The billionaire behind the canal

Wang Jing’s megaproject furthers China’s aims in Latin America and deflates economic importance of Hong Kong

A deep divide

Part five of a five-part series examining the impact of the Nicaragua canal.

The telecom tycoon who plans to build a $50 billion interoceanic canal across Nicaragua, Wang Jing, 42, has been described in Chinese media as a “round-faced, thick-eyebrowed, big and tall man who knows how to keep a low profile internationally.” A Chinese business analyst said that Wang is “incredibly arrogant” and that his project is “absurd” in its lack of environmental feasibility. Wang, however, has repeatedly emphasized how ordinary he is, describing himself as “an exceedingly simple man.”

But to the many critics of the canal project, both inside Nicaragua and out, such statements have only increased speculation that Wang is the frontman for a state-supported extension of soft Chinese power into an area more often seen as the diplomatic backyard of the United States.

Some government links seem obvious. Wang’s Beijing-based Xinwei Telecom Technology Co. was partly funded by China’s Ministry of Post and Telecommunications and partially owned by state-owned enterprise the Datang Telecom Technology and Industry Group. The Xinwei website boasts photos of Wang and other company executives flanked by the likes of President Xi Jinping, Premier Li Keqiang and National People’s Congress Standing Committee Chairman Zhang Dejiang.

Public records show that Xinwei in February signed a memorandum of understanding to collaborate on public works projects with Beijing officials — the latest of several indications of Xinwei’s long-running ties to local and national government. Despite Wang’s claims that he is not a member of China’s ruling Communist Party, a man who fits his description has participated in military celebrations and other party-related activities, records show. Beijing party officials did not respond to requests to confirm the nature of his role in local government.

Xinwei is reported to have several contracts to supply the Chinese military with technology. The company’s slogan is “Xinwei’s spirit — independent innovation, devotion to the country.” And if that devotion weren’t already clear, Wang plays People’s Liberation Army songs in the corridors of the company’s Beijing headquarters twice daily, Taiwan’s Want China Times news site reports, suggesting that Wang is concealing a military background from the public.

Meanwhile, government media coverage of Wang’s audacious Nicaragua project has waxed poetic.

A video published online by China’s state-run Xinhua news agency in December lauded the project’s “special value,” offering Chinese and international shippers shorter trade routes.

“China’s bilateral trade with Latin American will increase tremendously,” Zhang Shixue, a researcher on Latin America at the Chinese State Council–affiliated Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told Xinhua. “This canal is very much in Latin America’s best interest and in China’s best interest. It’s a kind of win-win.”

But other facts cast doubt as to whether the project is a state venture. The proposed canal doesn’t bear the hallmarks of a government-backed bid for infrastructure cum international soft power abroad. It lacks the wealth of investment, speed and efficiency of Beijing’s traditional undertakings. And it’s such an environmentally unfeasible, potentially embarrassing undertaking, some critical analysts say, that many believe it couldn’t possibly be backed by China’s increasingly savvy foreign policy decision-makers.

HKND, the Hong Kong–based holding company that was awarded a 50-year concession by the Nicaraguan government to build and operate the canal, initially agreed to grant Al Jazeera an interview with Wang. But the company ignored subsequent phone calls and emails after interview questions regarding popular opposition to the project and possible government ties were submitted. Xinwei headquarters in Beijing did not respond to phone interview requests, and staffers at the company’s Chongqing offices declined to comment.

