Radio on the Reservation

NativeAmericanstuneintoanold-fashionedtechnologythatkeepslanguages—andcommunities—alive

By Tristan Ahtone for Al Jazeera America

Photos by Tomo for Al Jazeera America

Graphics by Michael Keller, Alex Newman

Audio produced by Lam Thuy Vo

Produced by Joanna S. Kao

Edited by Katherine Lanpher, Mark Rykoff

Published on March 1, 2014

Click below to listen to a variety of Native American broadcasters throughout the nation.

Radio montageDust and diesel smells hung in the air as an 18-wheeler blasted through the tiny village of Kykotsmovi on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona. Just off the road, a dog whined before lying down in the sun. A light breeze blew sand off a nearby mesa, sending it to ping and shuffle against the khaki sagebrush. Then through the settling silence, the sounds of radio static — and suddenly, the voice of an announcer from the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia.

Arvin Fredricks put down his carving tools and turned up the volume.

“That’s my constant companion, the radio,” he said. “It’s all coming to me by way of this little box that’s playing it out to me, and I’m doing something else that I love to do.”

Fredricks owns a tire repair shop, but when nobody swings by for a quick fix or to air up, he carves wooden katsinas, little dolls of religious deities to the Hopi and artistic curiosities to tourists.

“This is what I do,” said Fredricks. “Especially when it’s a nice day, you’re out here in just your T-shirt, just waiting for a customer, and there’s my radio.”

About 7,000 people call the Hopi Reservation home, living in 12 villages spread across three mesas, nestled within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation in the northeast corner of Arizona. It’s isolated and sparse and boasts dramatic landscapes as well as limited access to Internet and even phone services.

As access to instant digital media and news spreads across the United States, tribal radio stations are a rich example of just how the digital divide continues to separate Native America from the United States and how tribes use technology often seen as outdated to bridge that gap.

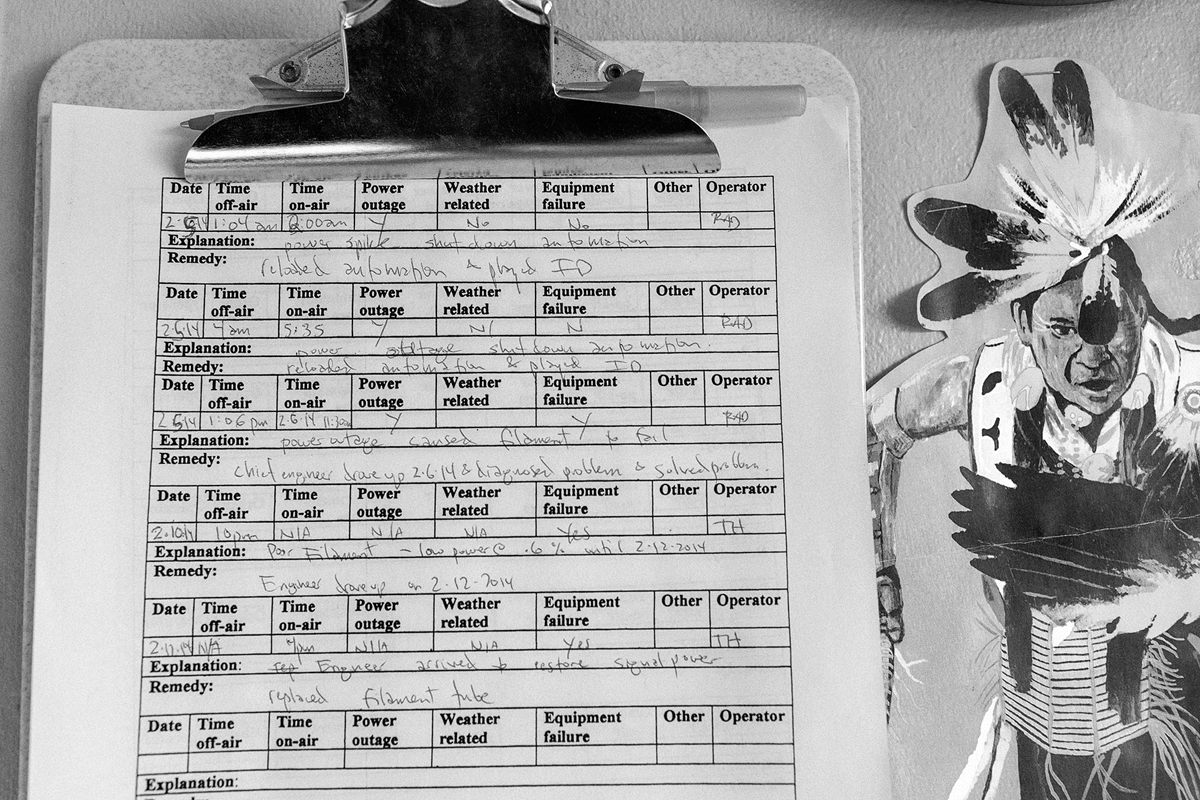

“There aren’t the basic emergency response services. There’s no fire department on Hopi,” said Richard Davis, manager for radio station KUYI, 88.1 on the dial, serving the Hopi reservation. “When there’s a wildfire, we’re going to be the only people that let folks know where it’s burning. When there are icy road conditions, we’re going to be the only folks letting people know where to drive a little more safely.”

