankered for cool air and cleaner surfaces. He wanted a chance to create something from start to finish, not just build a piece of a predetermined thing all day every day.

With his TRA money, Dixson graduated, got his hair license and rented a booth in a group salon until he could open his very own business, the self-referential Miss Chips, in Ypsilanti. Dixson loved wearing flashy clothes and befriending his clients and other hairdressers. The money was good, too — sometimes more than $300 a day (in 1980s dollars).

He became an expert in black hair and still expounds upon it like the best kind of scientist: precise and analytical, yet rapt, seduced by his subject. At beauty school, he familiarized himself with different kinds of hair, their textures and tendencies. "Some hair has dermis, and some races have a dermis and epidermis, so the length of the hair makes a difference," he says. "Then you have cowlicks, how the hair grows out the bulb. The thickness, the density of the hair makes a difference per square inch."

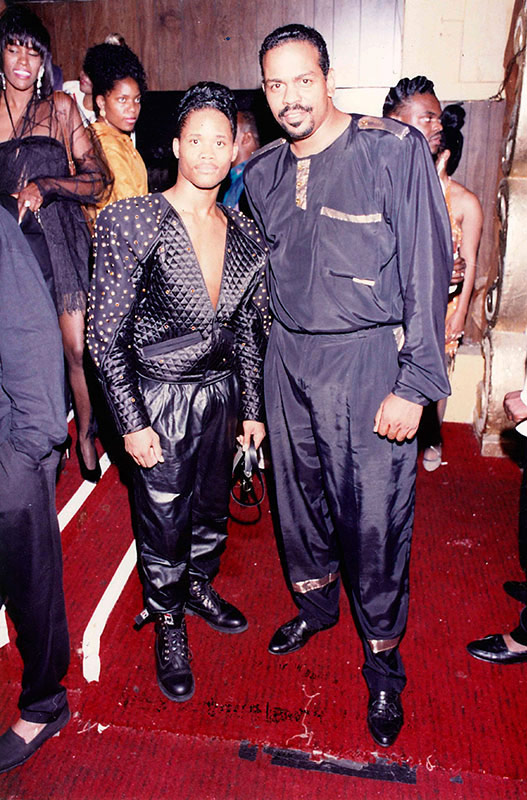

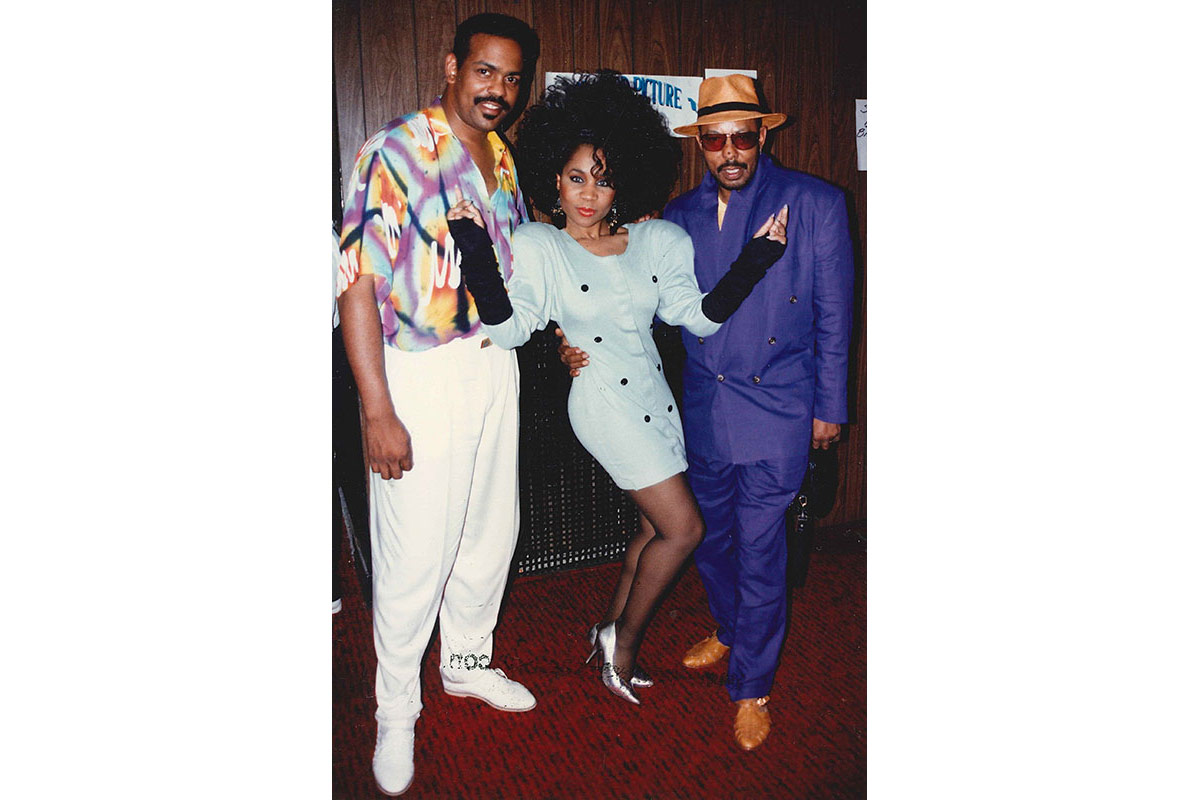

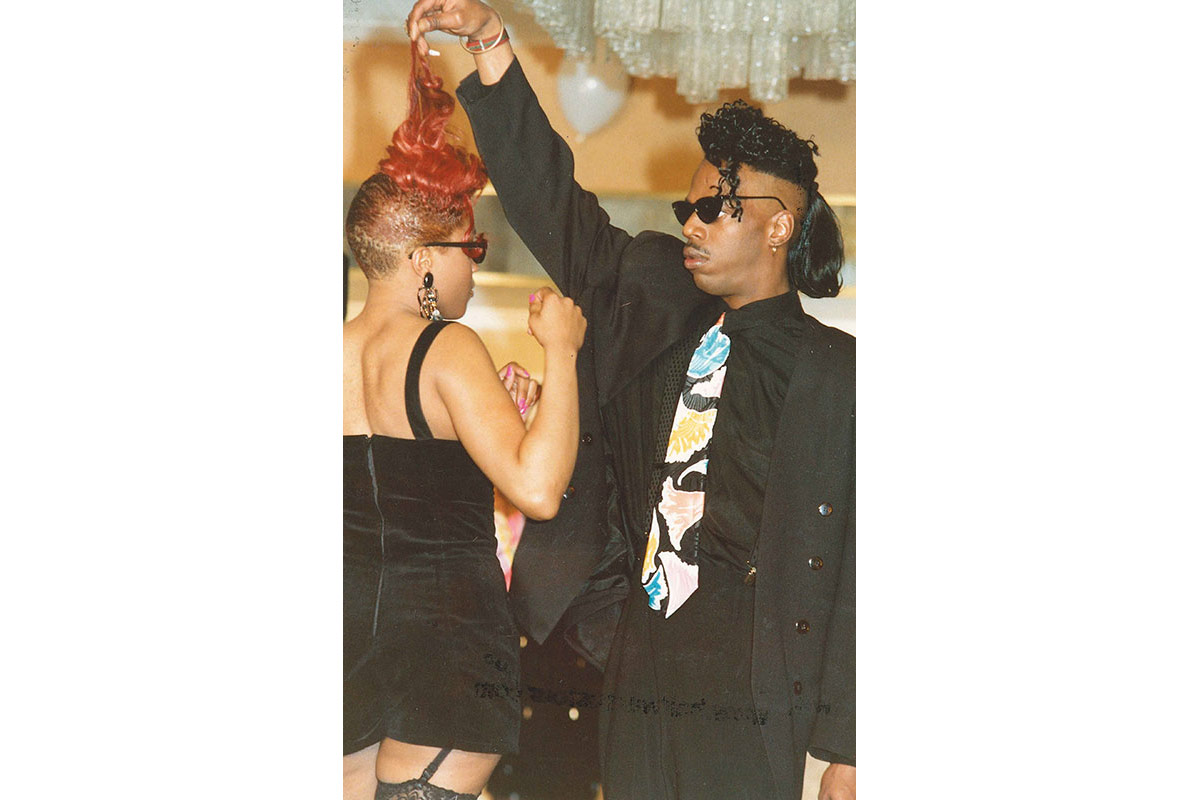

Dixson took his craft beyond the salon and into Detroit's nightclub scene, home to a nascent spectacle of flamboyant "hair entertainment." In 1985, he channeled his Motown idols and unleashed his hairstyling mojo in the first-ever nightclub hair show organized by local DJ David "Hump the Grinder the Sweet Spot Finder" Humphries, or "Hump" for short.

