In Bangladesh, the sham of Shams factory

Mega-chain the Children’s Place continues to source clothes in unsafe sweatshops

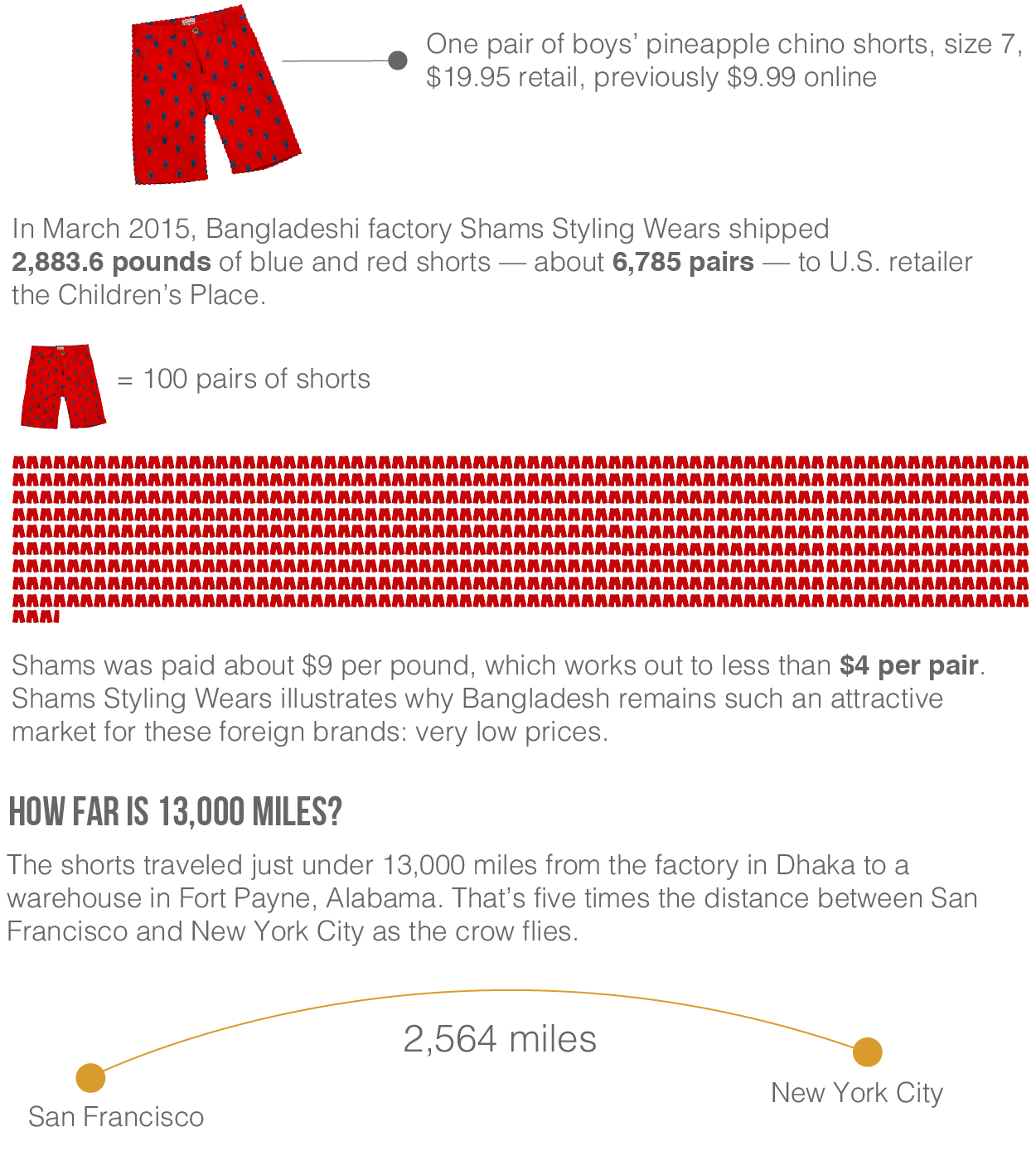

On March 2, 135 large cardboard boxes arrived at the Port of Savannah, in the U.S. state of Georgia. They were packed with hundreds of pairs of shorts in two patterns and delivered to the warehouses of the largest kids’-clothing-only retailer in the United States, the Children’s Place. The first pattern featured blue pineapples on red cotton twill and the second, red palm trees on a dark blue background. Both styles were a bargain, just $19.95 at retail and, after discount, well under half that on TCP’s website at the time of writing. Belying their carefree design, the mini surfer dude shorts came from a cheerless factory in a landlocked city in a country half a world away — Shams Styling Wears, located on the outskirts of Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka.

