The hidden scars of Chicago's guns

PTSD affects many victims of violent crime in the city, but few seek help

Photos by Carlos Javier Ortiz for Al Jazeera America

Edited by Matt Williams, Christopher Shay, Mark Rykoff

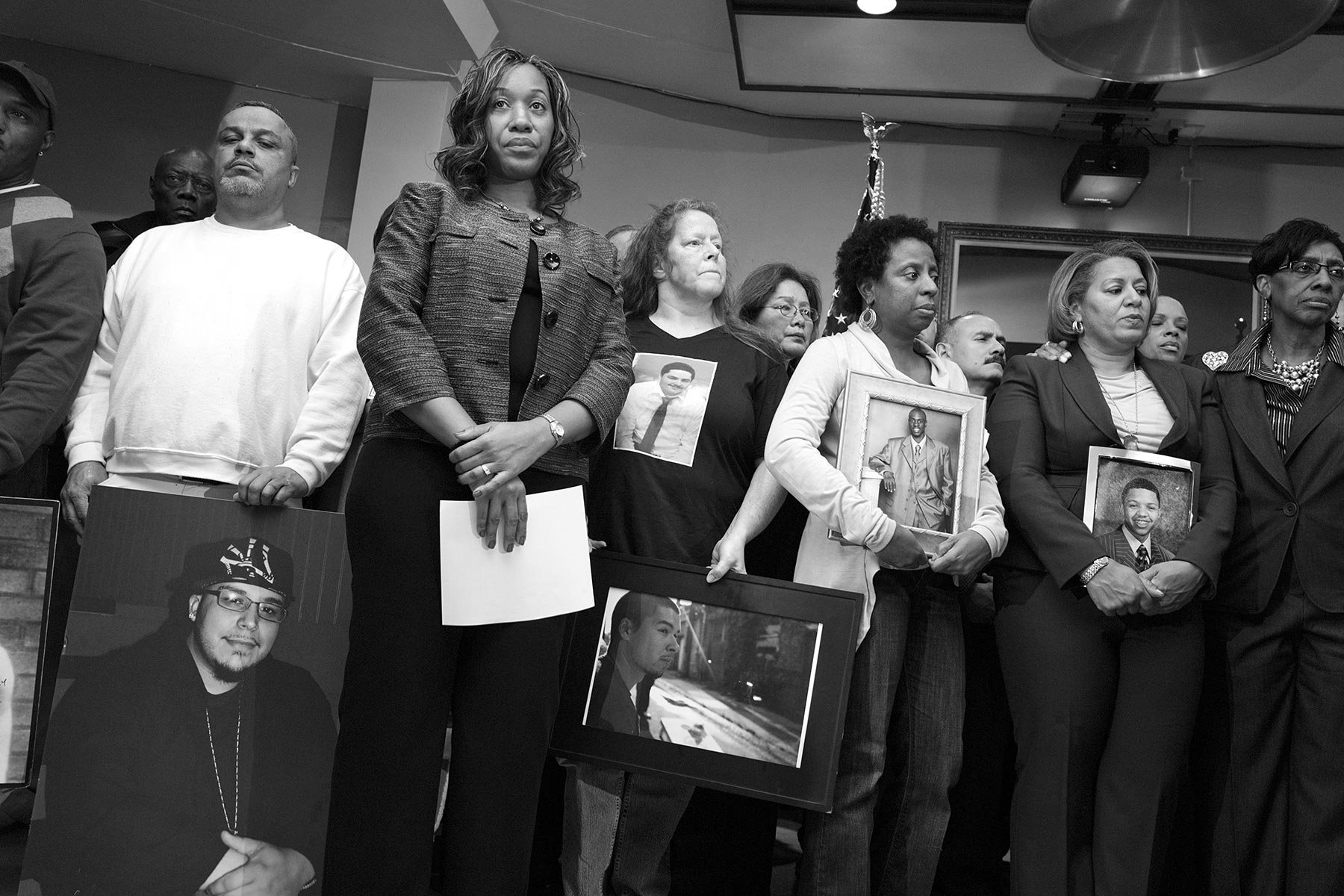

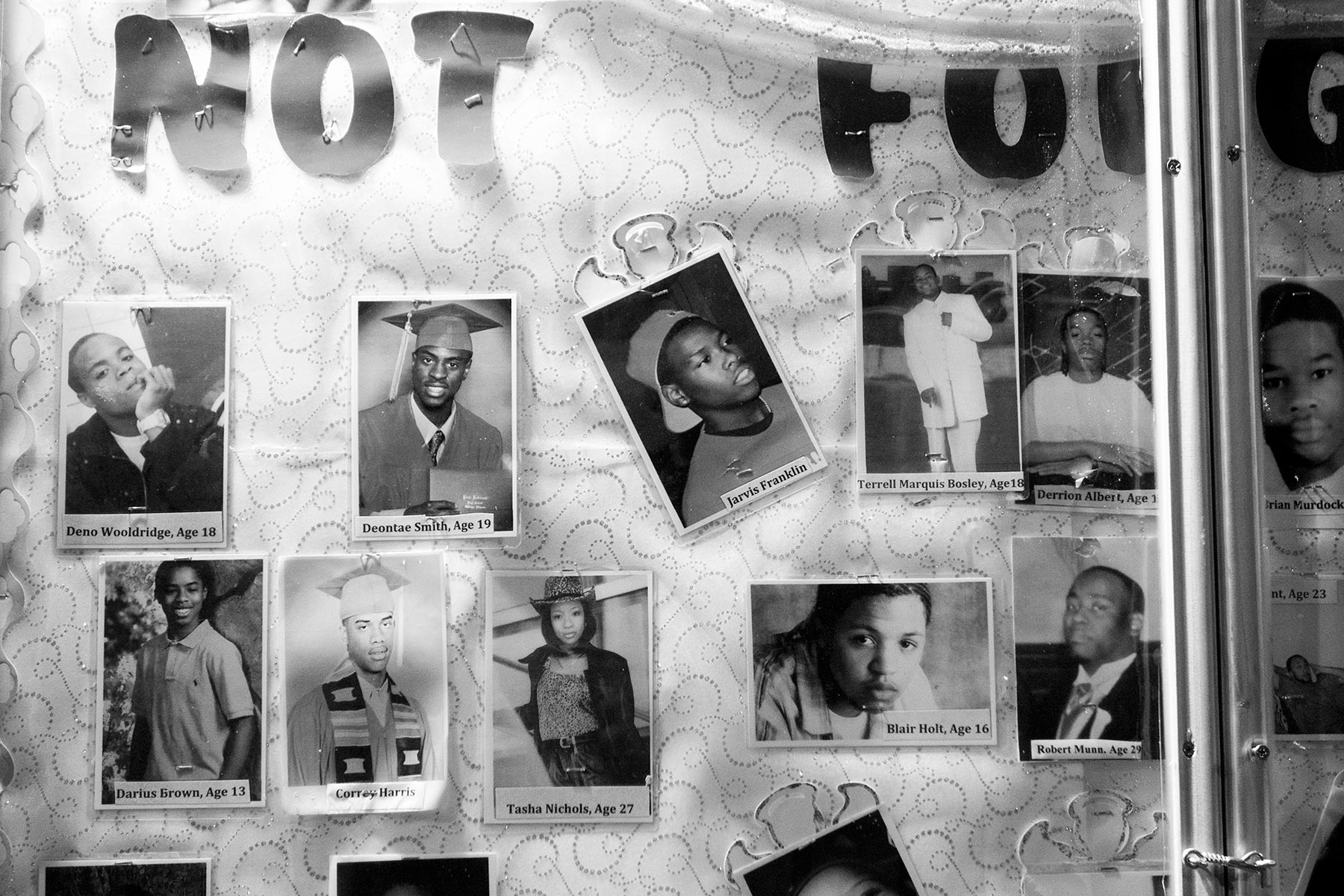

Pamela Bosley, above in black, and her husband Tommie, lost their 18-year-old son to gun violence in 2006.

Published on Thursday, November 20, 2014

The physical scars of the victims of Chicago’s gun violence are all too visible. The mental ones can be harder to detect.

With about 2,000 shootings and more than 300 murders in the city each year, the strain on those who survive — victims and perpetrators — can be great, but not all seek help in a city with dwindling resources for mental health services.

“Most people who experience trauma are not going to identify themselves as mental health patients and seek treatment,” said Dr. Stevan Weine, a psychiatrist and professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago who specializes in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“You have to find them where they’re at and try to work with them to build their coping strategies,” he added.

A study of trauma patients at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital in 2011 found that more than 40 percent screened positive for symptoms of PTSD, which can include persistent feelings of anxiety, depression, nightmares and expressions of anger. For gunshot victims the percentage was even higher. Many who suffer don’t know they have an ailment at all or that it can be treated.

But attempts to expand PTSD screenings at local public hospitals have hit roadblocks. At Cook County Hospital, which treats a steady stream of victims of gun violence, a limited budget has prevented the taxpayer-funded hospital from expanding its PTSD screening program.

Although administrators supported the idea, they told one trauma surgeon who wanted $200,000 for a screening program to seek funding from outside the hospital. PTSD resources are stretched thin, with fewer than 10 staffers responsible for as many as 5,000 patients, according to a ProPublica report.

The lack of available funding at Cook County is a problem across the city that has not been helped by shrinking state funds. Since 2009, Illinois has slashed its mental health funding by more than $240 million, according to a National Alliance for Mental Health study.

Amid those budget cuts, Chicago closed six of its 12 mental health clinics in 2012, many of which were in high-crime areas, leading to overcrowding and long travel times for patients.

