Harvest of Fear

Examining the roots of Central African Republic's Séléka rebel movement

Photos by William Daniels / Panos for Al Jazeera America

Edited by Courtney Brooks, Vaughn Wallace

Above: A woman sits by aid supplies being distributed by the Organization of Central African Women in Ndéle.

Published on Monday, December 1, 2014

NDÉLÉ, Central African Republic — One day in September, Ahmed Adam, 23, sat on the ground in the regional capital, Ndélé, and rolled a cigarette. Adam was restless. Earlier that week he returned from the capital, Bangui, about 400 miles away. He was happy to be home. But with no money or means to buy what he needed to restart his life, he said, he was waiting for the U.N.-run demobilization program to begin, when he hoped to collect some cash. “If it works, I’ll be a farmer and work in the fields,” Adam said. “But if it doesn’t work, I’ll return to fight.”

Adam had been fighting since 2010, he said, when he joined the Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (CPJP), a northern rebel group that sought to overthrow the government of François Bozizé since 2008. Adam fought, he said, for the rights of the people in the north. But it was also to avenge a personal insult that he suffered at the hands of Bozizé’s police.

The CPJP believed that Bozizé, an ethnic Gbaya, was corrupt and that he failed to uphold promises to make his government more inclusive of other regions and ethnic groups. In 2012 a faction of the CPJP, along with other rebel groups, foreign mercenaries and local volunteers came together to form the Séléka, which means “alliance” in Sango, the national language. Most but not all the fighters were Muslim like Adam. The movement often recruited impoverished, uneducated men, and Ndélé quickly became a stronghold. The Séléka gathered strength as they went south, and on March 24, 2013, they succeeded in overthrowing Bozizé and installing their own president, Michel Djotodia.

The Séléka’s nine-month hold on power was cataclysmic. Djotodia proved unable to control his ranks of rebels. They raped women, plundered villages and killed hundreds, perhaps thousands of people whom they associated with Bozizé. In the south, nearly everyone was affected in some way. When asked if he ever killed innocent citizens or committed the abuses that so many spoke of, Adam laughed uncomfortably and asked if it was possible to fight and not kill. “But I only killed other soldiers,” he said.

By mid-2013, a mostly Christian group of fighters known as the anti-Balaka, which translates to either “anti-machete” or “anti-bullets,” emerged in rural villages to fight back. The movement was, in part, truly revolutionary: a self-organized militia of young men armed with rudimentary weapons like machetes and homemade rifles. But the anti-Balaka also counted among their ranks former army officers, many of whom remained loyal to Bozizé.

War in the Central African Republic is usually understood abroad as a grinding religious conflict. Of the 4.5 million people who live in the remote, landlocked country, only 15 percent are Muslim; the rest are either Christian or animist. These communities have lived together peacefully for centuries. The latest explosion of violence, though, has succeeded in pitting them against each other. Victims on both sides have suffered, but the minority Muslim population appears to have borne the brunt of it. Two years ago, there were nearly 700,000 Muslims in the country. Now, according to some counts, fewer than 90,000 remain.

Like many wars around the world that are perceived as religious in nature, and where the narrative of communal strife is used by warring sides to fuel hatred, the sectarian aspect of the conflict may be a result of the fertile soil it grew from. A legacy of weak state institutions, the failure of multiple governments to implement promised reforms, competition over natural resources and the unadorned political opportunism of militia leaders gave rise to the fighting and fed it. Religion coils around these dynamics, increasing the pressure.

Militia leaders on both sides use the narrative of religious war to mobilize fighters in the pursuit of their narrow political objectives, said Beni Youkaté, a Guinean man who works in the country as an informal mediator between Séléka and anti-Balaka groups.

“The crisis here is not at all a religious crisis. It’s military, and it’s political. Quite simply, people have their interests in the crisis, and this suits them to use this ideology, this idea that Muslims and Christians can’t get along,” Youkaté said.

The emergence of the anti-Balaka marked a turning point for the country. Many of the fighters conflated the CAR’s entire Muslim population with the Séléka. Soon they adopted a new goal: rid the country of its entire Muslim population. The Séléka, in turn, launched revenge attacks on non-Muslim populations, in particular against Bozizé’s Gbaya. For the first time, the conflict took on a sectarian dimension. At the U.N. headquarters in New York, diplomats spoke of the possibility of genocide.

