Titanic canal project divides Nicaragua

Critics say world’s largest-ever engineering endeavor marks new era of colonization

A deep divide

Part one of a five-part series examining the impact of the Nicaragua canal.

If a shadowy Chinese billionaire has his way, the fishermen’s shacks that dot the shores of Brito, on Nicaragua’s Pacific coast, will soon be barreled over. Waves of multiton trenchers and dredging machines will enter the mouth of the Brito River and churn their way inland before entering Lake Nicaragua, Central America’s largest and most biodiverse reservoir. Then they will slice their way through the rain forests, wetlands and indigenous communities that typify the country’s east, until they reach Rio Punta Gorda, on the Caribbean coast.

Finally, they will have given birth to the 172-mile Nicaragua Interoceanic Grand Canal — what has been billed as the largest engineering endeavor in history.

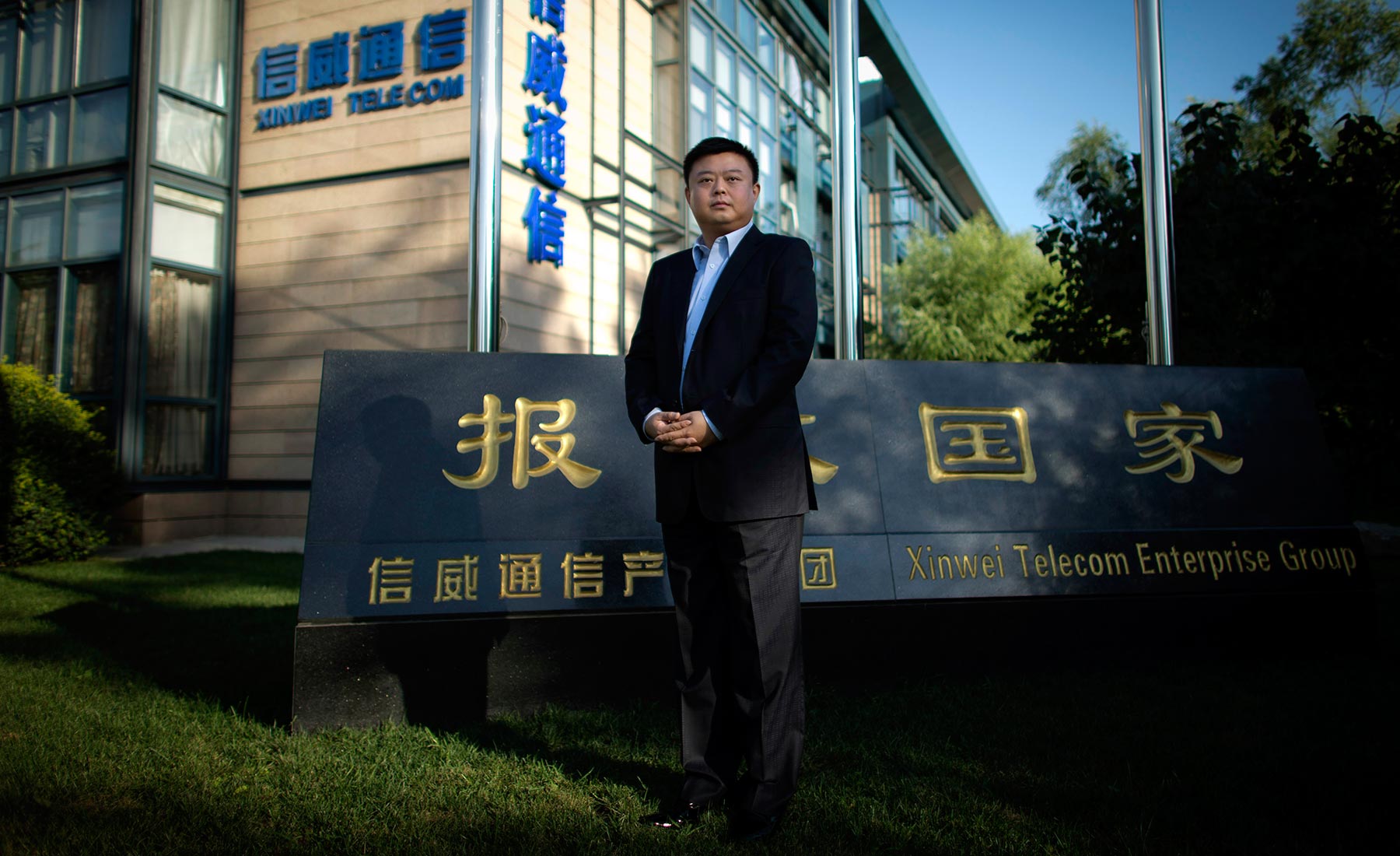

But the project, which critics claim marks a new era of colonialism in Nicaragua, has so far raised eyebrows as much for its secrecy as for its titanic ambitions. More than two years after its announcement, a final exact route for the canal has yet to be pinned down. Very little is known about Wang Jing, the Chinese telecom magnate who has been granted a 50-year concession to build and operate the canal, with the option to extend the concession for 50 years. One has to strain to see signs of construction along the tentative route. And Nicaraguans are still waiting for a long-promised environmental impact study.

In December in Brito, at a ceremony that has come to epitomize the project’s nebulous history, Wang inaugurated the canal’s construction. But independent journalists and international media were kept away from the event. Wang insisted that all the canal’s problems have been solved but provided no details. Among scores of questions, critics wonder how the Hong Kong Nicaragua Development (HKND) Group, the holding company created by Wang to finance the project, will raise the estimated $50 billion needed to complete the project in five years — a time frame that has been roundly panned as quixotic.

Below: A panoramic view of the Nicaraguan coastline near Brito.

Drag left and right to see the entire photograph.