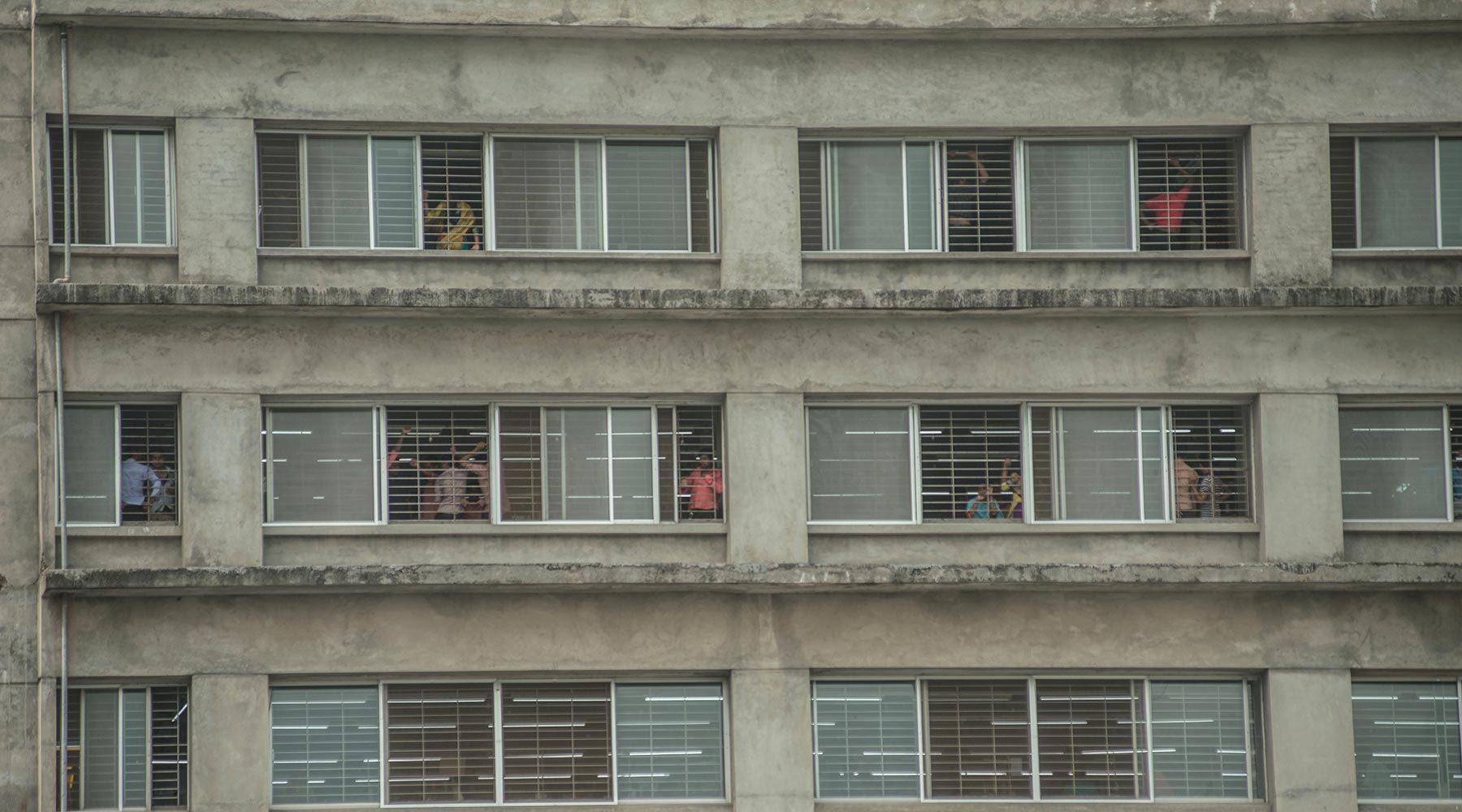

Shams occupies a drab nine-story concrete tower in Savar, a polluted industrial suburb. The structure is less than five miles from Rana Plaza, the eight-story garment factory building that collapsed on April 24, 2013, killing more than 1,100 workers and injuring at least twice as many. The disaster was supposed to mark a turning point in the manufacturing of ready-made garments, the largest industry in Bangladesh. In the aftermath, multinational brands launched two major initiatives to improve the structural, fire and electrical safety of their Bangladeshi factories. In May of that year, a European-led consortium that included the brands Primark and H&M launched the legally binding Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. The agreement created a system of inspections that would warn, punish and eventually disqualify factories that didn’t meet basic safety benchmarks.

