Pigeon Racing in South Africa

In this competition, there are no color lines

The truck drivers parked in dry scrub beside the highway, lit fires to ward off the evening cold and waited until dawn to release their cargo. They were a few hundred meters outside Hanover, a small town deep in South Africa’s Karoo semidesert. The trucks had traveled nearly 24 hours from Cape Town, tracing old apartheid patterns as they departed the city. The first truck circled the Cape Flats, a peripheral expanse of land, now wracked by poverty, where thousands of people were forcibly relocated from whites-only areas 50 years ago. The second skirted the lower edges of the formerly white southern suburbs, traversing the Cape Flats without stopping. The third made its way through the northern parts of the city, traditionally a white Afrikaner stronghold. Once the trucks had their cargo, the drivers began their 400-mile journey inland, half the distance from Cape Town to Johannesburg.

They were carrying a total of 15,912 pedigreed pigeons.

The day before, while waiting for the first truck to visit his pigeon club in Paarl, 40 miles from central Cape Town, Yusuf Moerat, 86, sat behind a low trestle table, selling chips, samosas and soft drinks. He wore a white fez and a checked blazer. He held his back upright, resting his hands in his lap. The hall was thrumming as fellow members, dressed in old jeans, peaked caps and worn jackets, arrived carrying birds in slatted wooden boxes, lining up to check them into the race. Moerat greeted the men warmly as they entered, shaking their hands and counting out change when they purchased snacks. His son and racing partner, Yazeed, was responsible for preparing the Moerat pigeons — training, feeding and dosing them with high-performance medication, an obsessive routine requiring hours of attention each week — and did all he could to ensure that the birds were in peak condition for the race.

The race, the Western Cape Classic, was the Moerats’ first opportunity to compete against pigeon fanciers from across the Western Cape, South Africa’s fourth-largest province and most fanatical pigeon-racing area. Undisputed champions in their organization, the Federated Board of Homing Unions (FBHU), the Moerats were for decades considered among the best pigeon racers in the region, but with no way of testing their birds against top performers from other clubs, this honor had always been contestable and subject to debate.

During ordinary pigeon races, the three large umbrella organizations in the province, including the FBHU, operate pigeon trucks independently, releasing their birds at different times. The Western Cape Classic was organized to streamline this process and bring fanciers together in a single event for the first time. “This event is important for the unity of this sport,” said Rick Engelbrecht, a member of the race organizing committee. “By working together, we can make pigeon racing stronger.”

Moerat, who has been named annual champion of the FBHU more times than anyone else and whose competitive instincts remain undimmed after more than 60 years in the sport, was considered a strong contender for the title. A pillar of the local pigeon racing community and a symbol of excellence in spite of adversity, a victory would cement his reputation as one of the very best.

“Many people could win this,” Moerat said, lifting his voice above the din of pigeons in the Paarl Pigeon Club hall. It was approaching 10 p.m., but he wasn’t tired yet. He would catch up on sleep the following day, while his pigeons were in transit to Hanover. “It’s the first time we’re up against guys from other areas. There are plenty of good pigeons in this race. But I know we have the birds to do the job.”

Pigeon racing has a long history in South Africa, passed on from European colonists during the 19th century. The sport was racially segregated until the end of apartheid, with separate clubs for white participants and those classified at the time as colored — people of mixed race or native Khoi descent. Starting in 1990 the laws that enforced this segregation were scrapped, and the sport gradually became more integrated. But more than 20 years later, despite outward unification, there remain ingrained divisions that keep local enthusiasts apart.

Fanciers, who must rank among the world’s most dedicated hobbyists, painstakingly train their birds to fly home from remote locations as quickly as possible, taking advantage of the birds’ homing instincts. Pigeons navigate using visual landmarks, the earth’s magnetic field and the positions of the stars and sun, among other cues. Domesticated in the Fertile Crescent more than 4,000 years ago, homing pigeons were once the fastest means of sending long-distance messages, eclipsed only by the invention of the electric telegraph in the early 19th century. (Reuters, the international news wire service, was founded in 1849 when Paul Reuter, a German entrepreneur, set up a pigeon carrier service to bridge a telegraphy gap between Germany and Belgium.) The sport of pigeon racing took off in Europe in the 1850s and has maintained a strong international following ever since.

