The Rat Tribe of Beijing

Under the streets, a hidden warren of rooms for the thrifty

By Ian Johnson

Photos by Sim Chi Yin / VII for Al Jazeera America

Produced by Alex Newman

Edited by Jayati Vora, Mark Rykoff

Jing Ranming, 18, an actor and performer from Liaoning, sits in his room in an underground residence in Beijing, above.

Published on Saturday, Jan. 24, 2015

Reporting for this project was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting. The video is courtesy of Creative Time Reports.

BEIJING — Every morning, a metamorphosis takes place below the ground of China’s capital. In a world without sun or fresh air, people roll out of bed in windowless rooms, empty bedpans into communal toilets, pay 50 cents for a five-minute shower, ascend concrete stairways to the outside world and transform themselves from residents of the city’s most despised housing to strivers, hungry for a piece of the Chinese dream.

These new Beijingers, who number about 1 million, are known as members of the “rat tribe,” or shuzu, because they make their homes underground in warrens of small, often-dank rooms that are cheaper than almost anything they can find above ground. Most of the units are technically illegal because the government has decreed that basements and former air-raid bunkers shouldn’t be rented out, but like many things in China, they occupy a gray area. A huge market exists for the basement dwellings — roughly half the price of comparable units above ground — which often causes local officials to turn a blind eye.

Most of the residents are young arrivals, hoping for a foothold in China’s most important city, the center not just of politics, but of art, business and alternative lifestyles. They are actors and street sweepers, hair stylists and shampoo girls, newlyweds and in-laws, Buddhists and Christians. Many have dramatic, sometimes-picaresque stories, like the rags-to-riches one of Wei Kuan, a 27-year-old petty criminal turned insurance salesman — with career stops along the way as delivery boy, funeral singer, foot masseur and bathhouse worker.

“I am doing well because I’m scared of being poor,” Wei says in his apartment, a roughly 300-square-foot room he shares with up to nine other men. “Many of my colleagues live above ground, but I think it’s too comfortable; this place forces me to work harder.” Still, Wei, who now makes up to 30,000 yuan (about $4,800; 1 yuan = $0.16) a month — a drastic improvement from his initial monthly salary of 800 yuan — says he plans to move out by the Chinese New Year, in February.

These below-ground rooms owe their existence to two historical events. One is the Cold War, when Mao’s China struggled with the Soviet Union for ideological supremacy in the East bloc. In 1969, the same year the two countries fought a bloody border war along the Amur River, Mao ordered people to “dig tunnels deep” as protection against Soviet air raids. In Beijing, 300,000 people took part in the campaign, digging an estimated 20,000 underground bomb shelters.

A few years later, however, Mao was dead and his hardline ideology overturned in favor of the economics-first pragmatism of Deng Xiaoping. The shelters were commercialized, and the government’s Office of Civil Defense instructed that they had to turn a profit. By the 1980s, according to a memoir of a senior official in charge of the project, Beijing had 800 underground hostels, as well as underground supermarkets, cinemas and roller-skating rinks. In 1996, the government formalized this shift, passing a law mandating that new buildings contain underground civil-defense shelters, but that they have an economic use as well. This led to the proliferation of for-profit underground housing. Over the years, government agencies contracted out the spaces to private managers, who run them for a profit.

Meet the members of the rat tribe

Mu Huayin, 62, cleaner and caretaker of two basement residences in Beijing.