Listen: Hump's Hair Wars soundcheckA tall, mustachioed man with a perfect radio voice and doe eyes, Humphries had made rap history in 1984, when he worked on the Fresh Festival tour, featuring Run-DMC, the Fat Boys and Whodini. Back home in Detroit, Humphries was awed by the club kids boasting outrageous hairdos and clothes as they danced to early homegrown techno, or "real hard funk. I call it fast funk," Humphries says.

He'd felt a calling to promote. "These people have so much talent. Nobody was doing anything about it. They needed someone to corral them and put them out there." Humphries' informal nightclub act gained a following and soon evolved into Hair Wars, a runway pageant of "fantasy hair" creations paired with outlandish costumes, skits, dancing and original music.

Photo courtesy Hair Wars.

A few years into the hair-show craze, an old friend of Dixson's walked through the doors of Miss Chips. In the first week of classes at Alexander Beauty Academy, in Ann Arbor, Dixson had met another laid-off autoworker, a 300-pound bodybuilder who'd assembled carburetors and heat-coat alternators at Ford for six years. Now called Big Bad D (his legal name), the "biggest, baddest bodybuilder and hairstylist in America," he made Dixson an offer.

Thanks to his enormous physique, nearly floor-length braid and outrageous clothes — coats with curtain rods at the shoulders, animal skins hanging off his belt — Big Bad D had been discovered by a big-time hair-products mogul named Chappie Cannon Jr., a man infamous for his profligate habits and fleet of Rolls-Royces. As the spokesman for Cannon's company, American Beauty Products, Big Bad D had promoted and demonstrated the use of Jheri curl cream all over the world and now hoped to recruit Dixson as a fellow "platform artist."

Big Bad D's offer could not have come at a better time. Dixson had been served divorce papers on his birthday and felt depressed and isolated. "My oldest son, he's crying, making himself throw up at the school just to see me. It was a mess." He jumped on the chance to get some distance from the commotion at home and try something new, more creative and adventurous.

"I told him, 'Look, number one, you got to change your name. You gotta get an outfit. You can't come in here with no "Chester Dixson,"' " Big Bad D recalls. "I took him to my boy's place. He designed him some clothes. The day he started touring, he was signing autographs."

Dixson took the stage name Ali Du'Shua, after an Afro-Canadian ancestor, and adopted the stage persona of a ruffle-shirted "Prince of hair." Du'Shua and Big Bad D were on the road for almost three years, touring Paris, London and the Caribbean with American Beauty Products. They also toured with Hump's growing Hair Wars enterprise to cities like San Diego, Atlanta, Miami and Columbus, Ohio. "It was refreshing," Du'Shua says. "I had the best time of my life."

The early days of hair wars

Hair Wars just turned 29, a milestone that its aging fans and planners would rather bury in a deep vat of relaxer. This year's spectacle unfolded on May 4 at a hotel abutting a shopping mall in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn, home to the country's largest concentration of Arab-Americans and a parking lot away from a corporate tower bearing Ford's sparkly blue-and-chrome logo.

In a hotel room several hours before the show, hair entertainer Donell Danny Davis, aka 3D, presided over a fluorescent, Mardi Gras-themed collection of fantasy hair. (Only one of his creations, colored red, white and blue, was in line with the "Salute to the Troops" theme.) His dozen headpieces, built from yards of braided, bedazzled and blunt-cut weave, ranged from branching jester's hats to a tiered, yard-high column resembling Cousin It. A gaggle of young amateur and professional models swirled around Davis, choosing hairpieces and matching spandex outfits and applying thick eyeliner and lipstick.

Davis, 57, an Army dietician turned hairdresser, has technically retired to his home on Pilgrim Street, though he still cuts for a few friends and participates in Hair Wars. (He's also a stand-up comic.) For weeks, he labored over the hairpieces in his leaking basement, one wall covered in faded clippings and photos from his long career in hair. It was a lucrative profession when he got started in the 1980s, particularly at Vantinus, one of six 24-hour salons owned by Vantinus Johnson in Detroit. "It was just like a shift: morning, afternoons, and that's the way we were. We had people came in in the morning, we had people came in the afternoon, and at the midnight shift. Like if you worked at the auto plant and you got off at 10, 11, 12 o'clock, where you gonna go? If there's a place to be, you go. So actually, the evening shift made more money they just about anybody else, because they catered to the plants."

