‘If I get shot, I won't be caring’

Chicago youths numbed to cycle of violence

Photos by Carlos Javier Ortiz for Al Jazeera America

Edited by Matt Williams, Christopher Shay, Mark Rykoff

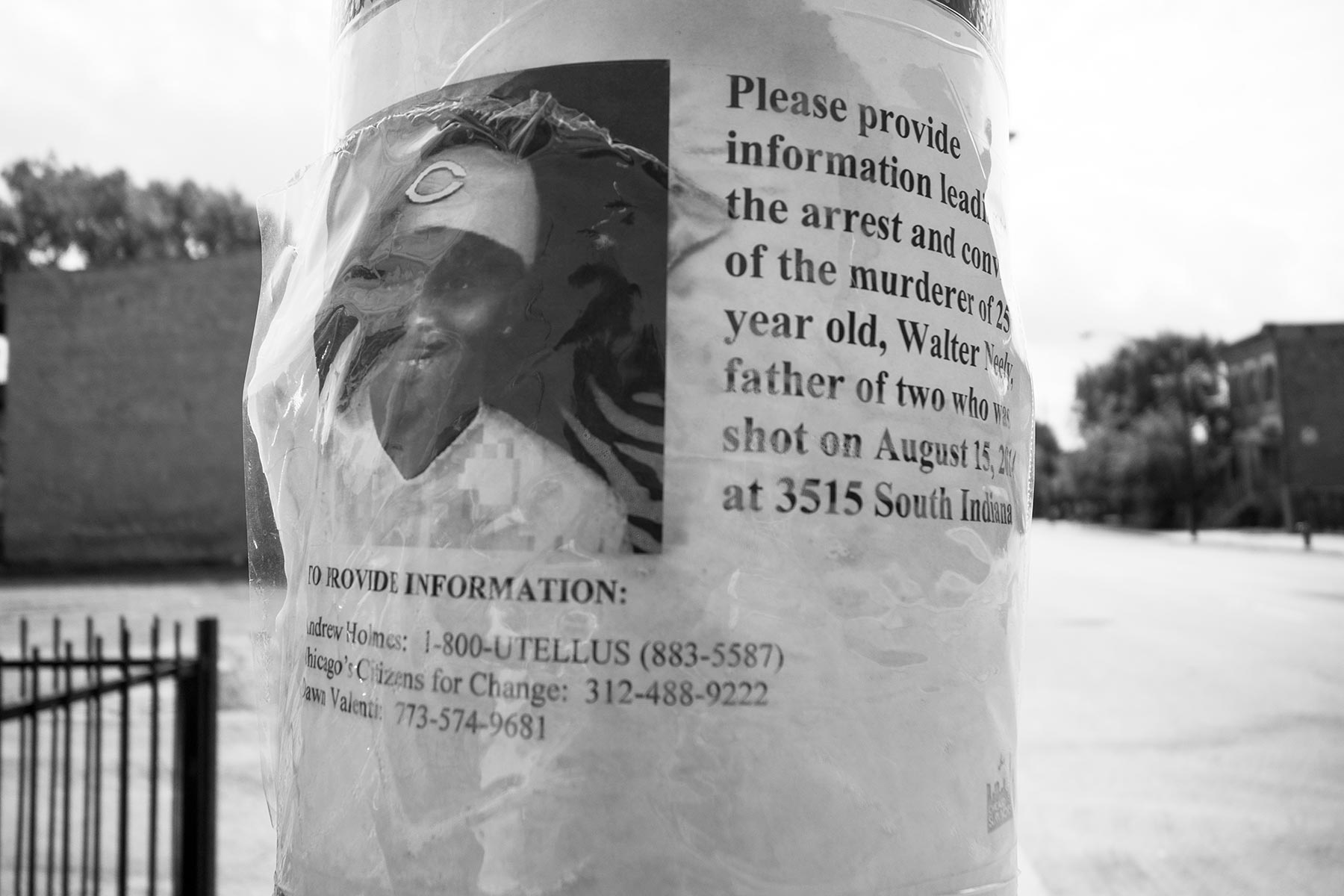

A memorial to Walter Neely 25, who was fatally shot about a block from Chicago Police Headquarters in August 2014.

Published on Friday November 21, 2014

“Write this down: RIP — Revenge. Is. Promised.”

The threat, issued by a young man in his mid-teens, illustrated a sentiment seemingly shared by the gaggle of youths gathered on a sidewalk in a quiet part of the Roseland neighborhood in Chicago’s South Side. The warning as to what would befall anyone who harmed one of his friends reveals the frightening logic behind an unforgiving cycle of violence.

The boy’s promise of retaliation may have just been youthful bravado, but in one of the city’s poorest neighborhood — one dogged by successions of shootings and reprisals — such attitudes have consequences. Located far down Chicago’s South Side, past 100th Street, Roseland is part of a swath of the city locals dub the Wild Hundreds because of the high violent crime rate.

Of the more than 340 people who have been murdered in Chicago so far this year, most of them are under the age of 25, and the majority died from gunshot wounds. Some are in their teens, some younger. Nine-year-old Antonio Smith — the youngest victim in Chicago this year — was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The vast majority of Chicago’s young people do not commit gun crimes or belong to gangs. But around Chicago’s South Side, it was hard to find people of high school or college age who had not been personally affected by violence.