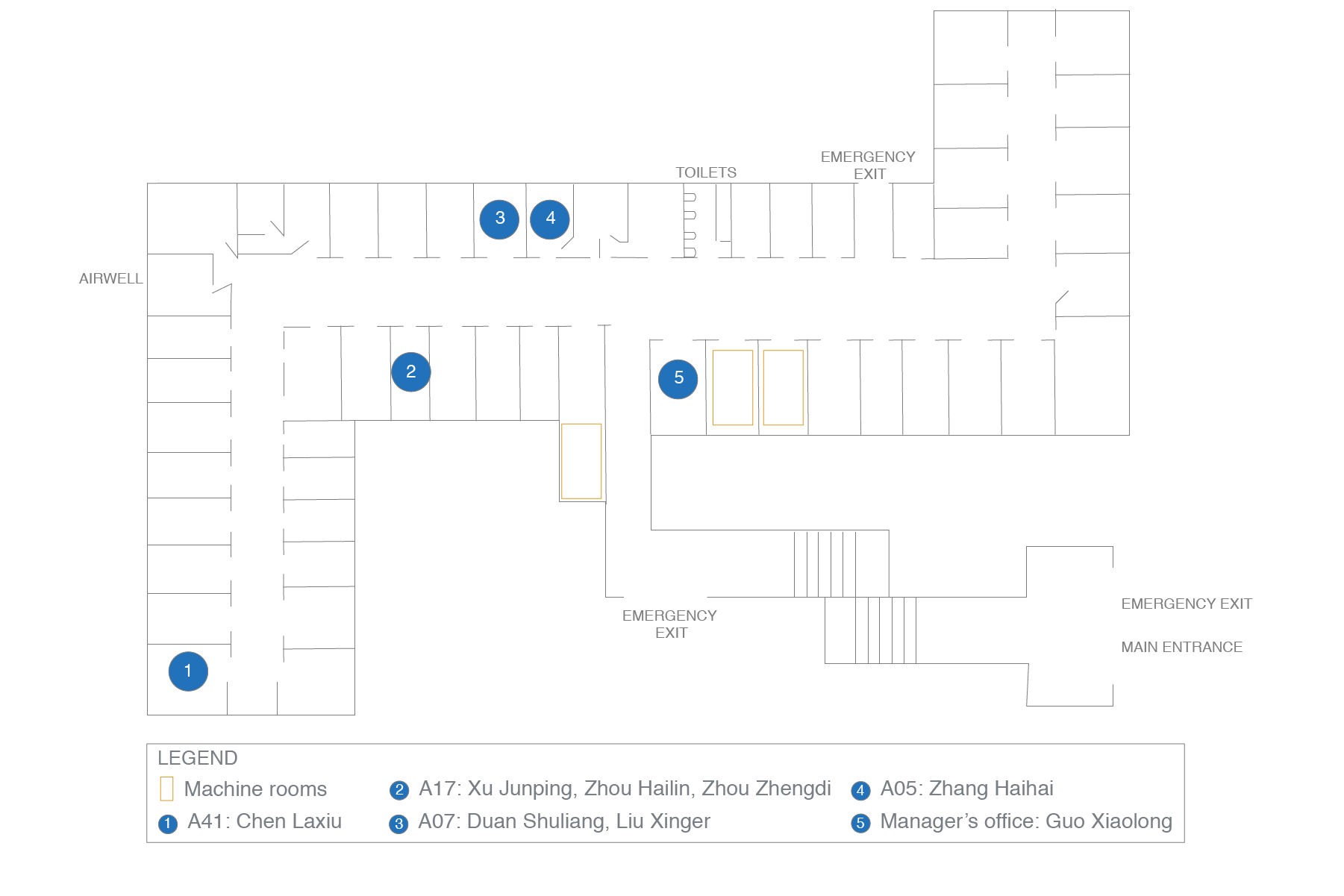

An underground residence in East Beijing

Beijing is the center of underground housing partly because of its geography, located as it is near the deserts of northern China. Except for a few humid summer months, it is extremely arid, making underground living similar to traditional cave dwellings in neighboring mountain areas — cool in summer, warm in winter and much quieter than living in noisy units above ground.