The Children’s Place, however, joined other American brands like Walmart in forming the far less strict Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which relies on third-party inspectors to identify key deficiencies but imposes no real deadlines in implementing changes. Similarly, the accord mandates that foreign brands must finance improvements to bring their Bangladeshi factories in line with international standards, but the alliance doesn't.

“The two competing initiatives [show] the tension between civil society wanting reform and the brands that want control over the initiatives they join,” says Heather White, a supply-chain expert who founded the labor monitoring nonprofit Verité. “The U.S.-led initiative operates by excluding trade unions, which leads to reduced, shoddy standards, limited improvements, a huge waste of NGOs’ time and an erosion of credibility.” The alliance doesn’t formally engage with organized labor in the same way as the accord, which has three labor representatives on its board, does. This a serious concern in Bangladesh, where the outspoken organizer Aminul Islam was tortured and murdered in 2012, allegedly at the hands of the country’s Industrial Police force.

White is more optimistic about the European consortium — as long as unions remain involved.

Javed Ali, a 21-year-old worker on the factory floor at Shams, asked that his real name not be used for fear of losing his job. He says that although the workers have a union, “it is a puppet trade union. The management put their own people on it, just to show the buyer that they have a trade union.”

More than two years after Rana Plaza, the Shams factory, like many other garment factories in Bangladesh, has no contingency plan should a fire break out. A June 2014 fire inspection by the Texas-based engineering firm CCRD, which was hired by the alliance, found aisles that were blocked by merchandise, and an alarm that wasn’t monitored by the local fire department. CCRD’s report suggested that these were serious issues and should be corrected within six months. But as of April 16, when Shams was reinspected, it had fixed fewer than half of the critical deficiencies, according to GMMB, the Washington, D.C.-based consultancy that handles public relations for the alliance. Eight of the nine highest-priority fire hazards have not been fixed. A representative from Shams told Al Jazeera America in June that it has completed “over 50 percent” of the necessary repairs, and the outstanding items will be completed “within a few months.”

This cavalier attitude shocks safety expert Keith Wrightson of the U.S. consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. “The plan of action should say, ‘Close all operations until the sprinklers are installed,’” he says. “They know what’s going to happen.” A similarly unsafe building on the outskirts of Dhaka, Dignity Textile Mills, burned down on May 31. No one was killed or injured. But the seven-story structure, which was empty, lacked a sprinkler system that could douse or slow down a fire — just as in Shams. The factory remains without sprinklers despite two inspections, in June 2014 and April 2015, which identified this as a safety hazard.

These conditions appear to violate the Children’s Place’s own supplier code, which requires factories to “provide workers with a safe and healthy workplace … ensuring at a minimum, a safe building with proper fire safety equipment; sanitary facilities with adequate lighting and ventilation.”

But Shams workers have more immediate concerns than structural or fire safety violations, which can seem abstract. “Sometimes we don’t get a single day off in a month,” says Ali. He is sitting in a bare, concrete room, just 13 feet by 13 feet, which he shares with three other workers from the factory. “And the most we get is two days off in a month.” They are also forced to do overtime, he adds, at least two hours a day. That means they end up working 10 or 11 hours per day and, most of the time, seven days per week.

Shams Styling Wears is one of more than 20 garment factories owned by the Standard Group. The conglomerate was founded as an engineering and construction company in 1969, before Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan. In the mid-1980s, Standard opened one of the first clothing factories in Dhaka. The group now dabbles in real estate, manufacturing and insurance. In an interview with Al Jazeera America, Standard Group cofounder Mosharraf Hussain, who portrays himself as a grandfatherly figure benevolently providing employment to more than 40,000 people, denies that his firm forces any employees to work overtime or put in seven-day workweeks. “No, never,” says Hussain, 71, at his well-appointed Dhaka headquarters. “It is not possible. … [We] have to go by norms now.” He adds that if some of the workers wish to pick up more money, they can do a few extra hours. “Maybe you are making some confusion,” he says. “This kind of thing may be in some other factories.”

More than five months after executives from the Children’s Place refused to meet with a Rana Plaza survivor and other activists at a rally at its headquarters on March 12, the U.S. company remains unwilling to fully address its record in Bangladesh. Emails and phone calls over a period of months requesting comment about what workers in Bangladesh describe as violations of TCP’s code of conduct went unanswered.

In the first six months of 2015, Shams has already sent more than 10 shipments to TCP in the United States and Canada — that’s 390,383.5 pounds of clothing. And Shams Styling Wears illustrates why Bangladesh remains such an attractive market for these foreign brands. Hussain explains that he and other Bangladeshi suppliers operate on thin margins. “Very low, maybe 3, 4, 5 percent,” he says. “It is a competitive market. … Who is putting [in] the lower price will get the order.” According to this reporter’s calculations, Shams was paid about $9 a pound for a container of shorts it recently shipped to the Children’s Place.