“We know it’s an ambitious plan,” said Telémaco Talavera, a spokesman for the government-run Nicaraguan canal authority. Although Al Jazeera saw no signs of construction during a recent visit to Nicaragua, he insisted that construction has already begun on the highways that will hug the route — byways that will facilitate transport of the heavy machinery required to carve the canal. The environmental impact study will be submitted by May by London-based Environmental Resources Management, he said. And the canal’s exact route, he insisted, will soon materialize. As will the jobs, President Daniel Ortega’s prized promise, which he has said will transform Nicaragua from the hemisphere’s second-poorest nation, where 40 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, into a regional economic powerhouse, with annual economic growth of 14.6 percent by 2016.

“During the canal’s construction, we estimate that 50,000 jobs will be needed,” Talavera told Al Jazeera. “Among those, 25,000 will go to Nicaraguans, 12,500 to different nationalities and 12,500 to Chinese workers.” Once completed, operation of the canal will require an estimated 200,000 workers. The Nicaraguan government, said Talavera, is focused on assuring that most of those jobs go to Nicaraguans. “During the canal’s construction, we will be capacitating Nicaraguans as much as possible for the operational phase,” he said.

Besides the canal, the 50-year concession allows HKND to build seven subprojects, including airports, golf courses, deep-water ports and free trade zones. HKND is exempt from all liability related to the projects — an audacious gift, opponents claim, that hands over national sovereignty to a mysterious holding company. Talavera refutes those claims. He says each subproject will have to provide an environmental impact study and seek approval by the National Commission for Canal Development.

Talavera said strict environmental standards will apply to Lake Cocibolca, also known as Lake Nicaragua. HKND will be responsible for any environmental disaster to beset the lake. “The responsibility — and that is established — falls on licensee [HKND],” he said. Care of the lake, home to 40 fish species, some of them endangered, will be governed by strict international protocols (HKND did not respond to several Al Jazeera requests for comment). Talavera insisted that there is little to worry about. The Panama Canal, he noted, has seen over 1 million ships pass through its locks in 100 years without any environmental disasters.