Round-the-clock hair was not uncommon in the '60s, '70s and '80s. Retired stylist and former Hair Wars regular Michael Horner built his reputation at an 4all-hours salon frequented by Smokey Robinson, The Temptations, B.B. King and "a lot of Ford workers." "We worked all kind o' hours. It was the love of doing the hair, plus making the money." Like Du'Shua and Big Bad D, Horner entered the hair game after a stint in the auto world, although his lasted only a few months.

Horner made his name in "finger waves," a glamorous style worn by Josephine Baker and Motown groups, and toured internationally as a platform artist for the Hawaiian Silky products company. Now 66, he keeps busy with his two teenagers (the other children are grown), painting elaborate, mixed-media canvases and playing the congas. In his kitchen-based salon the Saturday before Hair Wars, Horner gave a "comb-out" to longtime client Walter McKinny, a 60-year-old dandy with a pompadour and oily finger waves. McKinny has had the same hairdo since he was 13, when he became old enough to imitate his showbiz heroes.

"All the way through school, you know what I read on the walls? 'Black nappy-hair ugly nigger.' And when I seen Jackie Wilson and other groups on television and saw their hair, I said, 'That's what I want.' You know what, I'm gonna tell you what else I said. I said, 'I have never seen a white man's hair look good as mine in all of my life,' " McKinny recalls.

Hair Wars is a celebration and elaboration of black hair and a "body-positive" endorsement of every shape and weight. All this was on display in the backstage greenroom,eading up to showtime: 6:05 sharp, without fail. The stylists and their entourages filed in with giant makeup trunks and garment bags, unloading at their assigned folding tables and erecting ersatz makeup stations and curling-iron booths. Millions of selfies were taken in the span of a few hours.

Du'Shua arrived in a hoodie and sweatpants, exhausted from the night before. After hours of cutting and dyeing, he resorted to calling Triple A when he couldn't find the key to his car, and got home past midnight. His models and dancers looked comparatively fresh, decked out in camouflage jumpers hot off the costumier's ironing board. Keitha Caldwell, conduit for the jungle-tank fantasy hairpiece, changed into a revealing black-mesh catsuit and got a once-over in glitter by A List 2's resident makeup artist, Terrell "Adonnus" Webb.

The hotel ballroom was divided into two sections: reserved tables tracing the brightly lit runway and general seating farther back. The expensive seats cost $40 and were only about half-filled by middle-aged couples and groups of girlfriends proudly flaunting their cleavage. Humphries took the mike to introduce legendary songstress Martha Reeves, of Martha and the Vandellas fame, who'd "come to steal hairstyles!" and tolerate the DJ's obligatory intervention of "Dancing in the Streets."

Du'Shua and his suave parade were the final act before intermission. From the back of the runway, he directed a kaleidoscope of bodies and hair: a tall, sultry brunette; confident girls in red-and-green weave; a beefy car worker with his buxom fiancee; two dancers in cutout leotards; a skinny, tattooed man wearing braids; and a teenager in a flapper-era platinum 'do. Then the jungle-tank piece de resistance came out spinning on Caldwell's head, and Du'Shua ran onto the stage in camouflage cargo shorts and a black hunting vest but no shirt, wielding a hair dryer like a handgun and lip-synching "It's All About the Hair, Baby," an R&B anthem he'd composed and recorded with his son and the Funkadelics. The crowd loved it.

Listen: 'It's all about the hair, baby'

As Du'Shua and his crew caught their breath and posed for pictures backstage, the second half of Hair Wars rolled along. Davis came down the runway in a long, persimmon-hued three-piece suit; white alligator shoes; and sunglasses, flanked by girls in sequined spandex, their colorful hairpieces tilting earthward. The renowned stylist Little Willie presented several models dressed in tomboyish camo-casual, displaying flawless, street-ready hairdos to the tune of Bruno Mars' "Just the Way You Are." And Iraqi-American Raphael, 2010 gold medal winner at the World Championship of Fantasy Hair, exhibited a crew of slender models wearing elegant gowns and peacock-inspired hair sculptures — "Salute to the Troops" theme be damned.

Du'Shua was too exhausted to attend the after party at Moose's Martini Pub. He went straight to his hotel room and spent the next day at home in Southfield, a tranquil suburb northwest of Detroit. Back in the day, he says, hair shows had the feel of rock concerts, marked by random sex and lots of drugs. "You'd think someone piled flour on the counter. But Hump is one of the cleaner ones."