The garment company is able to survive on these narrow profit margins on the backs of its workers: Ali, the highest-paid of three Shams workers who agreed to speak to Al Jazeera America on condition of anonymity, makes only $52 per month in base pay and $122 with overtime. “We are not paid on time,” Ali says. “We should be paid between the third and fifth of each month. Usually, we get our basic salary on 10th, but have to wait for till the 15th or 20th for our overtime pay.” The overtime pay, he adds, is often short.

This means that while American moms can buy TCP’s red and blue twill shorts for the price of a couple of Happy Meals, Ali has to work for two days, with overtime, to afford a single pair.

We traced the route a pair of boys’ pineapple chino shorts took from the Shams Styling Wears factory on the outskirts of Dhaka, Bangladesh, to the Al Jazeera newsroom in New York City.

These low margins likely contribute to other kinds of apparent violations by Shams — and perhaps other suppliers — of TCP’s vendor code of conduct. And the alliance’s 2014 financial statement shows why the group may not be much help. Of the roughly $5.5 million the group spent, just $272,583 went to inspections. It spent slightly more than that on communications and public relations. There are line items for both worker support (roughly $472,000) and training (roughly $63,000). Of the total expenditure, 20 percent, or $1.1 million, was spent on expenses for the board. Another million went to legal fees.

The accusations from Shams workers aren’t the first time a Standard Group garment factory has faced scrutiny. In November 2013, a blaze consumed the 10-story Standard Garments building in nearby Gazipur. The circumstances remain unclear. The Standard narrative is that local workers unconnected to the factory, amped up by a false rumor that police had killed one of their colleagues, torched the building and 22 vans loaded with clothes. Another version suggests that workers from the Standard factory, protesting low salaries, were also involved in the arson.

A few days after the fire, on Dec. 3, 2013, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina came to the remains of the factory to show her support for Standard CEO Mosharraf Hussain and his colleagues at the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association. After Hasina toured the factory, she gave a press conference there with Hussain, a pink box of tissues strategically placed at arm’s reach. After the CEO broke down in tears, Hasina promised to follow up with the banks to help reopen the factory. According to a press release from Hasina’s ruling Awami League Party, the culprits of the fire were “evil elements…[belonging] to the anti-liberation force.” She told the crowd to remain vigilant. “We have information that they’re now hatching [a] conspiracy to sink ferry and steamer,” she said. It’s unclear what ferry and steamer she was referring to. Within a week, the government-owned Bangladesh Bank gave Standard Group $25 million in low-interest loans.

Standard Group also filed an insurance claim with Standard Insurance. (That company was later investigated on another matter and had its license suspended by Bangladesh’s Insurance Development & Regulatory Authority.) Though the insurance concern is an independent public company, three of Hussain’s children, his wife and two business partners from clothing ventures sit on its board.

Despite Bangladesh’s ongoing safety and compliance challenges, the country holds one powerful competitive advantage: It is still the cheapest place to source clothing. “The industry is there for all the obvious reasons,” says Pamela Ellsworth, who heads the Global Fashion Management program at New York's Fashion Institute of Technology. In its 2014 annual report, the Children’s Place agreed, saying it plans to manufacture even more clothes in countries such as Bangladesh. “In order to maintain and/or reduce the cost of our merchandise, we have reduced and will continue to reduce production in China and … move production into other developing countries.” The report estimates that 20 percent of these imports came from Bangladesh. Al Jazeera America’s analysis of TCP’s 2014 shipping records indicates that Bangladesh likely accounts for around 50 percent of the company’s imports.

But the Children’s Place also acknowledges the risk of making clothes in a country such as Bangladesh. “The failure of our third-party manufacturers to adhere to local law in the areas of worker safety (e.g. fire safety and building codes), worker rights of association, and social compliance and health and welfare requirements could result in accidents and practices,” its annual report states, “that cause disruptions or delays in production and/or substantial harm to our reputation.”

That’s not the only outcome of TCP’s suppliers violating local labor laws. Those colorful chino shorts that are available for a song in U.S. stores have proved costly for workers like Ali — and could prove deadly as well.

Editor's note: This article was updated to clarify that the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety doesn’t formally engage with unions in the same way that the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, which has three labor representatives on its board, does. The alliance, however, does have a board labor committee that advises it on labor issues; it has also conducted safety assessments at some factories with participation from the union registered there.