By Dave Mayers for Al Jazeera America

3D illustrations by Dave Mayers for Al Jazeera America

Graphics and production by Joanna S. Kao, Lam Thuy Vo

Edited by Lam Thuy Vo, Victor Balta, Rhyne Piggott

Published on Jan. 30, 2014

This year's Super Bowl is expected to rake in $210 million in spending from the National Football League (NFL), businesses, visitors and media, which is a considerable cash injection into a local economy. But building a stadium to host the event is not always cheap and while private-public partnerships are supposed to relieve the financial burden, cities don't always get the best deal.

Below is a compilation of newest stadiums that hosted the Super Bowl in the past 10 years. Many of them were built in part to attract a championship game to a city. There are longterm economic benefits to having a large stadium in a city, but they are much harder to measure. While some teams threaten to leave town if a new stadium isn't built, it is nearly impossible to predict whether such threats would be fulfilled. It is also difficult to say whether touring musicians and other events would skip a city altogether because it has an old stadium (the many acts that continue to visit the O.co Coliseum and Oracle Arena in Oakland, Calif. — among the oldest pro sports venues in the country — suggest they wouldn't).

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

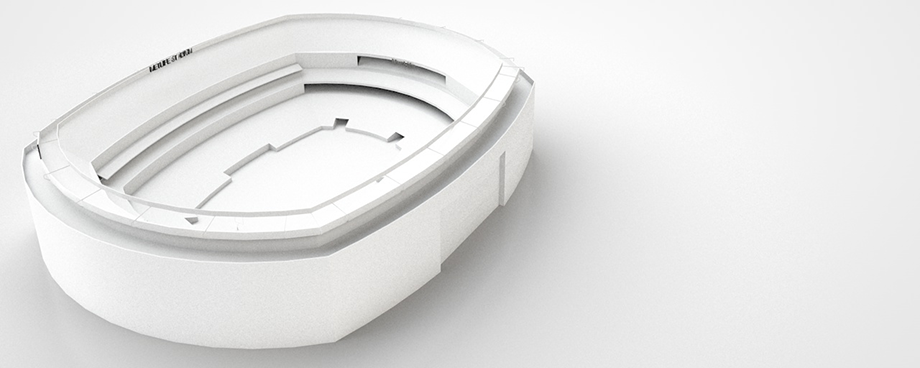

Currently the most expensive facility in the league and the home to this year’s Super Bowl, the $1.6 billion MetLife stadium is actually a fallback plan. After then-New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s vision of a largely publicly financed football stadium on the west side of Manhattan fizzled, the Jets struck up a partnership with the Giants to build a new stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey to replace the aging Giants Stadium.

Opened two years ago, the new MetLife Stadium is set to host the first outdoor, northern Super Bowl ever. While contingency plans for bad weather have been made, local politicians are playing up the economic benefits the championship game will have. A now widely discredited, NFL-commissioned estimate put the potential impact in the region at between $550 to $600 million. The study itself was never released to the public, but the large numbers continue to be quoted.

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

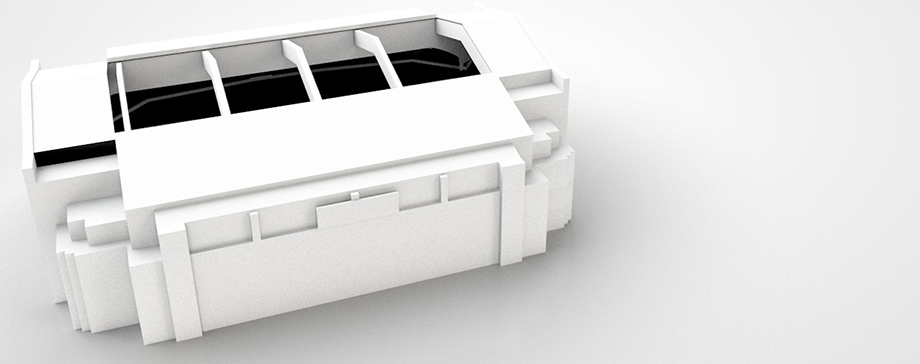

The small-market Indianapolis Colts have one of the most expensive stadiums in the NFL. The public share of the construction costs of Lucas Oil Stadium is significantly higher than other stadiums with similar price tags. Indianapolis is a sports obsessed city where voters are willing to foot four-fifths of the $749 million (2010) bill for a new, state-of-the-art stadium.

City officials were awarded Super Bowl XLVI four years after its construction. The venue has also hosted 2010 NCAA men’s Final Four and will be home to this year’s Big Ten Football Championship.

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

The pride of the NFL, the recently renamed AT&T Stadium -- still known colloquially as Cowboys Stadium -- was the first of the billion dollar football venues to open its doors. The new facility made headlines with some of the largest video screens in the world -- screens so big it was feared they would get in the way of the occasional high-flying punt.

The Cowboys are arguably the league’s most iconic franchise, and it’s nearly impossible to imagine the team leaving the city for a newer stadium elsewhere. In larger markets, local and state governments have more bargaining power with the league and will often get better deals on stadium construction. While Cowboys owner Jerry Jones covered most of the costs of the new stadium in Dallas, the public still made large contributions in the form of land, infrastructure and property tax exemptions given to the team.