But Nicaraguan environmentalists are horrified. They say the concession is a new form of colonization. “Nicaraguan citizens will have to face grave challenges in order to rid themselves of colonizers,” Mónica López Baltodano, an environmental lawyer and the head of Fundación Popol Na, a Nicaraguan nongovernmental organization, told local media in December. “We’re going to have to initiate a struggle for national liberation, much like Sandino,” she said, referring to Augusto César Sandino, a guerrilla leader who led a struggle against U.S. occupation of Nicaragua in the 1930s.

The no-bid concession, fast-tracked through the National Assembly in a day, with no public debate, violates Nicaragua’s Constitution and more than 10 international environmental treaties, she said. “The constitution established that any concession of natural resources has to be approved by all the municipalities affected and all representatives on indigenous lands,” she said. “This concession does not do that.”

López Baltodano and other canal opponents recently filed a constitutional complaint with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, based in Washington, D.C. During an appearance before the commission in March, she warned that roughly 120,000 people will be directly uprooted by the project. “But the project’s biggest threat,” she said, “falls on Lake Cocibolca.” More than 200,000 people rely on the lake for their drinking water. But to allow the passage of the massive container ships, dubbed Triple E, that are too large to fit through the Panama Canal, nearly the entire path through the lake, 65 miles, will have to be dredged. That’s because the lake averages a depth of 13 yards and Triple E ships, capable of carrying 18,000 containers and measuring one-quarter of a mile long, need a depth of 32 yards to move freely. For them to cross the lake, an estimated 700 metric tons of rock and soil will have to be dredged from the reservoir’s bed — enough to cover 120 square miles, roughly the size of Atlanta, in three yards of sediment.

There have been some 70 other attempts to build a canal across Nicaragua — all unsuccessful. The U.S. shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt set his ambition on Nicaragua in the mid–19th century. Obsessed with ferrying passengers from the eastern United States through Central America to California during the gold rush, Vanderbilt started a canal route. But he abandoned his efforts in the 1860s amid territorial spats between the U.S. and England. By the end of the century, the U.S. began to increasingly eye Panama for a canal path.

During the 1920s and ’30s, Sandino, the diminutive son of a wealthy landowner, waged a guerrilla war against the Unites States, which intervened in Nicaraguan affairs six times before occupying the country continuously from 1912 to 1925. Perhaps inspired by Simón Bolívar, the Venezuelan liberator who fought for an integrated Pan-America, Sandino called for political unification of Latin America to resist the Colossus of the North. One of his principal demands was to guarantee that a Nicaraguan canal would remain under Latin American control. U.S. troops never seized Sandino. Throughout the region, he became an emblem of resistance to U.S. imperialism. Declared a national hero by the National Assembly in 2010, he continues to shape national identity.

In the early 1990s, Ortega, whose ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front party honors Sandino's legacy, dismissed talk of a Nicaraguan canal as an affront to national sovereignty. “I would never risk the great lake [Cocibolca] for all the gold in the world,” he said. But critics say that Ortega now mocks the party’s revolutionary ideals. While he still fumes over U.S. imperialism, critics accuse Ortega of dismantling the revolution. Lately he has framed the canal as vital to national sovereignty. The project, he said recently, will inject Nicaragua with much-needed cash flow and eradicate extreme poverty. He recently brushed off concerns of Chinese clout in Nicaragua. “The Chinese have not arrived in Nicaragua with occupying troops,” he said in December.

If the Panama Canal symbolized U.S. hegemony in the Western Hemisphere at the turn of the 20th century, the Nicaraguan canal may come to crystallize Chinese dominance in the region in the new millennium. Beijing has not publicly supported the canal project, despite Wang's ties with top Chinese government officials and although several Chinese companies are involved in the canal’s construction and planning. That Wang's telecommunications company, Xinwei, has received funding for overseas projects by the China Development Bank does not prove that Beijing is pulling the strings in Nicaragua.

