Canal 'will destroy we'

Bangkukuk residents worry canal will be final blow to their language and traditional culture

A deep divide

Part four of a five-part series examining the impact of the Nicaragua canal.

The president of this remote indigenous village on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua has just returned from planting beans in the fields. Though casually dressed in a fresh white undershirt and jeans, it is clear he is deeply worried.

“Here we pass many things,” said Carlos Wilson Bilis, 31, speaking in the Creole English characteristic of the Miskito Coast of Nicaragua. “We pass the war, we pass the hurricane. Many things we pass here. And the government didn’t help us. Now he want to come and destroy us.”

This destruction, according to Wilson, would be the price Bangkukuk pays for the Nicaraguan canal, a $50 billion infrastructure project that would compete with the Panama Canal and allow passage of enormous container ships that can individually carry cargo equivalent to more than 12,000 tractor-trailers.

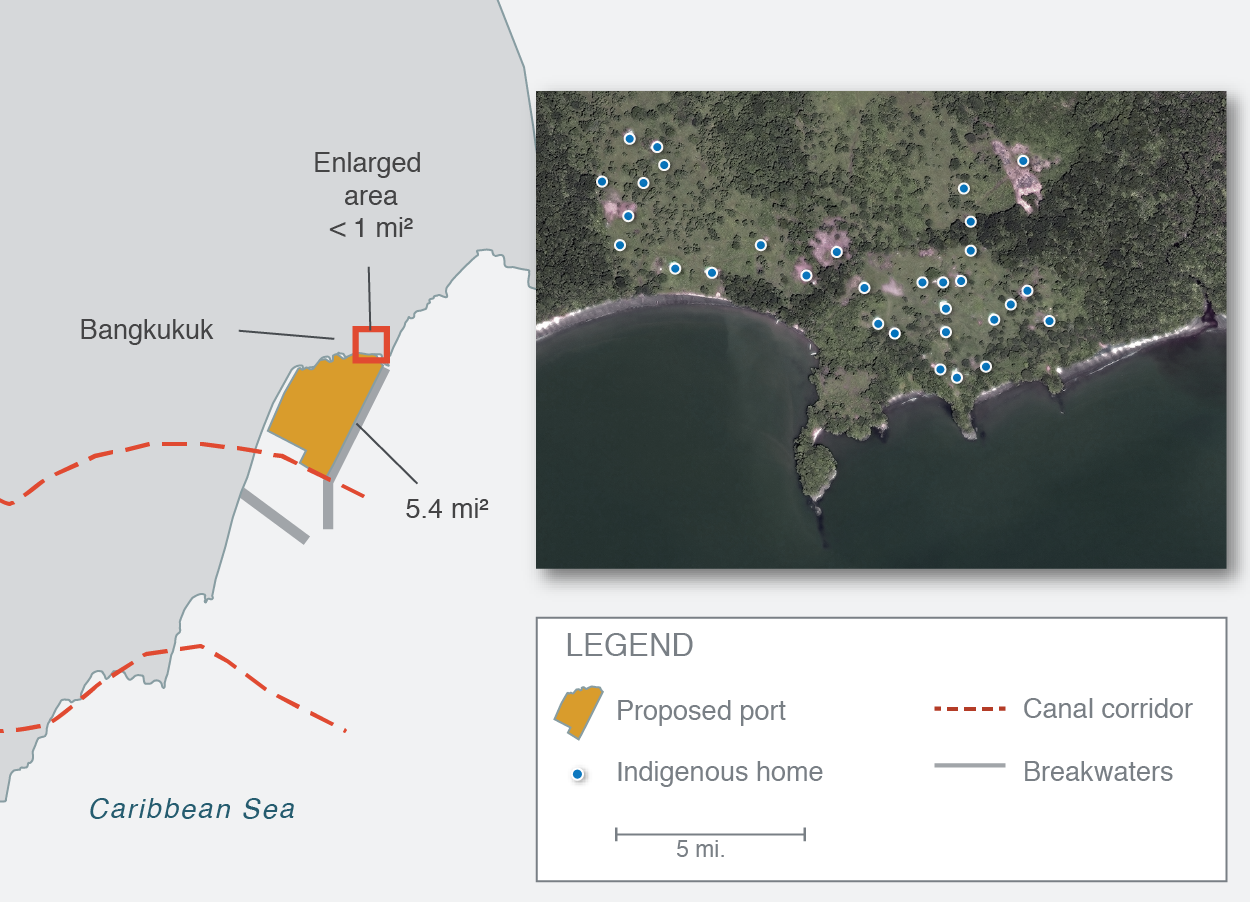

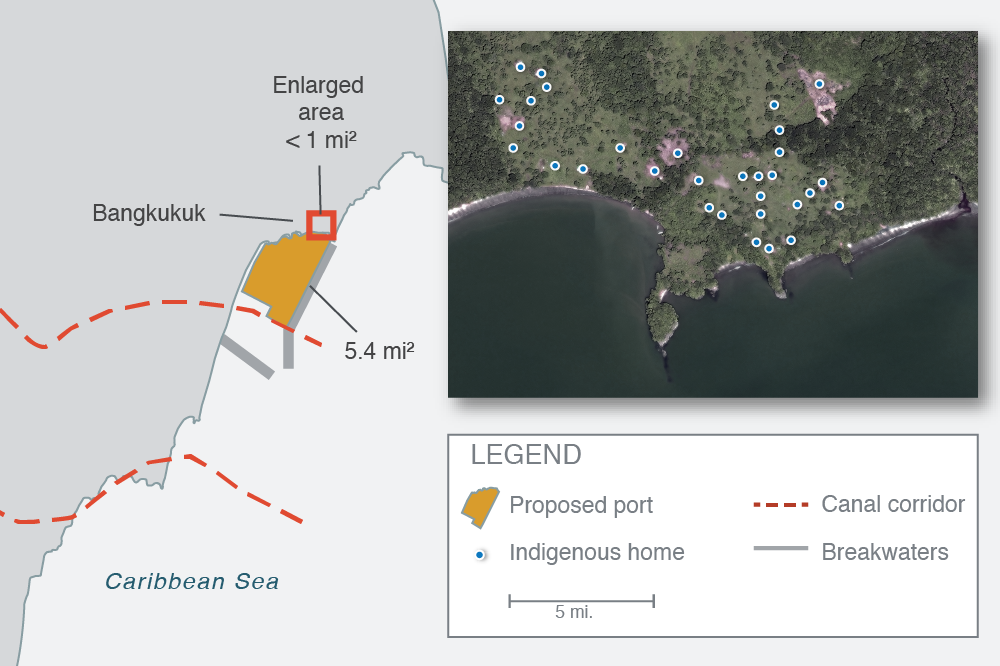

According to HKND, the Chinese holding company granted a 50-year concession by the Nicaraguan government to build the canal and its related projects, the 172-mile route will start along the Pacific shoreline in Brito, cut through Lake Nicaragua and the interior of the country, and cross autonomous indigenous territory before meeting the Atlantic Ocean at Punta Gorda, just south of Bangkukuk Taik. A deep-water port will be constructed in Bangkukuk that extends into the neighboring communities of Monkey Point and Wiring Cay.

Bangkukuk Taik (as it’s known in Rama, Punta Águila is its Spanish name) is one of nine indigenous and Afrodescendent communities that make up Nicaragua’s Rama-Kriol Territory. Its 140 residents (according to a mid-2000s census) live entirely off the land — hunting, fishing and farming yucca, bananas, sugar cane, beans, corn and other crops. They use wood from their trees to construct their homes and canoes. There are no cars, paved roads, running water, stores, or Internet. While Creole English is the common language, residents also speak some Spanish, and the village is home to the last fluent speakers of the Rama language.