All the men and boys who spoke to Al Jazeera knew someone who had been shot or killed, many of them in the last year. One 20-year-old said he couldn’t count how many funerals he’d been to in his life.

Tyreece Stagger, 16, lost a cousin to gang violence. “I was depressed. It makes me angry. Makes me want to turn up for them,” he said, “It’s like he said. ‘RIP. Revenge is promised.’”

“I just feel like if I do get shot, I wont be caring. I take risks every day, every time I come outside, going to jail, getting shot, all that,” he added.

As he spoke, a white car rolled past the group, grabbing their attention. A few minutes after the sedan appeared, a police car drove down the street. An officer took to a loudspeaker to tell the boys to get off the street. They complied but cursed the Chicago Police Department as they did.

“The police is crooked as hell,” said Damen Jones, 20.

Another young man, who declined to be identified, said, “If you run, they shoot you.”

The sedan rolled past again. The people in it turned out to be from a rival group, the kids said. Exposed on the sidewalk, with their backs to an empty grassy lot, the clique retreated to the safety of a snack stand on an older couple’s porch.

“If they come through this block more than three times, you know you’ve got to leave the scene. Unless you got a gun,” Stagger said as he walked away.

Before the arrival of the car cleared him and his and his friends off the sidewalk, Jones described Chicago’s South Side as a “jungle.”

“We just trying to be the lions around this bitch,” he said. “We ain’t got no choice but to adapt. You hear me? Each and every day. We ain’t running from nobody.”

“If that means I gotta protect myself, I gotta protect myself. At any point in time you can get got,” Jones said.

He said media exaggerate the role of gangs in the city’s violence. Rather, young people hang out in groups of friends who watch one another’s backs.

“All the gun violence, we do it for each other,” he said.

Eric Wilkins knows where the cycle of violence can take Chicago’s youths. In 1999 the then–drug dealer was shot.

Partially paralyzed by the bullet, Wilkins, 40, now works as an anti-violence activist, hoping to steer young people away from Chicago’s gangs.

“These are good kids. These are my little guys, and they’re full of pain,” he said.

His organization, Broken Winggz, counsels and guides young men such as those Al Jazeera spoke to in Roseland.

He blames a lack of jobs and role models and the closing down of schools and nonschool activities for the difficulties young people face.

Broken Winggz mentors kids to keep them away from violence, and it also deals with the aftermath of gun crime — helping young men paralyzed by gunshots rebuild their lives.

Breaking the cycle of violence is a crucial but difficult endeavor. “How can you convince someone not to retaliate, and they’ve been shot, and they almost died? It’s a challenge,” Wilkins said. “You have to go through it to really understand it. I think a person who has been shot can talk to another person better than someone who hasn’t.”

Defying his severe spinal cord injury, Wilkins — who taught himself to walk again, with the use of leg braces — paced haltingly among the young men.

He lives nearby, and they seem at ease around him and showed him respect. When he told them to clean up chip packages and candy wrappers from the stoop where they were sitting, they did so at once without complaint.

He explained that, as a mentor, he is trying to provide the support that they may not be getting at home. Some have been left to “raise themselves,” he explained.

Nearby, a young man licked clean the greasy inside of an empty chip bag. “For them, that might be breakfast, lunch and dinner,” Wilkins said.

For others who, like Wilkins, have survived Chicago’s gun violence but paid the price of a lifelong injury, the youthful utterances of revenge cover for feelings of fragility and fear.

“They don’t mean that, it’s all a facade,” said Arnelious Sneed.

Sneed, a 32-year-old South Side resident, is a living example of the cost of getting involved with drugs and gangs in the city. He hasn’t been able to walk since May 2013 — a casualty of the cycle of violence.

“I got shot five times,” he explained.

The attack, at 68th and Damon Ave. severed his spinal cord at his T4 vertebra, paralyzing him from the waist down. “I died and came back to life,” he said, remembering a white light and a ride to the hospital. “They brought me back to life.”

When he woke up, doctors told him what happened. He tried to move his legs, but he couldn’t. A breathing tube down his throat prevented him from speaking.

“A tear came to my eye,” he said.

Sneed represents the kind of victim of gun violence whose struggles very rarely make the news, but it is a story that could dispel the misplaced glamour of street violence that some young people have.

A former drug dealer, him had been incarcerated five times — once for two and a half years, on gun and drug charges — by the time of the incident that saw him lose the power of his legs.

Many people wouldn’t consider him an innocent victim. Some less charitable people might even say he got what he deserves. But gun violence in Chicago torments the innocent and guilty alike, and the effects are the same.

Sneed talks of sadness, frustration and the departure of loved ones and friends. “I had a girlfriend before I got shot,” he said. “She was with me for a minute before it went south. They see what they got to do for you.”

“I’m not thinking about no girl,” he said. “I can’t do what I need to be doing with her. Another man can do that.”

Today Sneed gets around with a wheelchair and can’t get down the steps from his porch without someone to help him. His leg muscles have withered. Knee-length basketball shorts expose his sticklike shins.

He, like the boys hanging out in Roseland, also gets guidance from Wilkins. Although they certainly see the paralyzed in wheelchairs on the street, Chicago’s young men who promise revenge rarely get the chance to hear how grim life can be for a victim like Sneed.

“‘If I get shot, I get shot’ — I would never make that statement out of my mouth. Ever,” he said.