Selling American girls

Until recently, the victims were the ones being arrested

Series

This is part 1 of a seven-part series about sex trafficking.

On a cool, quiet Thursday night, crimes of all types unfurl on South Figueroa Street.

This is one of the main tracks for prostitution in Los Angeles, a strip where sex can be purchased from teenage girls on almost any given corner, where pimps, some of them gang affiliated, carefully guard their turf and property.

At about 200 blocks, most of them rough, the Fig, as it’s called, can hide a lot. In April it was hiding a 16-year-old named Stacey, missing since December.

She contacted a cousin on Facebook earlier that month, using someone else’s phone. She was with a pimp, she said. Then a big break: She called her mother from a blocked number, saying she didn’t know where she was and that she was scared.

After a frenzy of warrants for cellphone records from dozens of carriers, police narrowed the search to a Sprint number. But the ping from a cell tower isn’t pinpoint; the call was made within several hundred feet of a block on Fig, leaving Sgt. Brian Gallagher and his team to drive around and around, looking for Stacey on streetcorners, parking lots, motels and alleyways.

If he knew the identity of Stacey’s pimp, Gallagher, who runs the South Bureau Los Angeles Human Trafficking Task Force, would have an easier time of finding her. Pimps there operate much like narcotics gangs, each with his own turf or stretch of blocks where his girls work. If you know a pimp, you know where he places his girls. And if Gallagher found Stacey, he might be able to find her pimp, since the men tend to brand the girls with their monikers — their pimp names, often under a crown. Sometimes the tattoos are crude; other times, they’re in an almost girlish twirly script, like an ad for a cupcake shop or a princess costume.

But he doesn’t know who manipulated Stacey into jumping in and out of vehicles with men doing car tricks. He doesn’t know the name of the man she calls Daddy in her text messages to another girl, fretting that she needs to give him her money before she can eat or repay money she borrowed so she could eat.