The anti-Balaka attacked Bangui on Dec. 5, 2013, setting in motion weeks of tit-for-tat attacks between the two communities. Hundreds of bodies piled up in the city’s morgues and mosques. More than 100,000 of Bangui’s Christians fled to the city’s derelict airport, which was protected by French troops, and to other camps. Nearly the entire population of Muslims in the west, including many in the capital, fled north or across the border in “an exodus of historic proportions,” according to Amnesty International.

In September 2013, Djotodia attempted to disband some of the Séléka, and Adam, along with thousands of other fighters, was disarmed and forcefully billeted into a crowded, run-down military camp in Bangui. The plan was to integrate them into a new, professionalized army, but it never happened, and he languished there for months. “They just gave us some food, barely enough manioc”— a staple food, like a potato, that is eaten throughout Africa — “for the entire week and occasionally some sardines,” he said. “Life was really hard.”

Faced with increasing regional pressure over his inability to stem the violence, Djotodia resigned in January of this year and fled to Benin. A week after his departure, the CAR’s interim lawmaking body, the National Transitional Council, appointed the mayor of Bangui, Catherine Samba-Panza, as the interim president. As the country descended further into anarchy, additional peacekeepers from the African Union, France and European Union were deployed. Though they were able to prevent large-scale slaughter, the violence did not stop. At least 400,000 people have been displaced by the fighting, and more than half the population is in need of humanitarian assistance. Thousands have died in the fighting.