The second key event was urbanization, which caused major Chinese cities to explode in size. From 9 million in 1995, Beijing’s population grew to an estimated 21 million in 2013, 8 million of whom are migrants. That increased the demand for cheap housing, especially because many migrants aren’t legally allowed to settle in big cities. This is because they lack an urban household registration or urban hukou, which regulates where people are allowed to live. Without one, they aren’t allowed to apply for low-income housing, local schooling or other forms of welfare. Knowing they will never settle in Beijing, they often opt for cheaper accommodation.

Lower-cost housing exists in Beijing but mostly in the far-off suburbs or in dormlike conditions with six to 10 people sharing a room. Underground, most people rent out individual rooms of about 40 to 100 square feet for roughly 400 yuan a month. These prices are approximately half of those for comparable above-ground units. That allows migrants an affordable living inside the city’s urban core, making it easier to get to work.

“Of course, no one would prefer to live underground, but there was a strong preference to location,” says Annette Kim, a professor at the University of Southern California who surveyed 3,400 underground apartments with Lu Bin, a professor at Peking University. “What happens in most parts of the world is affordable-housing projects are in bad areas far from the city because that’s where land is affordable. But people don’t want to live there too because the commute is so far.”

Despite these advantages, the stigma of living below ground is strong. Some migrants say they haven’t told family members or delayed doing so for months. “When my father came to visit me he cried when he saw where I lived,” says Zhang Xi, an aspiring actor. “He said, ‘Son, this won’t do.’”

Zhang Xi: The actor from Mongolia who dreams big

Strict rules and regulations reinforce the sense of exclusion. Some basements have signs telling residents not to air out their bedding above ground, or even to sun themselves outside.

Given the growing density of cities worldwide, Kim says she sees Beijing’s underground cities not as a relic of the Cold War but as a possible precursor for urban living in densely populated Asian cities.

Officials, though, have mixed feelings about underground living. Over the past two years, Beijing municipal authorities have issued contradictory messages. In 2011, they said the use of air-raid shelters as housing would cease by 2012, citing safety hazards, such as the risk of fire or flooding. Another key reason seems to be that it goes against Beijing’s image as a modern city.

“We never allowed residential use of air-raid shelters,” says Xu Jinbao, office director of the Beijing Municipal Civil Defense Office. “But as time went by Beijing became so populous that people started to cram in underground.”

But the converted shelters and other subterranean rooms are tolerated as a pragmatic solution to the city’s crisis in affordable housing. “They have torn down some shelters, but there are so many and such a demand that I don’t see it being eliminated in the near future,” says Li Junfu, a sociologist at the Beijing University of Technology, who studies underground housing.

Another reason they are likely to stay is that underground hostel operators have legally binding contracts. Many operators were themselves migrants, pouring in life savings to install closed-circuit television, meet fire-safety requirements and partition rooms. Earlier attempts to close some of them down led to public protests, a rare occurrence in China.

Li estimates that about 5 percent of Beijingers live underground, a figure that Kim also believes is accurate, though less than some Chinese media report. Li says that what struck him is how so many of the people living underground are doing so not out of despair, but as a calculated sacrifice for the future. “I found a lot of people still hope one day to buy a house, or at least to live above ground,” Li says. “They have a positive spirit.”

This multimedia presentation is the result of a five-year survey of underground housing by the photographer Sim Chi Yin, who made portraits of more than 100 basement dwellers. Most are at the lower end of the economic spectrum, even though some have romantic dreams of making it big. Below are some of their stories, a cross section of the hopes and realities of trying to make it in Beijing.

"Farming is hard work," she says while sitting on her tiny bed in room 1 on the map. "You work in the fields and then you're still not free, because you have all these other chores to do. Here, I work my hours and then I'm off."

Chen and her husband found jobs cleaning subway stops on the same line — the new Line 6, which runs east-west through the center of town. She keeps the Dongdaqiao stop clean and he works the Hujialou one. Their basement dwelling is a few stops farther east, near the Fourth Ring Road.

"Of course our home back in Guizhou is much better. There's no comparison," she says, laughing at the thought. "We have a courtyard and six bedrooms. Here we just have four square meters. But we don't plan to stay here forever. It's a safe place to sleep at night and watch some television serials off a disk."