Cape Town fanciers seldom articulate why they race pigeons, often claiming to have simply picked the habit up from family or friends, but the main attraction seems to be the deep personal satisfaction they derive from having their birds return home. “You treat your birds well, with love, and they want to come back,” explained Moerat.

To compete in traditional races, fanciers load their birds onto custom-built trailers, which are hitched to cargo trucks and, after being taken to a series of collection points, driven to liberation spots hundreds of miles away. Each pigeon flies home to its loft and is timed by its owners upon its return. The birds are ranked according to their average flight velocity — linear travel distance, as the pigeon flies, divided by time — as individuals from different lofts compete over unequal distances. In South Africa, flight velocities are expressed in meters per minute; a good average speed over a 400-mile race, depending on weather conditions, can translate to more than 60 miles per hour.

Many of the Western Cape’s pigeon racing clubs were established during apartheid. The FBHU, the largest umbrella organization in the country, was formed in 1953 to give fanciers excluded from whites-only clubs the chance to compete in their own events. With more than 500 members, it is the biggest pigeon racing organization in the country. In recent years, increasing numbers of white fanciers have joined, but the FBHU is still predominantly made up of fanciers classified as colored two generations ago.

Moerat was born in Paarl, the third-oldest town in the Western Cape, in 1928. He grew up around his father’s pigeons and by the age of 16 started winning competitions. As a young man, he kept a pigeon loft at his family home on Van Der Lingen Street, part of a small multiracial neighborhood near the middle of town. “We had white and brown neighbors,” he said. “People got along. You could walk next door to borrow sugar, that kind of thing.”

At the western end of the street was an Afrikaans cathedral. At the eastern end, on the banks of the Berg River, stood a small mosque. The mosque was built in the late 1890s, less than 300 meters from Paarl’s first mosque, which opened in 1889, half a century after the abolition of slavery, in 1834.

By the time Moerat was born, a number of local Muslim families were moderately prosperous. His father was a successful fruit and vegetable merchant, a career Moerat took up after finishing school. He was married at the age of 24 and fathered five children. He played rugby, tennis and cricket and spent as much time as possible with his birds. (In 2003 he was retroactively awarded national Springbok colors for rugby, which, like pigeon racing, was segregated during apartheid.) The National Party, which won the national elections in 1948, was busy drafting the laws that would define the apartheid system — but it would be another decade until the Moerats were uprooted and the neighborhood that they knew destroyed.

The Group Areas Act, passed in 1950, forbade the existence of racially mixed neighborhoods in South Africa, laying the foundations of spatial apartheid that persists in many places. Urban spaces rapidly began fragmenting as they were bent to fit the doctrine of separate racial development. Highways were built to buffer white suburbs from black ghettos. Nonwhite housing projects were built on the fringes of cities, far from businesses and services. In the heart of Cape Town, District 6, a historically diverse working-class neighborhood above the harbor, was razed between 1968 and 1982, ejecting some 60,000 colored residents to housing projects on the Cape Flats, which since their creation have been synonymous with gang violence, unemployment and social and economic marginalization.

Removals operated in both directions in Paarl, with white people being sent to live on the western banks of the Berg River. In 1968 the Moerats moved to a recently vacated house that had been owned by a white family, in the Charleston Hill neighborhood. For months afterward, Moerat returned to his old home with a basket, collecting pigeons that flew back. He stopped when the birds, having recalibrated their internal maps, learned to locate his new house.

“We were lucky,” he said. “We could afford to move to a decent area. A lot of families had to move further away. They got mixed up with all sorts of people — gangsters, alcoholics, thieves. It’s very hard to live like that.”