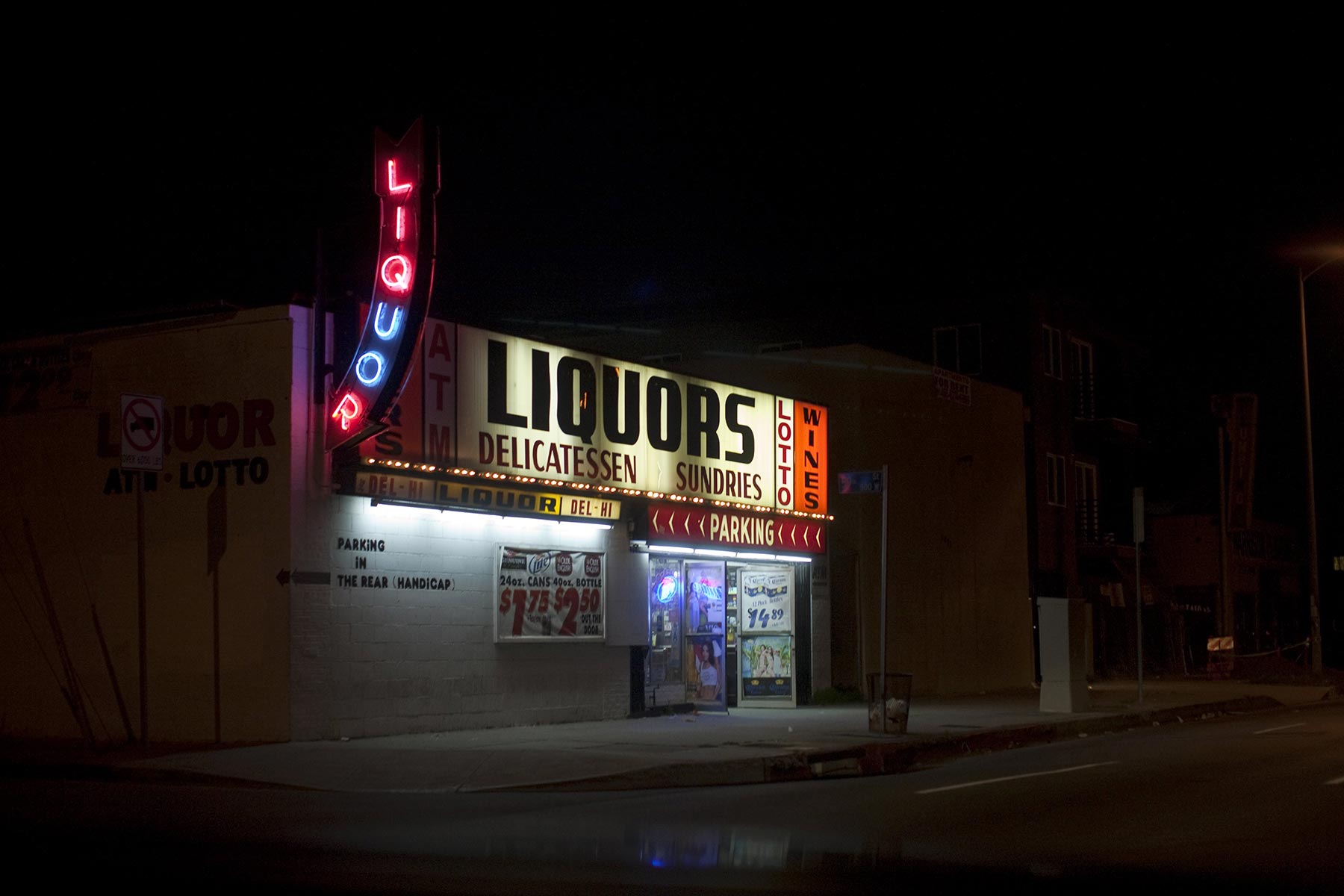

“This little girl is driving me crazy,” says Gallagher, squinting into the dark as he drives through South Los Angeles, an area he sums up in four words: “Churches and liquor stores.”

He and Officer Andrew Gonzalez drive up and down Fig for hours, day or night, whenever they can find the time, going back and forth on the radio, block to block, looking for Stacey, whose face sometimes seems to appear on other girls and then, mirage-like, disappear.

Stacey might not be the face of human trafficking for most, but she is a typical victim of domestic human trafficking in the United States: an American girl with more troubles than advantages, targeted by a predatory pimp and trafficked in her own town, in her own neighborhood, even.

According to the U.S. Justice Department, minors make up roughly half the victims of human trafficking in the U.S. and are the victims of the fastest-growing criminal enterprise after drug trafficking — worth an estimated $32 billion a year worldwide

Data from the National Human Trafficking Resouce Center indicate that of the 4,168 cases of trafficking in the U.S. reported on the center’s hotline in 2014, close to 3,100 of them involved sex trafficking. The data, released by Polaris, an anti-slavery nongovernmental organization, also show that roughly one third of those cases involved minors.

The fight against this kind of human trafficking is Sisyphean, with front-liners like Gallagher hoping for nothing more than maybe moving the racket to another area. “The most I can hope for is to displace it,” he says.

Night after night, day after day, he and his team go out, and “it never, ever slows down. It never stops,” says Gonzalez, who, like Gallagher, is the father of a teenage girl — a fact that never drifts far from their minds as they look at the faces of the girls they encounter.

When they describe the things they’ve seen — looking for missing girls as young as 11 or seeing what one violent pimp or another did to a girl — their cop masks, the face of calm while cuffing a john or questioning a stoned passenger of a hot-boxed car about missing girls, drop for a moment. Even after all their years of policing these streets, they still get incredibly invested in finding girls like Stacey, ready to take apart a neighborhood stone by stone to find to her.

Gallagher and his team seem to have developed a kind of super street vision. They can see a shadow move in the dark, sense a sideways glance from faces tilted away from them. Time and time again, driving around the poorly lit blocks, Gallagher would see a shadow in his peripheral vision and break off midsentence to radio Gonzalez before turning to chase down the shadow, but none of them turned out to be Stacey that night.

Gallagher’s familiar with the faces, the cars and the blocks, and he keeps hoping that others might come to know them and that developers will discover the area.

“These people don’t even have a Starbucks,” he says. This might not sit with those who fret about gentrification, but he would rather see people scowling over Frappuccino sales than dealing with the liquor store that charges girls $5 per trick to let them use its backroom.

“People gotta walk their kids to school past that … and all these motels that exist just for this,” says Gallagher, who says he has been writing Magic Johnson Enterprises, hoping it will go in, invest and draw some more-upscale businesses to Fig.

“Why can’t they come here and do what they did in the Bronx?” he asks, referring to Johnson’s efforts in the New York City borough, where he has attracted big box businesses such as Best Buy.

For now, there are no Starbucks on Fig. Although the girls who work the streets stop by McDonald’s and Jack in the Box now and again, they are monitored by pimps in vehicles in the parking lot, tracking the kids they sell to pretty much anyone who asks.

Motels are key players in the sex trafficking trade, sometimes complicit ones, sometimes reluctant.

In the 108 Motel parking lot, as Gallagher’s team handcuffs a john and the woman he tried to buy on a sunny Friday morning, the motel’s owner, Amit Shah, looks on, hands clasped behind his back.

“I don’t want this here … but they don’t listen,” he says of the pimps and johns. He points to a scar on his head and says that the last time he asked a pimp to take his business elsewhere, the pimp “glassed” him with a broken bottle.

As Officer Vanessa Rios sorts through the young woman’s purse, the woman, who goes by Cupcakes, explains why she’s there: Her baby is with her pimp.