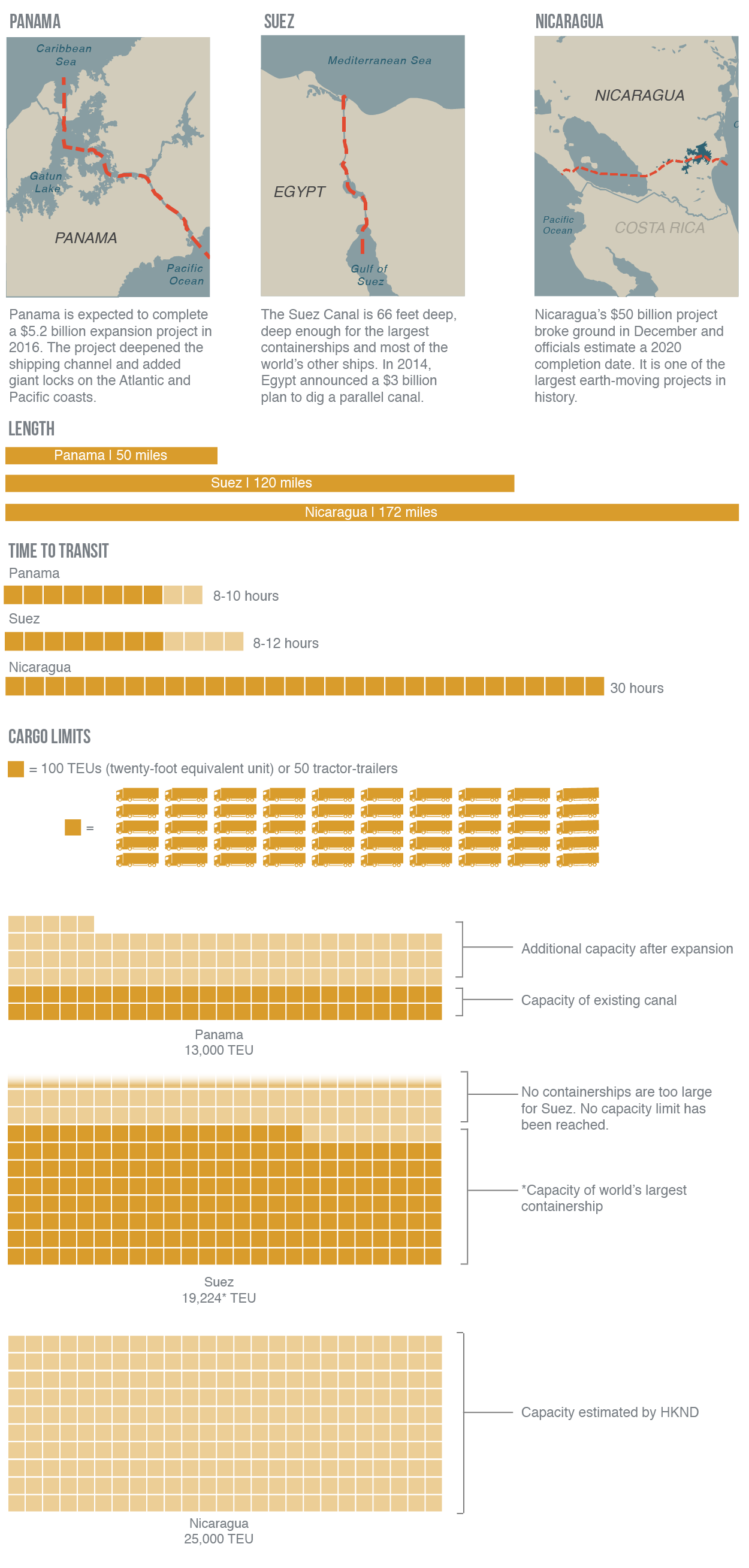

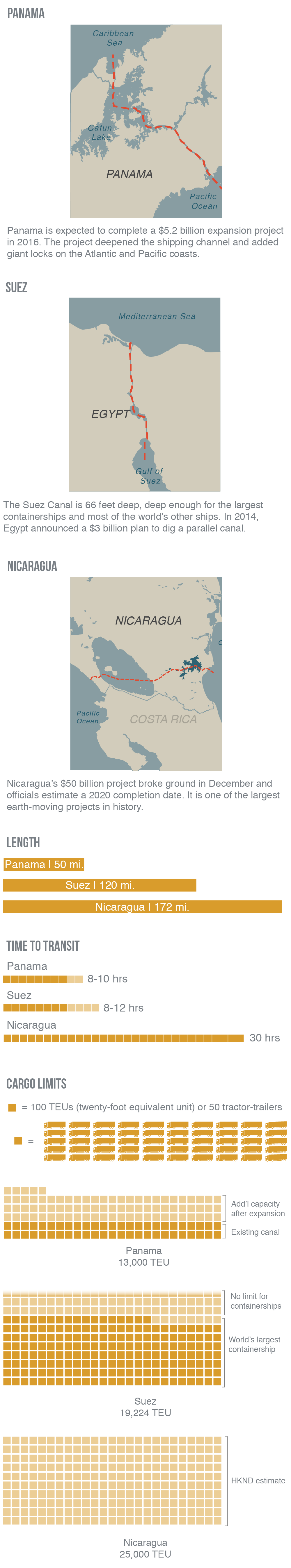

HKND says the Nicaraguan canal is being designed for ships too large to fit through the Panama Canal, but many ships have already switched away from Panama and are "slow steaming" through the Suez Canal. At the same time, Panama is expected to open larger locks next year and Suez has begun construction on a parallel passage.

Regardless of Wang’s ties to Beijing, the Nicaraguan canal, if built, would achieve goals that fall squarely in line with recent Chinese government agenda on two counts.

Internationally, the canal would broaden China’s role in Latin America at a time when Beijing is looking to diversify its energy sources away from traditional sources in the conflict-ridden Middle East. Much of that bid for Latin American hearts and minds has been manifest in China’s signature infrastructure and transportation projects. For example, China’s National Commission of Development and Reform in February met with Peruvian and Brazilian officials to push a $60 million project to build a railway from South America’s Atlantic to Pacific coasts. Xi took a whirlwind tour of Brazil, Argentina, Cuba and Venezuela in July 2014. At a January meeting with his Venezuelan counterpart, Nicolás Maduro, Xi pledged to deepen China’s inroads in the continent to the tune of $500 billion in bilateral trade over the next decade — more than double the present amount.

And domestically the canal would expedite an apparent effort by Beijing to deflate the economic importance of Hong Kong after decades as a so-called window to China.

In early 2013, as Hong Kong’s Occupy Central movement began to organize, Beijing cultivated alternative financial hubs on the mainland, some analysts said, as a threat to Hong Kong officials to either quell dissent or suffer the economic consequences.

“The role of Hong Kong as a conduit between the world and China has been reduced and weakened,” said Baizhu Chen, a professor at the University of Southern California and an expert on China’s economy. “The outside world can directly deal with China.”

In the past couple of years, Chen added, the central government appears to have offered incentive for regional governments to play a bigger role in the country’s finance and trade to counter Hong Kong’s influence.

