The tribe that said no

HowoneroguetribalmembertriedtodragtheOglalaSiouxintopaydaylending

By Nicholas Nehamas for Al Jazeera America

Photos by Patrick Cavan Brown for Al Jazeera America

Produced by Alex Newman, Joanna S. Kao, Lam Thuy Vo

Edited by Katherine Lanpher, Mark Rykoff

The stories and graphics for Payday Nation were reported and produced in collaboration with the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University in New York. Joanna Zuckerman Bernstein and Julia Harte contributed reporting and research to this story.

Published on Wednesday, June 18, 2014

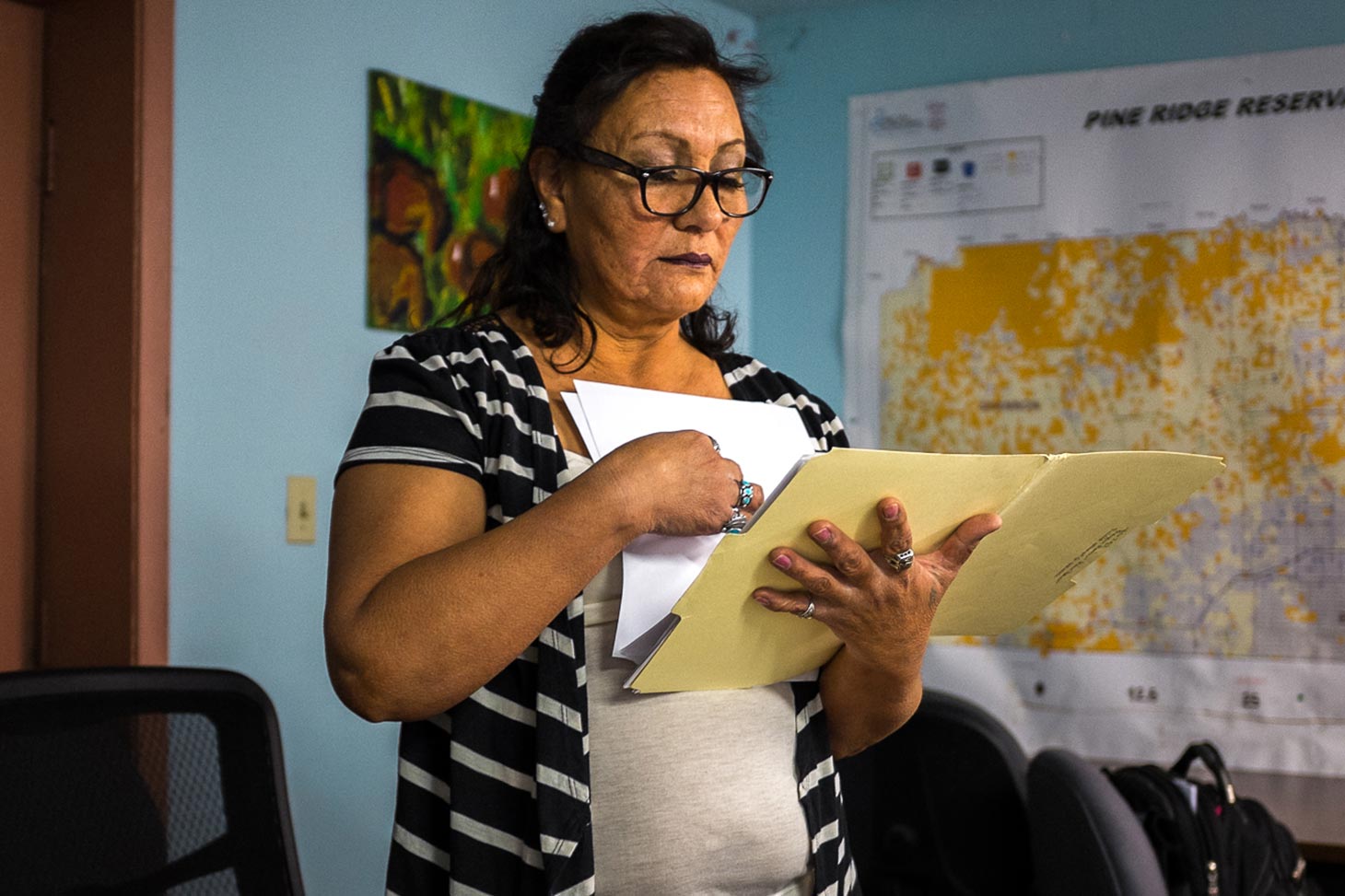

PINE RIDGE, S.D. — Arlene Catches the Enemy was skeptical when a member of her Native American tribe, the Oglala Sioux of South Dakota, came here to preach about how online payday lending would change lives on the tribe’s Pine Ridge reservation.