When floods hit the reservation in 2009, KUYI became the lifeline many communities needed to survive. For nearly three weeks, plumbing was wiped out on one mesa, and the station broadcast where people could use bathrooms and get water. A year later, a blizzard left five-foot snowdrifts across the reservation, and KUYI became the only way tribal members knew where to pick up food air-dropped by the National Guard.

“Outside in the mainstream culture, a lot of folks think radio is dead, but tribal radio is very strong,” said Davis. “We really are the lifeblood of what’s going on.”

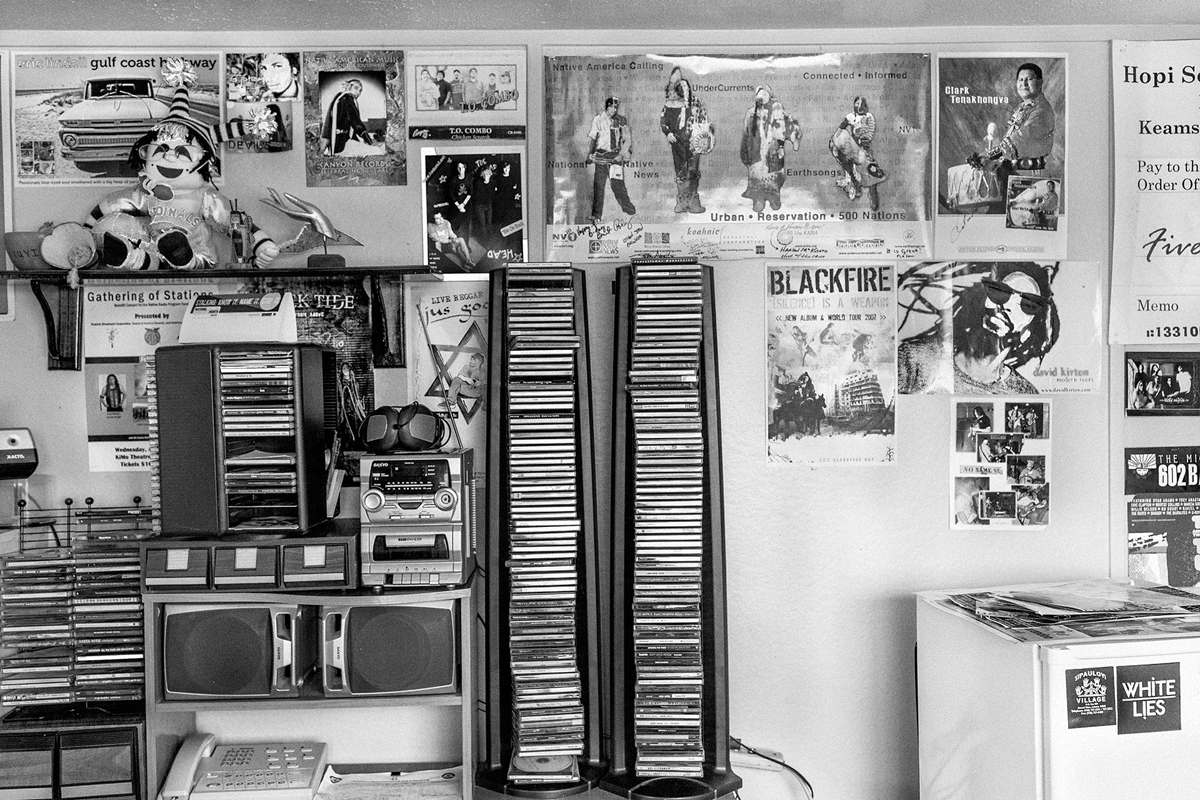

Slideshow: Inside KUYI

According to a 2012 Federal Communications Commission report, “Community-oriented and truly effective deployment of communications technologies within Indian Country has the potential to level the negative social, cultural and economic impacts that history has caused Tribal Nations and Native communities to endure.”

Anecdotal evidence suggests that only 10 percent of Indian Country has access to broadband Internet service. For example, on the Navajo Nation — an area about the size of Ireland — only about 20 percent of the population has access to broadband or 4G cellphone services, making technology like radio vital to tribal members.

“Native radio is growing, and until the broadband landscape changes in Indian Country, terrestrial radio stations are still very necessary to our communications needs,” said Loris Taylor, CEO of Native Public Media (NPM) “There’s a lot of darkness across Indian Country that we are trying to overcome.”