But China and Latin America watchers say it’s hard to picture such a herculean investment — some experts believe the canal will require upward of $100 billion — without direct Chinese government involvement. “This project, if it goes forward, will only go forward with the overt or covert support and financial backing of the Chinese state,” said Evan Ellis, a professor of Latin American studies at the U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute. “That’s simply because the amount of money, coupled with the relatively low amount of transparency in the Nicaraguan political system and contracting system, makes it very difficult for them to raise the $50 billion or so that they need, at market rates, through open financial markets.”

The Nicaraguan canal would be just one — though certainly the largest — of dozens of joint Chinese infrastructure projects in Latin America in recent years, including a railway system from Peru to Brazil and hydropower projects in Ecuador and Argentina. Analysts view the project as a component of surging investment in the region, which has seen trade with China grow from $12 billion in 2000 to $262 billion in 2013. Last year Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged to boost trade with the region by $500 billion in the next decade. Analysts point out that Nicaragua, with its low labor costs and its proximity to Mexico and the United States, is ideally situated to serve as a manufacturing and distribution hub — something the canal would only enhance. “Do I think that China would have a strategic interest in a passageway of this sort? Yes, I do,” said Margaret Myers, the director of the China and Latin America program at Inter-American Dialogue in Washington, D.C., before adding a note of prudence. “But that doesn’t mean that it’s backing it.”

For Nicaraguan indigenous groups and landowners in the canal’s path, there is little doubt. “Fuera chinos” [Get out, Chinese] has become a rallying cry at protest marches. In the most violent demonstrations to date, over 50 Nicaraguans were injured and dozens arrested after protesters blocked main arteries into Managua, the capital, in December. Although most detainees were quickly released, six peasant and indigenous leaders were held for several days. Local human rights groups called their detention a kidnapping and blamed Ortega for the violent repression.

Roger Guido, the owner of a small-scale banana plantation, has helped organize opposition to the canal in the western town of Rivas. He blames the Chinese government, which, he says, wants to take away all his land. “What they really want is to steal the land so they can convert this country into the backyard of the Chinese,” he said. But he saves some of his scorn for his president. “Ortega will be remembered as the one who did the most harm to his country. He’ll be remembered as the most greedy caudillo in history.”

As the canal route works its way east from Lake Cocibolca, it will bisect wetlands, rain forests and indigenous territory, including that of the Rama-Kriol communities, whose land stands to be expropriated, in what human rights groups call a violation of the constitution. Neglected by the government for generations, the Rama have fished and tended subsistence crops like corn and yucca. Their disdain for Managua ran so high during the Contra war of the 1980s that some members, along with Miskitos, sided with U.S.-backed counterrevolutionary forces in their fight against the Sandinistas. But today the Rama view the canal as a bigger threat.

Becky McCray, an attorney for the Rama, fears that the Rama language, spoken by only a handful of people, will be wiped out if the group is displaced by the canal’s construction. A complaint filed last year to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights argues that the Rama community was never consulted before the project was fast-tracked through the National Assembly. “If the project is implemented, the strong possibility exists that the Rama language in the community of Bangkukuk Taik will be extinguished as its last speakers are forcibly displaced,” McCray told the commission on March 16. “The community continues to demand its rights, claiming the title to its collective land, which the Nicaragua government intends to usurp for the canal’s route.”

At his banana plantation in Rivas, Guido insists that peaceful resistance is the best means to oppose the canal. He vows to extend the protests, until now confined to villages directly in the canal’s path, to cities across the country. “During the revolution, I worked with the Sandinistas, and we have never seen anything like what is happening today,” he said. “We’re not in agreement with this, and we’re going to fight until the end.”

Additional reporting by Kate Kilpatrick

Correction: Al Jazeera erroneously cited Telémaco Talavera as saying the canal's environmental impact study would be ready by May. Mr. Talavera told Al Jazeera it would be ready by the end of April. The London-based Environmental Resources Management said the impact study will be ready in May.