Voting-rights groups challenge electoral purges

Anger at Interstate Crosscheck, the controversial program that identifies potential ‘double voters’

By Greg Palast for Al Jazeera America

Photos by Zach D. Roberts for Al Jazeera America

Edited by Mark Rykoff, Jayati Vora

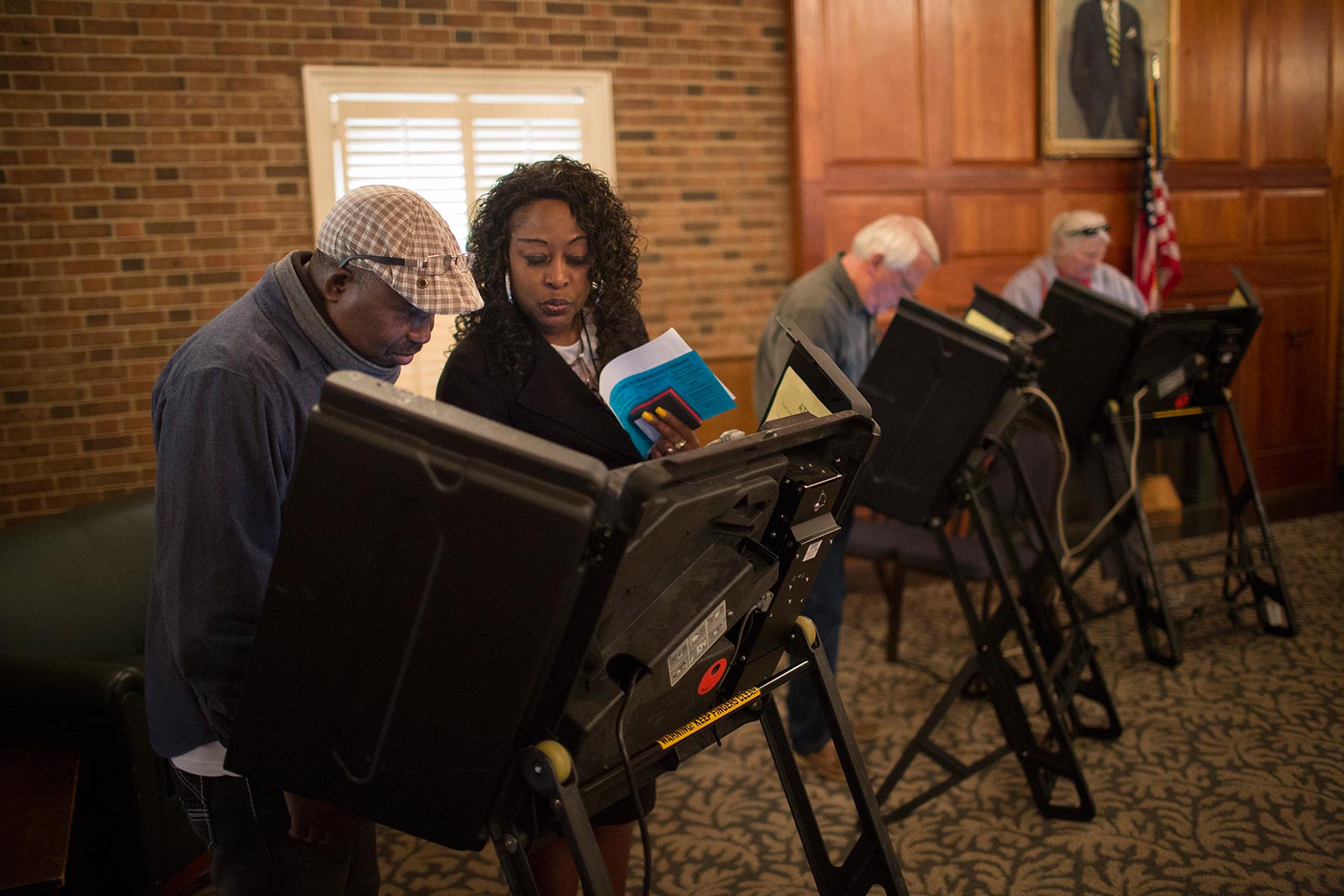

Above: Voters at the polls in Jamestown, North Carolina. (Photo by John Taggart / EPA)

Published on Tuesday, Nov. 4, 2014

GREENSBORO, N.C. — As control of the U.S. Senate hangs in the balance, voting-rights activists are preparing for a fight over the removal of suspected fraudulent voters and nowhere more so than the Southern battleground states of Georgia and North Carolina. They are responding to a six-month investigation published last week by Al Jazeera America, which revealed that millions of voters are at risk of being removed from the rolls in 27 states participating in the Interstate Crosscheck program, a voter-fraud detection system.

Using open-records requests, Al Jazeera America obtained the previously confidential Crosscheck lists of 2.1 million voters potentially accused of casting ballots in two different states in the same election, a crime punishable by 2 to 10 years in prison. The lists reveal that the supposed double voters were matched simply on first and last name, and middle initials, suffixes and Social Security numbers were ignored. Due to its shoddy methodology, the list captured far more black, Hispanic and Asian-American voters than their white counterparts, in large part because of the commonality of minority surnames.