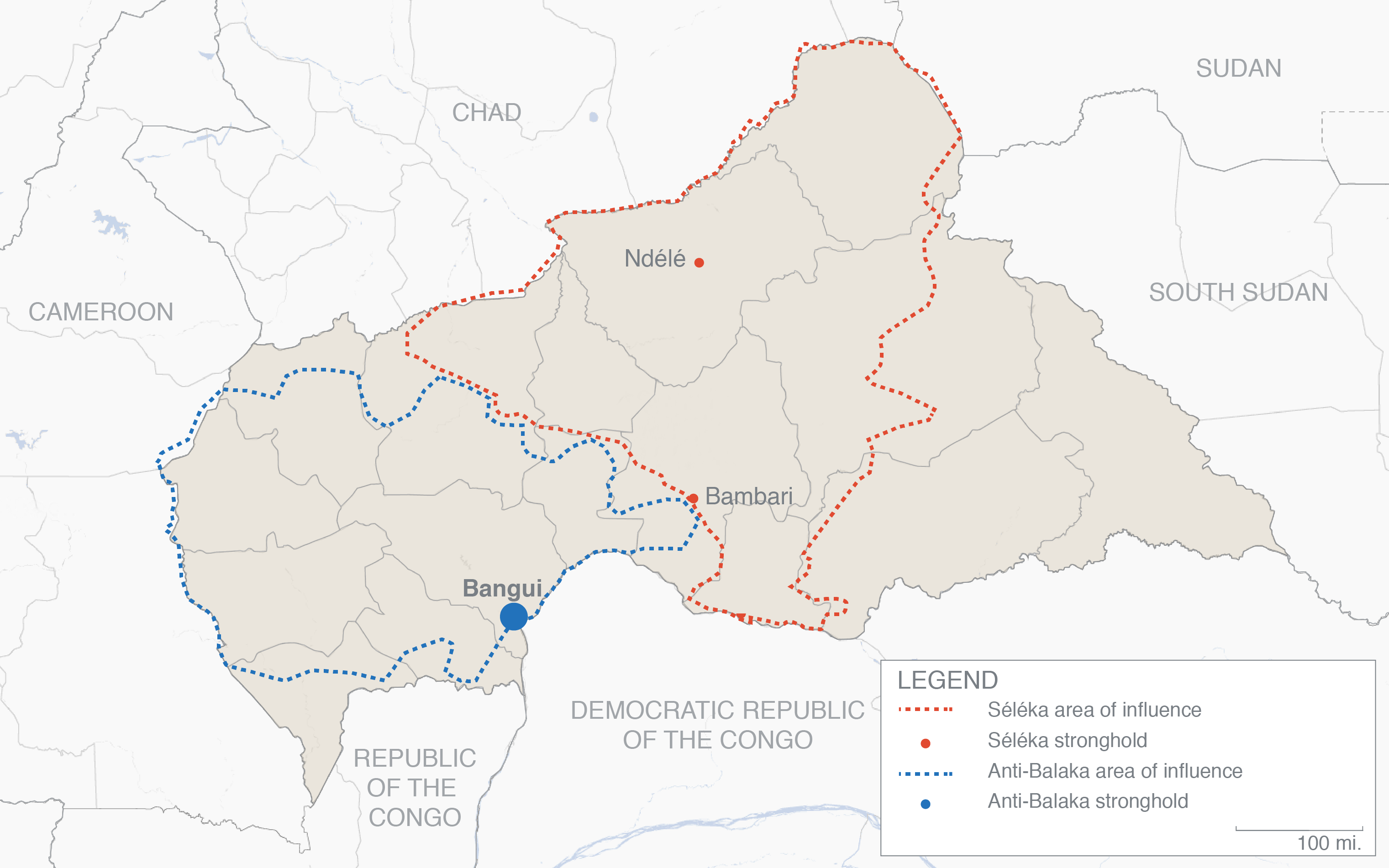

The country is now divided, de facto partitioned into zones where militias hold total sway. Anti-Balaka militias control the west. The Séléka have fled north and established a new headquarters in Bambari, 300 miles from the capital. International forces, meanwhile, back an interim government in Bangui that has little influence over the rest of the country. A cease-fire signed in July has had little effect on the ground. The Central African Republic remains flush with weapons, a tinderbox ready to reignite, with fighters like Adam waiting to see what the future will hold.

Ndélé, in the north of the Central African Republic, lies at the crossroads of historical, cultural and commercial routes that link Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, Sudan and South Sudan. Though it is the capital of the prefecture, it remains a quiet town of about 15,000 people. The streets are unpaved and lined with mango and acacia trees. In 1905, when the French established the colony of Ouabangui-Chari, as the Central African Republic was then known, Ndélé had been in existence as a political entity for years, under the authority of a sultan. Since then, the region has maintained a distinct identity from the south. Ibrahim Senoussi Kamoun, the current sultan, remains an important authority. Islam is the dominant religion in the north, compared with animism and Christianity in the rest of the country. In addition to tribal languages, Arabic is spoken more commonly than French or Sango — even by the town’s Christian minority.

When Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries and what was then the nucleus of the Séléka arrived in Ndélé in December 2012, they looted most public buildings, including schools, the mayor’s office and the police department. In the former police chief’s headquarters, ash lines the floor a foot deep; buried in it was a French colonial newspaper from 1938, intact, announcing admissions results to L’Ecole Nationale de la France d’Outre Mer. Despite this pillage, the town and its surrounding region have avoided the worst of the country’s violence.

Kamoun sat in his courtyard near the center of town, wearing a white jalabiya (a traditional Arabic robe) and a kufi (a rounded cap). He has been sultan only since May, when he took over from his father, who died of cancer. Since the Séléka arrived, Kamoun said, the state has been absent in Ndélé, so he has stepped in as a traditional authority, holding weekly meetings with community leaders to discuss any simmering disputes. It is a point of pride that they have largely managed to avoid the ethnic tensions elsewhere in the country. “Everything that happened in Bangui needs to stay in Bangui,” he said.

Kamoun justified the rebellion against Bangui in terms that were echoed by other Ndélé residents. The government, he said, has abandoned the north since independence and withheld development funds for infrastructure, schools and health care. Southerners and non-Muslims elsewhere in the country often referred to ethnic groups in the north, especially those with family ties across the border in Chad, as foreigners. Despite a number of earlier rebellions — and promises by Bozizé to invest in northern communities’ development — little was ever implemented. “Since independence, we live apart,” he said. “The rebellion that formed here was to defend the rights of the people of the northeast.”

Kamoun’s complaints, though strident posturing, held some grains of truth. Many of Ndélé’s public services have fallen into disrepair and are operated by foreign humanitarian agencies. The International Committee of the Red Cross operates the town’s water system, providing potable water for a few hours each day. The municipal hospital, which serves 50,000 people, is almost entirely staffed by the international aid group Doctors Without Borders.