“I just needed some cash. It’s hard being single,” she says. She’s not totally single, though. She has “MS” tattooed on her; Rios says this makes the woman’s pimp a guy who goes by MacSauce, a member of the Denver Lane Bloods. He owns her.

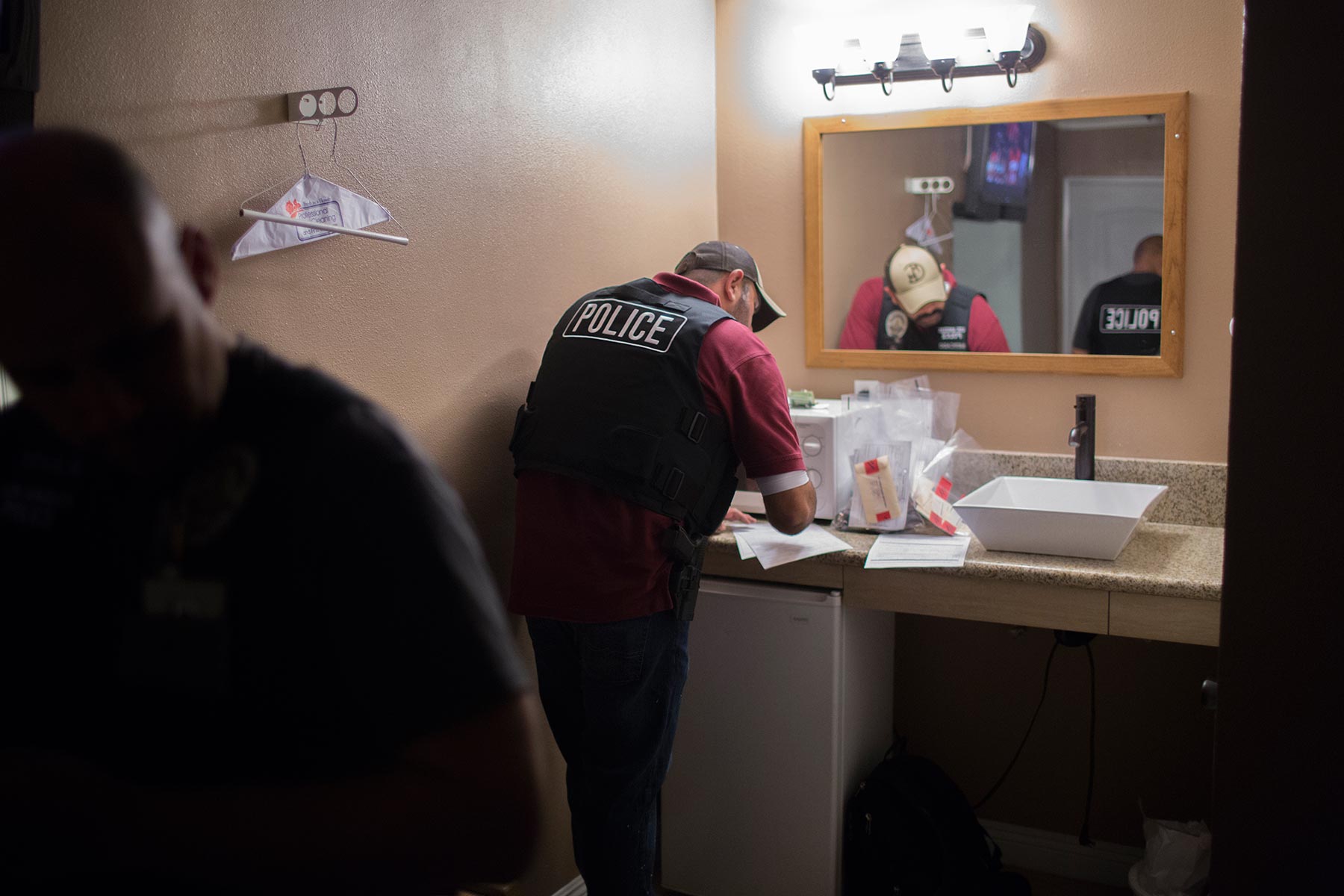

The motels are also staging sites for stings.

In a room in the 77th Street precinct, the plan for the night’s sting is laid out like a play on the field: undercover female officers there and there, with two sets of eyes watching them from there and there. Around the corner, in a motel with lumpy beds that smell like urinal cake, two rooms are rented out. Once the john agrees to a price and accompanies one of the female officers to a room — boom — he is cuffed.

He’s taken to a room where the officers ask for identification, fill out forms and place the men’s belongings in plastic bags. It’s a very smooth procedure, which the officers repeat, over and over.

Within a couple of hours, they’ve busted four guys, from a former bank robber to the private chef for a priest. The men sit in the motel room, handcuffed. There are mirrors on three walls and the ceiling. They have nowhere to look but down.