Raycen Raines, a former insurance salesman, was the idea’s charismatic evangelist. The business of lending money to poor people at triple-digit interest rates was booming, said Raines. He told tribal officials in late 2011 that they, too, could get a cut of the action and bring in “a free income stream” to the tribe.

The Oglala Sioux could certainly use the money. Their reservation, which stretches across approximately 2 million acres of rocky hills and rolling plains, is one of the poorest areas in the United States. Tribal officials estimate the unemployment rate here at 80 percent — even worse in the winter when seasonal work on farms and ranches dries up.

But the tribe ultimately turned Raines down. “It was predatory lending,” said Catches the Enemy, who works in the tribe’s economic development office.

Slideshow: The World of Arlene Catches the Enemy

Payday loans are short-term loans with interest rates usually between 400 and 700 percent or higher. All a customer needs to obtain a loan is access to a computer and a personal bank account. The borrowers, who often have cash-flow problems and aren’t able to get loans from traditional banks, usually agree to let the lender deduct interest and other payments from their bank accounts automatically.

Besides her problems with the loans, Catches the Enemy said tribal officials felt Raines’ proposal shortchanged the tribe. Most of the money would go to a non-native-owned company, Arizona-based Cash Cloud LLC, which actually ran the lending business.

Despite the tribe’s refusal, Raines went ahead and set up an online payday business anyway. FastMoneyStore.net used a post office box on the reservation as its legal address, even though Cash Cloud made and serviced the loans from Arizona. Soon Raines acquired partners. Today, at least 14 payday lending websites claim to do business from Pine Ridge. Besides Cash Cloud, the other companies that make the loans appear to be based in Utah, Texas, Canada and Belize, according to an analysis of corporate records and government documents.

Catches the Enemy had no idea Raines had set up the lending companies without the tribe’s approval. She said the first she heard of it was when Al Jazeera asked about the lender’s connection to the Oglala Sioux. “We’re doing what?” she exclaimed in surprise over the phone.

In an interview at her Pine Ridge office, where an animal pelt and several feathered arrows lie across a box of files, Catches the Enemy said a tribal court had issued a temporary restraining order in early 2012 against Raines, preventing him from doing business on the reservation, and that the order had been served upon him with his attorney present. She said she would contact a lawyer to reopen the case. (Raines did not respond to multiple requests for comment, including phone calls, emails and a written message left at his house on the reservation.)

“We need to investigate. We have to look into it,” the tribal president, Bryan Brewer, said as he walked to a groundbreaking ceremony for a wind turbine the Oglala Sioux plan to erect behind a small tribal casino. “I’m really sorry we don’t know what’s going on.”

Trouble off the reservation

The tribe’s misadventures with payday lending have their roots in Utah, where two businessmen – Chad Jardine, a former marketing executive, and Blake Collins, an Internet entrepreneur – set up an online lending company called Flobridge in 2009. State regulators soon began to notice their success. In December 2010, the state of Idaho issued a cease-and-desist order to one of their lending websites. The order stated that the company had issued payday loans without a state license and illegally attempted to garnish the wages of two customers who didn’t pay back their loans on time. (Jardine and Collins did not respond to requests for comment.)

By then, Jardine and Collins had incorporated a new company, Cash Cloud, in Arizona. It was only a matter of time before new cease-and-desist orders began arriving from other states that regulate payday lending. But Jardine and Collins could continue doing business if they found a sovereign native tribe to serve as their legal shield: The principle of tribal sovereignty offers immunity from the enforcement of state laws. Lending businesses affiliated with tribes are able to operate even in states that cap interest rates on payday loans.

If a payday company has a legal affiliation with a tribe, “there’s really nothing we can do” to stop them in court, explained Deborah Bortner, director of the consumer division of Washington state’s Department of Financial Institutions.

That’s where Raines came in.

Raines describes himself as a “Renaissance Indian.” He stands just under 6 feet tall, his long black hair flowing in curls down his neck. Although he was born in Portland, Oregon, and raised in Alaska, Raines has Oglala blood on his father’s side and always felt a connection to Pine Ridge.

In 2011 he moved to the reservation, styling himself an “economic development consultant in Indian Country,” according to promotional materials he submitted to the tribe. In an email to a tribal official, Raines talked up his dedication to the Oglala Sioux. “I don’t have a wife and kids,” he wrote, “as my career with bringing economic development to the [tribe] is my wife and kids.”

On a cold night in January 2012, Raines made his pitch to the Wakpamni district, one of nine regional subdivisions that make up the reservation. Although the tribe elects a president and a legislative council to govern the reservation, districts like Wakpamni have the power to make business deals without permission from the council. Raines and his relatives lived in the district, and he had allies there.