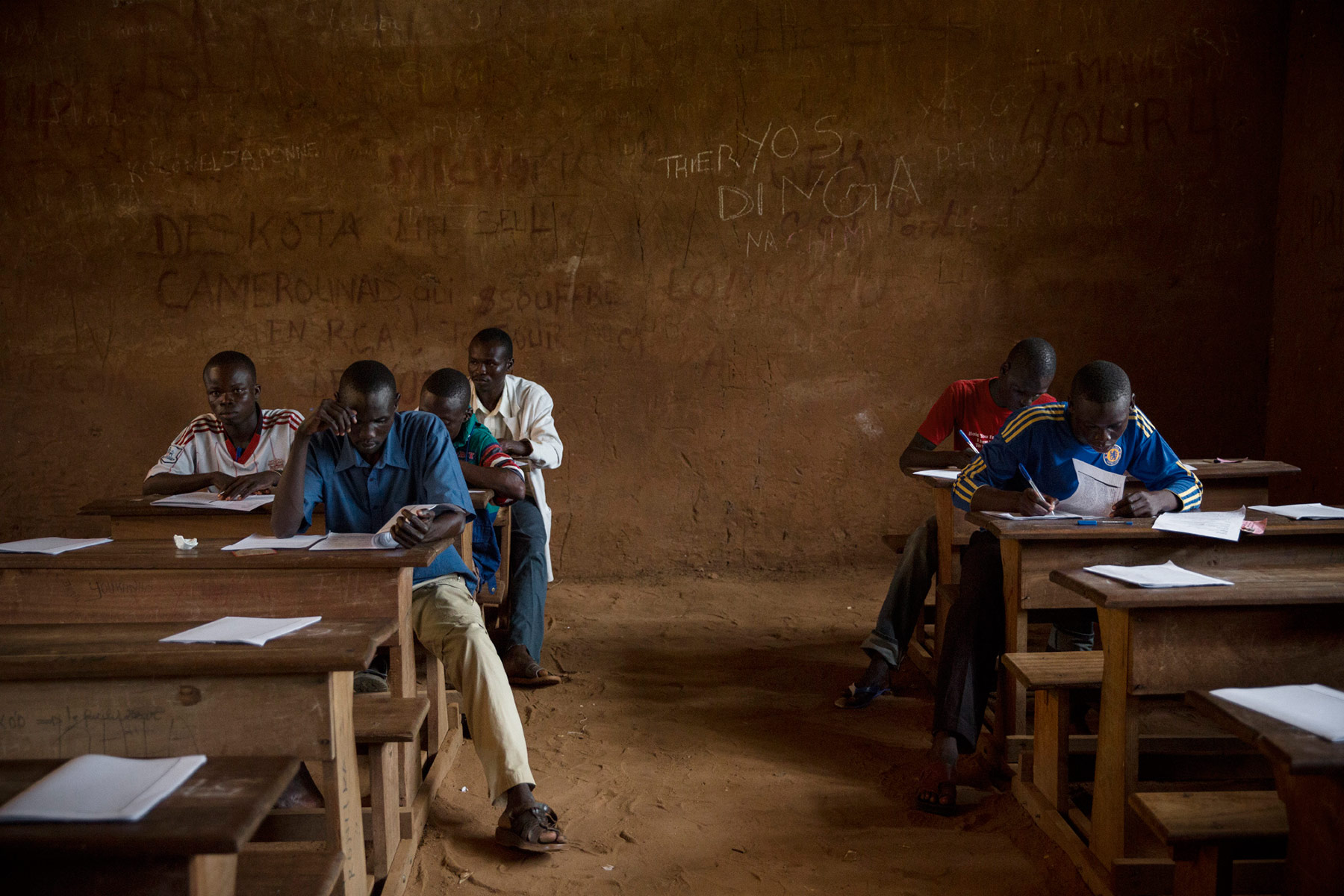

Ndélé’s only high school lies partly in ruins on the outskirts of town. On a school day in September, a dozen teenagers were taking the bac (a test based on the French exam given at the end of secondary school) in one of only two functional classrooms. The other buildings, half-crumbled mud-brick structures with tin ceilings, sat empty, with no doors, desks or equipment.

Idriss Assane, an English teacher at the school, said that given the lack of choices near Ndélé, residents often sent their kids to elementary and high school in neighboring Chad or Sudan. It was nearly impossible to hire teachers willing to work in Ndélé, so the majority of instructors were pulled from the parents of the student body. “Many teachers who are assigned here just don’t come,” said Assane. “It’s too far.”

However, Assane said that most of the damage at the school occurred after the Séléka invasion. When the militias first arrived, he said, dozens of ragged fighters camped out in the courtyard and used its entire library as firewood. This academic year, the school’s 749 students shared only one ruler, one compass and one framing square — all that remained from before the invasion. Assane questioned why the Séléka would loot the schools when they complained of marginalization and the need for more investment in the north.