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

One of first of the latest generation of sport facilities to host a Super Bowl, Raymond James Stadium includes 12,000 club seats and a massive pirate ship that fires its eight canons whenever the hometown Buccaneers score. Raymond James has hosted two Super Bowls (XXXV and XLIII) in the 16 years it’s been open.

The stadium was funded by a combination of a half cent sales tax increase, a tourist development tax and a state sales tax rebate.

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

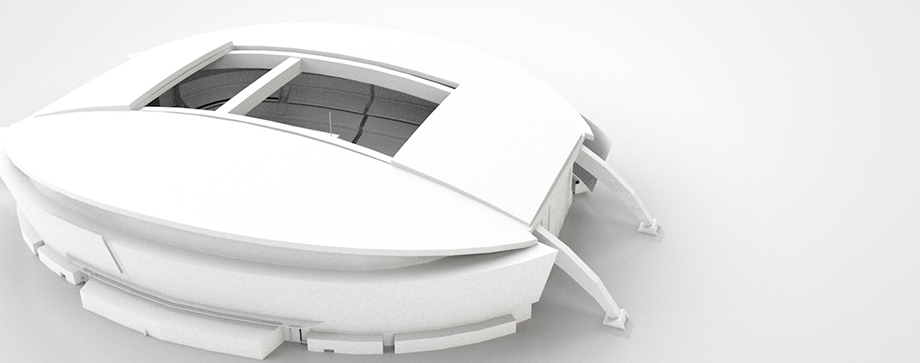

Built on a 165-acre plot of land in Glendale, Ariz., just north of Phoenix, University of Phoenix Stadium is one of the crown jewels of the NFL. Its designers boast that it is the first sports facility in North America to have both a retractable roof and a removable grass field. Giant fabric panels can close during the hottest parts of of August and September allowing the Cardinals to have early season home games. A 12‐million‐pound tray transports the natural grass field out into the desert sun on off days.

Two years after construction, Arizona played host to Super Bowl XLII. By its own estimate, Glendale lost $2 million throwing the 2008 game. With this in mind, last month the city asked for state assistance with funding for the next year’s Super Bowl, the second in Glendale in six years.

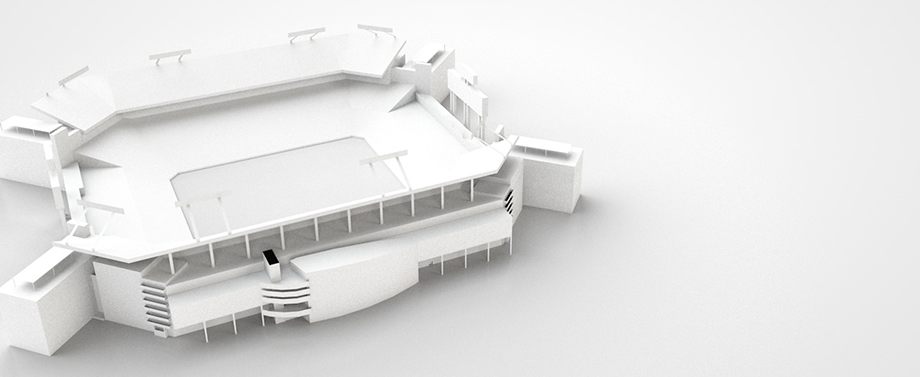

In 1996 more than two-thirds of Wayne County voters approved the building of a new football stadium for the Detroit Lions. The field moved the Lions back to downtown for the first time in almost 40 years. Ford Field was proposed as the linchpin in a revitalization project for downtown Detroit; the building’s design even features a Motor City mainstay -- repurposed abandoned warehouse. Ground was broken in 1999, Ford Field hosted its first game in 2002 and Super Bowl XL in 2006.

Detroit was awarded the Super Bowl despite the fact that it would be the first championship played in a cold-weather city in more than a decade. Although the game was played under a glass roof, the prospect of snow was still on the minds of fans and organizers looking to avoid gameday delays. The game went off without a hitch, but Detroit only took in an estimated one-sixth to one-third of the projected $300 million that the Super Bowl XL Host Committee claimed it would generate. More than a decade after it opened, Ford Field has yet to turn around the prospects of downtown Detroit.

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

Houston’s Reliant Stadium's website boasts that the building “is the only rodeo and NFL indoor/outdoor retractable roof” facility in existence. Reliant was the cornerstone of an effort to lure both a new NFL franchise and a Super Bowl to the city. A mere two years after opening, Houston played host to Super Bowl XXXVIII in 2004.

Not only were construction costs underreported, but it turns out, the city’s ability to pay for the stadium was overestimated. Like many cities, Houston increased taxes associated with local tourism to help pay the public share of the debt — hotels, motels and car rental companies would bear most of the new burden. Tourism taxes are an easier sell to local voters who are more willing to tax visitors than residents. When in 2009 tourism fell victim to the recession, the city had trouble servicing its debt for its NFL, NBA and MLB facilities, leading to a lowered bond rating the following year.

*Note: Many costs aren't accounted for in official figures. In her book Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities, Judith Grant Long takes into account the cost of land, infrastructure, operating income and expenses, and forgone property taxes when calculating her cost estimates.

Sources: Public-Private Partnerships for Major League Sports Facilities by Judith Grant Long, PcW, Google Earth, Al Jazeera reporting