But the unit has become something more. It's part of one of the warmest, friendliest underground housing compounds in the city, run by Guo Xiaolong (see below). Chen's son found the room for them; his fiancée's parents live a few doors down.

The gregarious Chen often visits with them, even though she usually can't understand their thick Shanxi accents. Other times, she's out window-shopping — but never spending money. She thinks she can save half her salary and plans to spend it on her son's wedding and her retirement.

In a way, coming to Beijing and living in an old air-raid shelter is a second spring for her. It is a chance to earn some money and to see new things. Back in Guizhou, it was impossible for people of her age to find jobs. Although only middle-aged, they were considered old and she says people laughed at her when she tried to work. "In our hometown people would laugh and say, ‘You have three sons and if each of them gives you 100 yuan, that would be enough. Why do you need to work?' But in Beijing we can find work."

Read more

Zhang's mother walked out 10 years ago. Despite scrimping and saving, his father, the only breadwinner, couldn't afford to put his son through years of college. So in 2013 the 22-year-old dropped out and came to Beijing to learn how to be a makeup artist.

"I don't try to hide the fact that I am living in a basement. My friends all know. Actually, initially I posted these pictures of me with the celebrities I did makeup for online. My schoolmates saw them and got very envious. They thought I was having a wild time in Beijing, running from hotel to hotel. Actually, I was running from hotel to hotel, but coming home to a basement room at night."

A year and a half after coming to Beijing, Zhang is thinking of leaving, citing the overcrowding and the cuisine. "My plan now is to quickly finish the makeup course and go back to Wuhan. There's nothing really keeping me here."

The basement isn't the problem, though. "Sometimes I come home alone to my basement's room and I quietly think about things. Just being in a small space by oneself makes one quiet down. It's a space where no one disturbs you. I'm used to not seeing the sun already."

Read more

For the past three years, though, he has supported himself through a variety of jobs: food-delivery boy, courier, waiter, supermarket cashier, shoe peddler. He took the basement room to save money, he says, only paying 500 to 600 yuan a month: "I was pragmatic about it."

But at times the basements can be fetid and dank — especially in the summer. "I leave the towel on my bed headboard and overnight it grows mold: green, blue, white, spotty ones."

Though Li says he accepts the "rat-tribe" label, because it's an accurate description, he "wouldn't say I look down on the people who live in basements … I don't feel there's anything pitiful about my situation. I have a room, a bed, and once I'm lying under the blanket, what's the difference between me and other people?"

Read more

His childhood dream, however, was to become an athlete or at least a physical-education teacher. Though that didn't work out, he still often wears Adidas sports apparel. Now, he is employed at a former bomb shelter in Beijing's eastern suburbs that's been converted into an underground apartment complex. There, he cleans the public areas and repairs locks and doors and cables. He spends much of his leisure time in a little room near the entrance, monitoring four closed-circuit monitors — a requirement by authorities to discourage thieves.

Guo is a man of few words, but he runs a tight ship and the basement is a friendly place. Guo often greets his tenants after a long day, and quickly fixes small problems they have. Since his parents died four years ago, he has no permanent home, Guo says, except the basement. "Once one's mother is no longer around, one has no home. But if basement people are ‘rats,' then I am the king of the rats!"

Read more

He is 18 and she has just a few more years to earn the cash, says the 43-year-old from Harbin, who shares this dormitory room with a female co-worker.

"According to the customs in our village, we need 200,000 RMB [yuan] in cash, at least three pieces of gold for the bride to wear on her body. Only then can we get a good bride. In a few years' time I will have made enough money working here, and my son can then get married. Right now I still haven't earned much. I make just 3,000 yuan a month."

But she does not see it as a sacrifice being in Beijing, working alone, leaving her husband, daughter and son at home to farm corn on a third of an acre of land.