Adam decided to join the rebellion in 2010, driven by desperation. He was biking from Ndélé to a town in the south with about $200 in cash and $150 worth of smoked fish, which he hoped to sell at a market. He came upon a police checkpoint manned by officers from the capital. As an uneducated ethnic Rounga, a minority group from the north, Adam didn’t speak Sango or French. The police, thinking he was a foreigner, detained him for much of the day and then confiscated his bike and fish. That was everything he owned. After he was released, he returned to Ndélé and immediately joined the CPJP. “When they took all my stuff, I was so angry,” he said. “I wanted to show them that I was a man.”

On the other side of Ndélé, a ragtag group of 35 child soldiers and other young enlistees occupied the city’s looted police office. They sat around the gutted building in makeshift, tattered uniforms, collecting 20 cents from every motorcycle driver who passed — earnings they used to buy food and cigarettes. Almost all the fighters recalled the inception of their armed struggle, like Adam’s, as a story of personal grievance against a society that left them behind or took from them unjustly.

Samira Fizan, their leader, said both her parents died from injuries sustained while political prisoners under Bozizé. Fizan, 23, joined the CPJP as a minor and then the Séléka as a member of the presidential guard under Djotodia. Adam Yakoub, 20, said anti-Balaka fighters hacked his mother and 10-year-old brother to death with machetes in the early stages of the fighting. Yakoub was at the Chadian Embassy in Bangui at the time, applying for a visa to flee the country; he stayed and joined the rebellion. “I wanted revenge,” he said.

The seeds of revolution and the infrastructure to grow it were planted in Ndélé while these young rebels were children. Ndélé is in one of the most tumultuous regions in the world, bordering violent conflicts in Chad, Darfur and South Sudan. Guns pass readily through the countries’ porous borders — and so do ideas. Experts say the rebellion in Darfur, beginning in 2003, spread seeds of revolt across the region, scattering notions of insurrection into areas that were fertile for revolution.

“The rebellions in the north were basically something that came up because of the war in Darfur,” said Roland Marchal, a senior researcher at political science university L’Institut d’Etudes Politiques in Paris. “People got ideas, contacts, weapons and ammunition from there. Even the discourse on marginalization came from Darfur.”

The Central African Republic is one of the poorest and least developed countries in the world, ranked 180th of 187 countries on the 2013 U.N. Development Program human development index. Illiteracy and unemployment is high and perhaps higher in the north after years of neglect. “They take up arms because it’s an easy solution,” said Kassara Aziza, the president of the Association of Central African Women.

A security meeting is held every week at what used to be the mayor’s office in Ndélé. In active war zones, the purpose of such a meeting is to maintain open communication between armed groups and civilians. In Ndélé, the meeting usually includes members of the Séléka, French peacekeepers who are stationed nearby and humanitarian agencies.

During one recent gathering, Ibrahim Moussa — an elderly man who, though he said he hasn’t been paid in years, is still acting as the district administrator of Ndélé — sat hunched over a large wooden desk. He ran through the latest developments: The hospital was experiencing a shortage of blood, and blood donations were needed; in an effort to build confidence, French troops recently began mixed patrols with the Séléka, and it was considered successful; fighters were once again encouraged to stop openly carrying weapons in town. The conversation was cordial, but the tone shifted when the mayor brought up the recent return of demobilized fighters like Adam.

Under the mandate of the CAR’s new peacekeeping mission, which was launched on Sept. 15, the U.N. is tasked with supporting the government in disarming, demobilizing and reintegrating ex-combatants. This involves providing them with some money and job training. Unemployed, impatient ex-rebels are a source of instability anywhere in the world, so the program is an integral part of peace building. But the process had yet to begin, even as Adam and at least 100 other former fighters arrived back in town. “It makes no sense to have them come back here,” said Moussa. “They took up arms, and nothing has changed. They have a family, but still nothing.”

Across town from the meeting, Adam reflected on his years as a fighter. He hoped to return to his birthplace in a village just outside Ndélé as soon as possible. Lighting a cigarette, he said that if the demobilization process finally started, he would use the money to buy farming equipment and return to what he was doing before: growing peanuts in his field and working as a laborer for neighbors when work was available. For Adam, demobilization would also be a formal acknowledgement of his years in combat and allow him to close a chapter in his life with his head held high — and his anger appeased. But so far, the signs were not encouraging.

“When they took everything, I had nothing,” Adam said, speaking of the bike and fish confiscated by state police years earlier. But after fighting with the CPJP and the Séléka, he said, “I still have nothing.”

Benedict Moran reported from the Central African Republic on a grant from the International Reporting Project (IRP), an independent journalism program based in Washington D.C.