Countering the Panama Canal would offer a mainland-based alternative to one of Hong Kong’s international assets.

Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing’s company Hutchison Whampoa has a large hand in the Panama Canal, with which the Nicaraguan canal would compete for shipping traffic and tolls. A unit of Hutchison Whampoa, the Panama Ports Co., operates the Panama Canal’s Balboa and Cristobal ports. In October 2014 — only two months before Wang’s HKND Group broke ground in Nicaragua — Panama Ports announced it would invest $110 million in expanding the Balboa port over the course of this year.

Media reports have credited Wang with taking the wind out of Li’s sails with a business deal that would rival Li’s Panama interests.

Wang, for his part, has told the Chinese press that he is not a “successful person" like Li. (Wang is worth $7.7 billion, according to Forbes’ most recenttally, compared with Li’s $33.7 billion.)

Analysts say that Li — who has traditionally been pro-Beijing and has massive interests in the mainland — is falling out of favor with China’s leadership, particularly amid Hong Kong’s unrest.

“I think he’s lost confidence in Beijing’s influence, so they are giving him a hard time as well,” said Gordon Chang, a China analyst and the author of “The Coming Collapse of China.”

In response, Chang said, Li is “investing away from Hong Kong” and moving his assets out of China. In recent years he has furthered his overseas portfolio by making a bid for a huge share of British telecoms. In January he announced plans to merge his two companies — Cheung Kong and Hutchinson Whampoa — and incorporate them not in Hong Kong or China but in the Cayman Islands.

Despite the Nicaraguan canal’s potential to hit Li and Hong Kong in the pocketbook, none of this proves that Beijing is behind the project.

Even Chang, who is extremely critical of China’s leadership, foreign policy and economy, says the project is too fantastical for the likes of Beijing.

“It’s so absurd that I can’t believe the state is behind it,” he said. “You might have somebody trying to curry favor with the state. You might have someone incredibly arrogant.”