"I don't like to farm!" she says. "I'd rather be a migrant worker. To farm I must work under the sun, get so dirty. These days who would rather be a farmer?"

Read more

These days, the 18-year-old, who lives with his girlfriend in this 500-yuan-a-month basement room, feels better about life. He left his first job in a factory making electric sockets to cook noodles and dumplings in a restaurant in Beijing South Railway Station. He likes the peacefulness of the basement, he says. "I can sleep pretty well because it's quiet here."

Chang parties as hard as he works, going out for meals with friends or going to sing his heart out at KTV parlors. Sometimes, he also goes to Tiananmen Square to take photos to "show off to friends back home."

"I show people back home: ‘Look, I'm in the capital city.' People there think it's great to be in the capital. But my dad just tells me to be careful and don't get into trouble."

Read more

"I'm so used to life in Beijing I don't want to go home! When we're out here, if we're hungry we just get something to eat. There are not so many complicated things. Living in the village, it means helping out with this family and that neighbor's family. We're busy all day, doing this and that. Now, I'm used to the peace and quiet here."

Xu, who has been a live-in nanny and domestic worker for most of her time in the capital, initially rented rooms in basements near her workplaces on her rest days, to sleep or just have her own space.

Since November, she has been living in this room (number 2 on the map) in east Beijing, sharing it with her 17-year-old son, Zhou Zhengdi, who had dropped out of school back home but is learning to repair computers in Beijing's high-tech district. Her older son works in Nanjing.

Xu's husband, Zhou Hailin, 48, is a security guard working and living at a bathhouse in another part of Beijing. He comes to visit occasionally, bringing food from a street stall. When he visits, the three of them share the double bed.

Xu says with a laugh: "We squeeze in and sleep here, feet to face — two people's heads face that way and one person's head faces this way. That's the only way we can sleep. If three of us faced the same way, it would be impossible. Good thing we're all not fat!"

Read more

This is the second time he has been to Beijing from his home in Henan province. His parents are peanut-and-corn farmers with a decent two acres of land. Liu has helped his parents with farmwork since he could walk, but when he was in high school he fell in love with documentary cinema and the realistic films of China's master filmmaker, Jia Zhangke.

"In 2006, he won a big prize in film. I saw in news and I thought if I had an opportunity to do film I will, and if not I will be a photographer. I can go back to Henan and open a studio doing weddings, commercial, advertising work."

But his true goals are loftier. He loves to read China's Nobel laureate Mo Yan, as well as Yu Hua, Faulkner and Tolstoy. Their books sit in a pile near his bed in the basement room.

"My generation is so different from my parents'. People of my generation are civil servants, car salesmen. No one farms anymore. And factories are coming closer and closer to our farmland, making food, instant noodles, toilet paper.

"My parents' generation lived on and depended on the land. But we have all left the land.

"Dad wanted me to be a primary-school teacher. But I thought art teachers' [salaries were] too low and they had too much free time. So I wanted to do something more."

"I learned of basement living from Jia Zhangke's film "The World," where there's a character who lives in a basement. The first basement I stayed in in Beijing was large but very humid, 700 yuan per month. After one month it was still smelly and there was water on the floor from the humidity and things got moldy. So I moved. Then I found this room. It's about eight square meters for 360 a month. I have no income, so I live here. It's OK. I do feel uncomfortable here, though. I feel a sense of fatigue. Maybe because there's no sunlight here.

"Humanity is too scary. Think about it: There's not even enough space to house us anymore above ground. We are now living underground ... There's the subway, car parks and basement homes — all underground. Is this city hollow underneath?"

On his laptop, Liu writes down his thought. On one page he writes:

The rooms upon rooms, the intricate corridors, all of it brings you a little bit closer to the direction you want to take, as you keep walking forward. At night, you can lose your way and you can't find your own unit, but each day you continue to go above and below ground, above and below ground, above and below ground.

Read more

An earlier version of this story incorrectly spelled Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke's name.