If Wakpamni approved Raines’ plan, Cash Cloud could start making loans around the country as an “official tribal entity,” free from interference by state regulators.

Around 40 people showed up that night to the district headquarters, a circular blue building a few miles east of Pine Ridge, the reservation’s largest town (population 3,308).

The meeting grew heated, according to Catches the Enemy, who was in the audience.

Raines was working the crowd.“Does everybody here have a good job?” he asked, according to minutes of the meeting. “I didn’t think so.”

“These big industries need to move onto sovereign land,” Raines continued.

Raines had brought with him a draft contract that created a partnership between Cash Cloud and the Wakpamni district. Cash Cloud would pay a fee of $5 per new loan, up to $100,000 per month, into a bank account held by Raines. After the $100,000 threshold was reached, the lenders would pay $2.50 per loan.

Raines and the district would then split the monthly payments 50-50, which Raines said was fair since he had done “the work and put in the money and expertise to make this opportunity happen.”

Sandy Two Lance, the president of the Wakpamni district, backed the proposal. “I support what they’re doing because we have nothing,” Two Lance said at the meeting. But the other three members of the Wakpamni executive board expressed skepticism.

“Everything is in [the lenders’] favor,” said Richard Little Hawk, a member of the board. “I want to see a meeting of open negotiation to reach an agreement that is beneficial to everyone.”

“He wants more money,” Raines responded. “I don’t have any more money to give you.”

But Little Hawk and the other board members wouldn’t budge. A few days earlier, the tribe’s attorney had written Little Hawk an alarming email. “Entering into this agreement,” the attorney warned, “would result into a huge legal liability” for the tribe and the district if state regulators decided to sue.

Two Lance realized she didn’t have the votes she needed on the executive board. So she put the matter to a floor vote, a move that violated district rules because the meeting lacked a proper quorum.

“If we make $2.50, that is $2.50 we didn’t have before,” said a member of the audience who seconded Two Lance’s motion despite its procedural improprieties.

Only one person in the meeting hall voted against the contract. Little Hawk and the two other board members abstained in protest.

For Two Lance, the matter was settled. “The consensus is here,” she said.

“It’s not going to be legal, but I’m going to do it and see what happens,” she added, before signing the contract.

Predatory lending?

To get the business going, Raines set up the Wakpamni Lake Community Corp., a holding company that legally owns the lending websites. But the Wakpamni district board refused to honor the contract Two Lance had signed, saying she had done so illegally. Raines kept making the loans anyway.

The lending company therefore operates without the tribe’s official sanction. It does not share any profits with the tribal government. “The tribe has no ownership in that business,” confirmed Bob Palmier, director of the tribe’s revenue office.

That means the company does not have a legal affiliation with the Oglala Sioux, according to tribal officials and legal experts. It also suggests that state regulators could sue if they judge Raines’ company to be breaking state laws.

The Wakpamni Lake company gets around $4,000 a month from the lenders, according to Geneve Lone Hill, the company’s president and a friend of Raines. Lone Hill said half of that money goes to Raines, who uses it to help fund a native culture performance troupe and another group devoted to saving wild mustangs. Lone Hill gets the rest. She said she uses her share to buy fresh meat, fuel and other supplies for needy families in the area.

Lone Hill said Ogala Sioux officials have systematically ignored the Wakpamni community, an isolated area with approximately 800 residents on the reservation’s eastern border. “We don’t get services out here,” Lone Hill said. The payday money isn’t much, she added, “but it’s better than nothing.”

She also said the payday lending business could be construed as “predatory.” In 2013, consumers filed 59 complaints against six of the Wakpamni online lending sites, according to data from the Federal Trade Commission. Most of the complaints, which came from residents of 20 different states, accused the companies of charging unadvertised, hidden fees and harassing customers with threatening phone calls and emails.

Lone Hill said she had no problem with the loans because they were not made on the reservation.

Besides, she added, the Oglala Sioux have suffered long enough. “We’re getting hurt here too by our own people and our government and our country, who are not treating us fairly,” she said.

“When you deal with people who are impoverished, they will go for any idea that promises cash,” said David Mills, the director of the tribe’s economic development office and Catches the Enemy’s boss.

Catches the Enemy said her opposition to payday lending didn’t make her “a popular person” on the reservation. But she knew she was right to oppose the project: Her daughter, Yolanda, had lost the title to her truck several years earlier after taking out a car title loan, which like a payday loan comes at a high interest rate.

Elizabeth Rowland, who serves as treasurer of the Wakpamni district, agreed with Catches the Enemy. Her son, she said, had almost lost his van after taking out a similar loan.

After that experience, Rowland said she gave him some simple advice: “Don’t ever get involved with one of those loans again.”