He lives in the same house today, sharing it with his wife, Rhoda, and Yazeed, his only son. Pigeon racing trophies crowd the shelves. Framed Quranic scripts adorn the walls. It is a comfortable, well-used space, not a wealthy one. The racing loft is in the backyard, where paint cans, old car tires, a broken bicycle and a discarded woodstove lean against the walls. The peeling two-story structure provides accomodation for more than 300 pigeons.

Moerat’s childhood home is 1.25 miles away as the pigeon flies and 2.5 miles by road. Paarl, like virtually all towns and cities in South Africa, still bears visible marks of apartheid spatial planning. According to census data, the western half of the town is wealthier and home to a far greater proportion of white people. East of Charleston Hill, in poorer neighborhoods like Chicago and New Orleans, street gangs peddle drugs and spray territorial markings across walls. At the bottom of Van Der Lingen Street, once the center of the local Muslim community, the small mosque stands in a vacant, weedy field beside the Berg River. Spared by the bulldozers that demolished homes, the mosque is bordered by a shopping center, a minibus taxi stand and the sports grounds of a prestigious girls’ school.

Scroll for more

At 7:15 a.m. on Saturday, Sept. 12, the pigeon trailers outside Hanover sprang open in unison, and with a great clap, nearly 16,000 birds burst into the air. They ascended in a twisting, bulging column, momentarily obscuring the orange sun, before circling to get their bearings and setting off on the 400-mile journey home. Feathers and straw fell as the birds departed and silence settled once again over the plain. A group of Afrikaans farmers stood next to their cars, craning their necks. “I’ve never seen anything like this,” said one, a Northern Cape pigeon fancier who was not competing in the race. He drove 60 miles to watch the release. “It’s spectacular.”

Achmat Ras, 41, drove through the night from Bonteheuwel, one of the more notorious gang neighborhoods on the Cape Flats. His 25-year-old half brother, Moegamat, and 16-year-old cousin, Raheem, went along. “They’ve been going crazy to watch this,” Achmat said. “They’re both new to this sport. Growing up on the Cape Flats is difficult, but pigeon racing opens your mind. You learn about biology. You see the world differently. You don’t have to become a gangster when you have this in your life.”

Achmat's father was waiting at home to clock their birds in. He grew up in Stellenbosch, near Paarl, before being evicted twice under the Group Areas Act, Achmat said. “He took his pigeons with him. In Bonteheuwel his new neighbors forced him to break the loft down. They thought it was a health risk. He gave his pigeons away. It broke his heart. I’ll never forgive them. But he started again, and here he is, still racing 30 years later.”

In Paarl, Yusuf and Yazeed Moerat walked outside after saying their midday prayers. They ascended the stairs of their wooden loft. The wind rose, dragging ragged clouds across the valley. Its southeasterly direction was bad news, since their birds would be fighting a headwind on the final stretch of the race. “What can you do?” Yazeed asked his father. The old man shrugged and settled into his chair to wait.

Their first bird home, a hen named Beauty, clocked in at 2:10 p.m., completing the race at an average velocity of 53 miles per hour. Both men knew right away that it wasn’t good enough. “The wind was against us,” said Moerat. “We have a better chance when it blows from the north. Ah, well.”