“Tribal stations are unique voices in the diversity and localism landscape of the radio dial,” said Geoffrey Blackwell of the FCC’s Native Affairs and Policy. “New radio licensing provides Tribal Nations the ability to preserve and advance their languages and cultural values through a communications medium, to increase economic development opportunities through advertising and promotion, to provide job training and employment and to promote the further adoption of new technologies, such as broadband.”

In places like Alaska, geographic isolation makes radio stations essential to linking communities while providing an outlet to the public’s needs.

“We are the only radio station in about 94,000 square miles,” said Jeff Seifert, station manager for KBRW in Barrow, Alaska. “So we have a lot of folks listening to us for all sorts of reasons — for news, weather, sports, you name it.”

Barrow is the northernmost city in North America and lies about 1,300 miles south of the North Pole. The town is the hub for seven villages — Anaktuvuk Pass, Atqasuk, Kaktovic, Nuiqsut, Point Hope, Point Lay and Wainwright — and is home to the Iñupiat people.

“Compared to other radio stations I’ve worked at, this is a very spiritual area — a lot of religious programming that you wouldn’t find on other public radio stations,” said Seifert. “We have a lot of programming in the religious vein that’s in both the English and Iñupiat language, a lot of song singing and translation of anything English into Iñupiat.”

“If you look at the history of Native Americans, there were huge efforts — not just by the federal government but by other parties — in trying to do away with tribal identities through the prohibition of having native youth speak their own tribal languages,” said Taylor. “So what I see radio stations really symbolize is freedom to reclaim our identity, to speak our language on the airwaves and the power of having our voices be heard in our ancestral language.”

A voice between the bands

Many radio stations broadcast in areas that are underserved by broadband Internet access, shown below in yellow. Hover over stations in blue for more about the tribes served and click listen to live broadcasts where available.

- Continental. U.S.

- Alaska

Currently 53 Native stations are broadcasting across the country, and it’s estimated that 92 percent of tribal radio stations create local programing, 75 percent produce hyperlocal news and 70 percent air tribal programming. According to NPM, 57 percent of stations are broadcasting in their local tribal language.

“We’re trying to work harder to get more language in, but it’s been a challenge because there are so few speakers,” said Margaret Rousu, general manager for Niijii Radio on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota. “Language is incorporated in a few different ways in the station, and we’re actually working to incorporate it more because we feel, as a native station, we don’t have enough right now.”

Listen to Niijii radio by clicking on the play buttons below.

Chickadee Story Mud Lake BulletinSource: KKWE Niijii Broadcasting

Currently, Niijii Radio broadcasts programs like Dibaajimowin — which is an Ojibwe word that means “telling stories” or “to tell something” and which explores the history of the community, plays stories in Ojibwe and facilitates translation from English to Ojibwe. The station is looking to create more programming in Ojibwe and is working with the local Head Start program to bolster language proficiency in the community.

“I want to say we have maybe four speakers on our reservation who are fluent, and the other speakers that we have, they are still learning,” said Rousu. “We know we haven’t gotten to the point where we need to be on that yet.”

Despite the role tribal stations play when it comes to being a first responder for isolated communities or strengthening tribal languages and cultural values, keeping the lights on is always a struggle.

Over half of tribal stations operate on annual budgets of about $200,000, and NPM estimates that about 20 percent of those stations work with closer to $100,000 a year to run.

Of 53 tribal radio stations currently broadcasting, 35 rely on funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. In 2014 that translated to about $4.5 million among 35 stations.

“And this was after a 5 percent decrease in funding during the federal sequestration,” said NPM’s Taylor, who added that it would probably be the same amount of funding in 2016, though it was hard to tell because of ongoing debates over the federal budget.

“We’re not just looking at sequestration. We’re looking at a budget deficit,” she said. “We know that there are continuing talks about how to address the budget in its entirety, so we’re quite frankly hoping that the funding will remain constant for these stations.”

With previous and possible future cutbacks, tribal stations continue to find other ways to pay the bills, like underwriting and pledge drives. However, the next few years are crucial for stations like KUYI on the Hopi Reservation, where the digital divide continues to divorce tribal members from relevant information in their own communities as well as the mainstream culture.

From KUYI’s 20-year-old faux-wood-paneled double-wide trailer, DJ AG — otherwise known as Aldric George — adjusted a microphone and cued a CD. Off air, George works as the Hotevilla youth and elderly coordinator. He also participates during the Hopi cultural and ceremonial calendar.

George took a breath, adjusted his audio levels and opened his microphone to broadcast the community calendar in both Hopi and English: The Hopi veterinary service has reopened. A country-western dance is just around the corner. There’s been a small change to the community health transportation program’s schedule.

Then George hit “play” on his CD and a Native American Church song went out — the shaking of a rattle, the gentle pounding of a drum.

“The community would survive without us, but it would be put in danger,” said Richard Davis. “We’re doing revolutionary work here. Every day that the tower is lit and the language is going on air is another day where the extirpation of a culture isn’t occurring.” ◆