Hair Wars 2014

Like many Hair Wars veterans, Du'Shua leads a sleepy life outside the salon. He spends time with his children and grandchildren, practices muay Thai and identifies as a broadly spiritual "Muslim, Christian and Jew." He thinks a lot about his brother Mark Jr., a would-be hairdresser who died of an asthma attack just two days after finishing beauty school.

Du'Shua's three decades as a hair artist, promoter and hair-products entrepreneur (he ran his own line for 12 years) have treated him relatively well. He lives alone in a handsome, well-lit condo and drives a white, 2002 Mercedes, a step up from the dowdy Ford Escort he owned as a young man. Yet shortly after this year's Hair Wars show, Du'Shua had to close one of his two salons. The stylists and makeup artists of A List 2, who were each paying $150 per week to rent a booth, have now squeezed into A List 1, further down 6 Mile. Like everything else in Detroit, doing hair isn't what it used to be. More than a decade ago, Du'Shua earned as much as $90,000 per year, plus $10,000 in profits from his hair-products line, but business has slowed down considerably.

Black beauty salons are often glamorized, and exoticized, in movies and on TV, but they are fueled by long hours and good times in equal measure. Most stylists are independent contractors, not employees, which gives them the chance to set their own hours and rates but comes with the downside of no benefits or guaranteed pay. They rent booths in a salon and work constantly to promote themselves and attract and retain customers. In 2012, the median income for barbers, hairdressers and cosmetologists was just $22,770, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Hairstylists have no pension, no health insurance," Humphries says. "There's also chemical exposure. And foot problems from wearing fancy shoes or not working on [floor] pads."

About 76,000 hairdressers are working under an active license in the state of Michigan, most of them in and around Detroit, but black stylists feel pessimistic. "When I first came out of beauty school, the pay rivaled all the plants," says Bruce "Goldie" Stevens, a Hair Wars alumnus who clocked two weeks at GM right after high school, in 1989. "You were getting $65 easy for a hairstyle, 10 to 15 a day, but as soon as the plants collapsed, we felt the same collapse." Although Stevens doesn't regret his life in hair — "It was so glamorous compared to being in a gloomy plant" — he worries about the future. "Disability I miss. Medical coverage. Knowing what I know now, I probably would've stayed at the plant and just did hair on the side."

It's not only that the economy has taken a noticeable dive, nor that Detroit is bankrupt and under emergency management. Stevens, Du'Shua, Davis and Humphries also complain of regulatory changes and shifts in the manufacturing and distribution chains that have made life a lot harder for trained cosmetologists.

"At one time, they depended upon us for our skills, to be able to press and curl, but now you can go to the beauty supply and buy a wig and sew it in," Davis says. Du'Shua blames the mostly Korean-run beauty-supply stores for selling professional-grade chemicals directly to consumers and state inspectors for failing to enforce licensing requirements against "kitchen beauticians." "If I was to get a union together, like the Ford Motor Co. had," Du'Shua says, "I'd get together a bargaining committee that would definitely address that."

But his friend Big Bad D, who runs the BBD King hair-care line and conducts educational seminars for the general public, assigns equal blame to African-American stylists and product makers. In contrast to white hair salons, which always pushed shampoos and glossers on their clients, "we didn't understand the economics of selling beauty products," he says. "That's how the Koreans got so big: because they understood [customers are] gonna go to retail." He also believes the booth-rental system was the wrong way to go; instead, black salons should have supported their own by making full hires and paying benefits and commission.

Most of all, Big Bad D regrets the fact that so few manufacturers, distributors and suppliers of black-hair products are actually owned by black people, a subject touched on by Chris Rock's 2009 documentary, "Good Hair." "I could've made millions and millions if I sold to the Koreans, but I didn't do it. I saw all the black manufacturers go out of business," Big Bad D says says. His best-selling product, BBD King Stretch Growth Creme, reportedly sits on Condoleezza Rice's shelf.

The hair game isn't so different from factory life or any other kind of labor, according to Du’Shua, and black workers will continue to make their own way. "Detroit is a labor town. Labor jobs in the plants taught you that. To me, hair is a hustle. It's still a formal hustle to get your money," he says. "We as the African-American community is hustling by nature. When we were brought over here, we were free labor for America. We learned to hustle against the man."

Even if Du'Shua never sees another Mercedes, he is determined to keep doing hair. In the new economy of Detroit, which he describes as a postcapitalist experiment, "I might have to bring my prices down. I might be doing blow-dry and curl, shampoo and style and only get $45 now. I might have to go to $20 — but I guarantee you that I'll still survive." ◆

Correction: This story was updated to correct the city in which A List salon is located.