Helen Ho, executive director for the legal advocacy group Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta, says, the investigation was a “bombshell.” While Ho’s immediate concern is protecting her community’s voters in today’s tight Senate contest between Democrat Michelle Nunn and Republican David Perdue in Georgia, she is leading national groups to take action against the misuse of the Crosscheck lists. She worries that Asian-Americans, many of whom share just a few common surnames — such as Chung, Lee, Patel and Kim — are particularly vulnerable to Crosscheck’s system of using little more than first and last name to identify potential double voters. “No one knew what was going on,” says Ho of Georgia’s participation in Crosscheck.

AAAJA issued a statement urging voters experiencing difficulty casting their ballot today to call their multilingual hotline for help.

For more on “double voters,” read Al Jazeera America’s investigation into the Interstate Crosscheck program and post-election analysis.

Watch America Tonight's coverage of this story:

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

In Greensboro, the Rev. William Barber II gathered the faithful at sunset for one of his Moral Monday rallies. It would be the last before Election Day, in the nation’s closest, most bitter and most expensive Senate race: the showdown between the incumbent, Kay Hagan, Democrat, and the state legislature’s Republican leader, Speaker Thom Tillis.

Before mounting the stage, Barber spoke with Al Jazeera America about the Interstate Crosscheck revelations. “Their computer system has already been proven to have quite a few glitches… it’s so bad at this point of the elections to create that kind of hysteria,” he said. “The claim of fraud is fraudulent. What they’re afraid of is people voting one time, not people voting two times. And the more people vote one time, it means that not many people will be voting for them, for the extremists in our state.”

The North Carolina chapter of the NAACP, of which Barber is president, has warned the state government about Crosscheck-style electoral purges. “We’ve just sent a serious legal letter to the State Board of Elections calling this into question,” he says. “Because whether it’s driving [while] black or attempting to profile voters by black or by brown, it is wrong in America and we cannot tolerate it.”

In Raleigh, the state capital, Bob Hall, executive director of the nonpartisan voter-rights group Democracy North Carolina and a man whose legendary career in voting rights has won him a MacArthur “genius award,” sees Crosscheck as “a way to intimidate and scare people about there being a lot of fraud by bringing together millions of names and saying, ‘Oh my God! Some of them match!’” The Al Jazeera America exposé, Hall says, confirms what he suspected: “These are false matches.”

Hall assumes his own name is on the list of potential criminal double voters. “I know there is more than one Bob Hall with my birth date who lives among the 28 states” that were participating in Crosscheck. (The 28th state, Washington, dropped out earlier this year after receiving Crosscheck’s list of 217,247 pairs of suspected double voting Washingtonians.) In Georgia and Virginia alone, “Robert Hall” is listed as having voted 69 times. Of those matches, 41 have mismatched middle names. (Check your own name using our searchable online database).

Crosscheck is just one more element of North Carolina’s new, restrictive voting laws, Hall says, which limit early voting and will require voters to produce additional identification. He calls it “a replay of the Jim Crow monster” from the era of mandated racial segregation, “and here it is back again, terrorizing people.” Hall and his group are among the organizations that plan to fight these Crosscheck-inspired voter purges.

In Atlanta, too, lawyers for the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan voter-registration group, have already begun analyzing the Crosscheck lists made public by the Al Jazeera America investigation. The group’s founder, Rep. Stacey Abrams, who is also the Democratic Party’s leader in the state legislature, has come out strongly against the operation of “the nefarious ‘Interstate Crosscheck’ system, [which] seeks to purge hundreds of thousands of voters in Georgia based on common last names and scant else,” she says. Given the likelihood of common names for African-Americans, Latinos and Asian-Americans, this system is fraught with dangers for eligible voters, Abrams adds.

She is particularly angry that participation in the program was carried out in secret, unlike in North Carolina, where officials publicly proclaimed their hunt for alleged double voters. “If the [secretary of state] believes this is the right thing, then he should present his reasons to the legislature and the voters rather than operating in secret.”

In Kansas, attorney Robert Eye has already crossed swords over voting rights with Secretary of State Kris Kobach, the key promoter of Crosscheck. Eye particularly objects to Kobach’s promise to the other participating states that Kansas will bear all the computing costs of creating the potential purge lists. “Your cost: $0,” according to one of Kobach’s Powerpoint presentations to a convention of state elections directors.

Eye disputes the Crosscheck premise that there are thousands, even millions, of criminal double voters. Since Kobach began promoting Crosscheck, not one Kansan has been convicted of voting twice. “This purported fix to a nonexistent problem truly undermines the franchise,” says Eye. “And it adds insult to injury that an official is using his official position to promote a personal agenda.”

Kobach, who is locked in a tight re-election race, did not respond to requests for comment.

Back in Greensboro, Barber recites local history. It was in this small Southern town that the beating of students conducting a sit-in at the local Woolworth’s in 1960 occurred, a milestone in the civil rights movement. The state has made it an official tourist destination.

Barber’s rally marks the 35th anniversary of the Greensboro massacre, the killing of five protesters by the remnants of the Ku Klux Klan, an event without a tourist marker. “We’ve been through too much to go backwards,” he says to the gospel sounds of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

Greensboro is the residence of an astonishing 3,735 voters who supposedly cast ballots illegally in the presidential election, in both North Carolina and Virginia. Or, at least, that is how they are listed in the Interstate Crosscheck files.