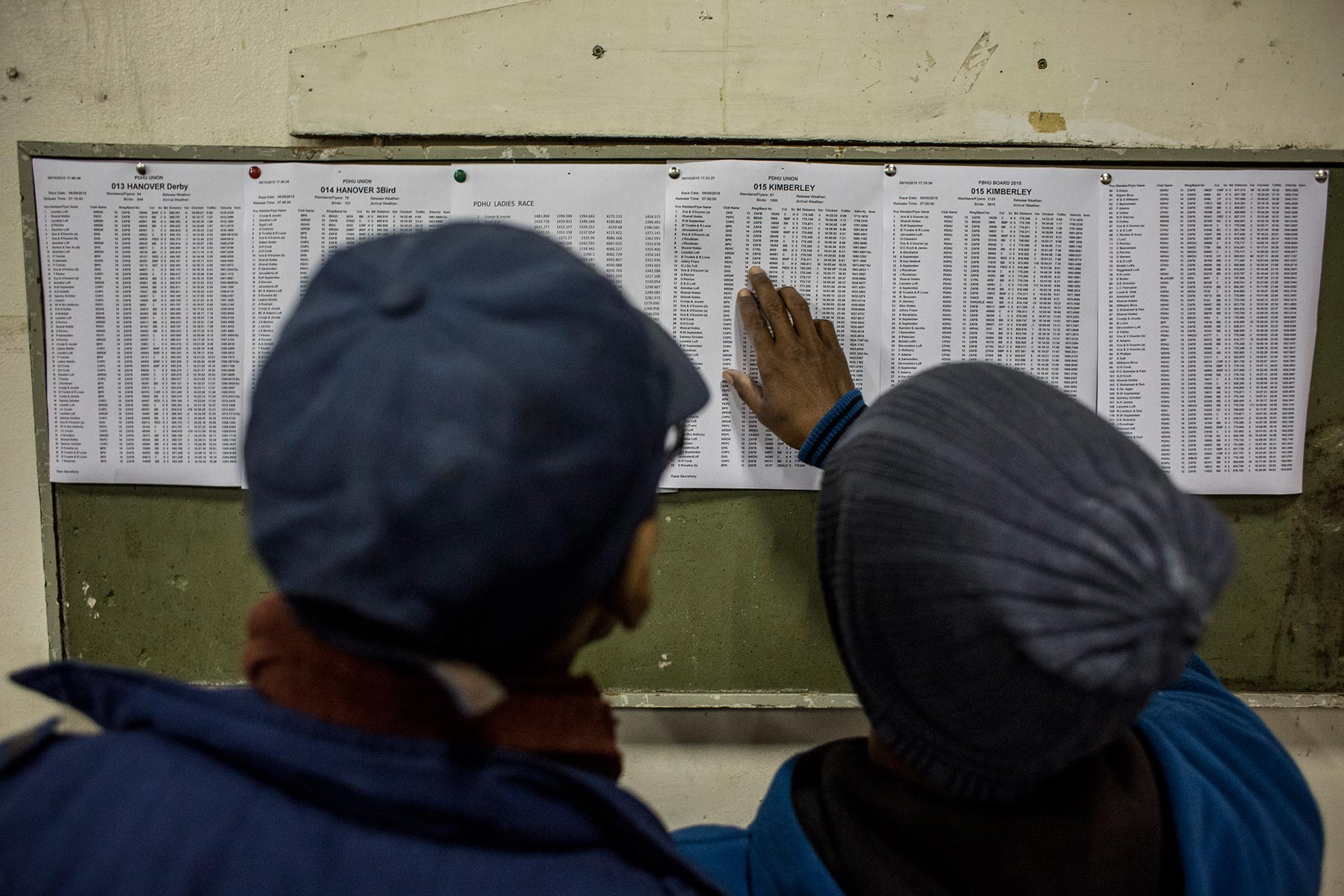

The race was won by Albert Lingenfelder from Villiersdorp, a farm town farther inland. “I’m shaking. I’ve been racing for 15 years. This is the biggest win of my life,” he said at the official prize-giving ceremony, held at a cricket stadium on the east side of Paarl on Sept. 13. Race organizers made long speeches about achieving unity through sport and about bringing people together after years of separation. Old Muslim men sat beside white Afrikaners in plastic chairs as the results were read out, standing as one to cheer Lingenfelder when his winning time was announced. Moerat was called up for a photograph with the new champion — the only man accorded the honor. He walked around for a few minutes, congratulating people, shaking their hands, and as the hall began emptying, he felt himself tire.

“If I win this, nothing will change,” he had said earlier of the race. “Either way, I’ll keep competing.”

He exited the hall and heard his son calling his name. The wind had dropped. The evening sun was warm against his skin. “OK,” he said, climbing into their car, and together, in silence, the two men drove the short distance home.