Despite offers of treatment at other clinics, patients received less attention and had to travel farther to receive care. At a city council hearing this summer, advocates for reopening the centers said cuts forced more than 2,000 patients out of about 5,000 to end their treatment, according to The Chicago Tribune.

Thandiwe Gobledale is among those tasked with counseling those affected by gun violence. As a hospital chaplain at Advocate Christ Medical Center, she is often the first to provide comfort.

She described counseling services’ accessibility issues as a major hurdle to mental recovery. “Fear, grief and anger are often raised by being shot or having a loved one shot,” she said. “There are not enough resources.”

And there is another problem. Many people don’t know that support services, often provided by local community groups, even exist.

For the children in one family who saw a shooting, Gobledale pointed to help, but it’s nearly impossible to know if anything came of it. “Identifying the need and ensuring that someone follows up appropriately can be difficult,” she said.

People who have had their lives permanently changed by a shooting need an opportunity to vent, she said, adding that this is something many young people don’t get on the street, where peers can interpret expressions of sadness as signs of weakness.

“People need places where they can freely express the emotional roller coaster that can follow being shot or having a family member or friend shot. Especially pertinent may be questions of how to go on with life,” she said.

And without such support, some buckle in the aftermath of a shooting. Pamela Bosley lost her 18-year-old son, Terrell, to gun violence in 2006. In the aftermath, she believes, she suffered from PTSD.

“The pain was so bad, I tried to take my life,” she said. Struggling to overcome the grief, Bosley, 42, went into a closed garage and turned on the car’s engine, with the intention of suffocating on exhaust fumes.

“They say you die peacefully,” she said.

Bosley backed out on that occasion, she said, mindful of the effects it would have on her other two sons.

But on the first anniversary of Terrell’s death, she swallowed what she thought was an overdose of sedatives, hoping to die. Instead she just slept and woke to bright morning sunlight, she recalled.

More than eight years after her son’s death, Bosley spoke to Al Jazeera in a meeting room in the basement of St. Sabina Church, which has become a focal point for anti-violence activism on Chicago’s South Side.

She said that after her son’s death, she couldn’t sleep for a year. The grief came in waves. At one moment, she would be calm; the next, she would burst into tears.

After her suicide attempt with the pills, she hasn’t tried again. Now she counsels children at St. Sabina — a school, gym and community center affiliated with the local Catholic parish.

For the last three years, Bosley has worked as St. Sabina’s violence prevention manager, working with youths ages 14 to 21, all of whom have lost a loved one to violence.

She says that therapeutic resources for children are almost nowhere to be found in her community. “The children have nobody to talk to,” she said. “So they build up all this anger.”

Young people affected by gun violence do share their feelings, but only if they have the chance, Bosley said. “Once you get them to feel comfortable with you, they express their pains and how they can’t function in school,” she said.

“It’s not that they don’t understand the assignment, but they can’t concentrate because of what’s going on in their mind. They’re remembering their brother or another loved one dying.”

Stigma against seeking mental health treatment is another obstacle for those affected by gun violence. Many young people don’t want to appear weak to their friends or their foes. And they don’t want to bear the slur of being “crazy,” Bosley said.

Aside from the innocent victims, the perpetrators of gun violence also need mental health counseling, experts say.

“We had people tell us that we’d see a lot of people who were gang bangers and they wouldn’t develop PTSD because they were already hardened to that kind of life,” Grant Marshall, a behavioral scientist, told ProPublica. “We didn’t find that to be the case at all. People in gangs were just as likely as anyone else to develop PTSD.”

Weine said that frontline strategies for police and counselors involve officers immediately intervening after violence and talk therapy experts caring for the emotional state of victims or witnesses to violence — all of whom, he said, are at risk of developing PTSD.

“Let’s say a kid witnessed a murder,” he said. “There’s a police officer with the kid. We’re not even talking about them spending any more time than they already would, but there’d be a couple of things they could say or do to let that child have a better chance.”

The remedy could starts with police assessing the psychological state of gun violence victims and referring them to support services. One task for responders is to make victims aware that they might have a psychological injury that accompanies the physical trauma they endured or saw, experts say.

Weine pointed to the Yale University’s Child Development–Community Policing Program as an example of how police can better respond to the needs of victims by training officers to understand the invisible, psychological trauma of violent events.

Participating in sports, seeking help in communities of faith, engaging in creative expression and joining support groups are solid coping strategies.

But for Weine, a specialist in PTSD among refugee communities, the mental health provisions for Chicagoans is wanting.

“If you’re a refugee coming from war and you’re resettled in the U.S., you have access to special mental health services to treat PTSD. But if you’re living in Chicago on the South Side or the West Side and you’ve been exposed to violence, you don’t have such an opportunity. Those programs don’t exist,” he said.