For decades the Rama have been threatened by the eastern migration of the mestizos, Nicaragua’s majority ethnicity, who have been cutting down forests in the indigenous territory to build cattle ranches. Now the Rama worry this new threat — what the president of Bangkukuk called “the millionaire monster” — will force Rama people off the little land they have left, and scatter the last remaining speakers of their traditional language.

“We’re trying to do what we can to promote it,” said Barbara Assadi, an ethno-linguist with the Rama Language Project, which since the 1980s has been working to document and “grow back” the Rama language. “It is making a little headway if you at least have children learning words and phrases in school, but if that community is dispersed that’s the end of it.”

Negotiating land rights

- This January 2015 letter from the Nicaraguan attorney general to the president of the Rama-Kriol Territorial Government seeks a permanent lease for the canal and sub-projects, and says land will not be confiscated.

- The Rama-Kriol Territorial Government submitted these requirements to the central government of Nicaragua defining how the canal consultation must be done within their indigenous territory.

According to a complaint filed in June 2014 to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights by indigenous governments of Nicaragua's South Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAS), 40 percent of the proposed route passes through indigenous and Afrodescendent territory. Yet these communities were never consulted before the concession law was passed.

A thin, muddy trail winds its way up past the old one-room schoolhouse, where a small boy pees off the front porch. The path continues past a traditional wood home, where a mother prepares a lunch of boiled plantains and homemade cheese, to a breathtaking lookout point that peers out over the sandy beach and sea. Planted into the ground high up here is a square concrete marker. Residents say it’s one of two that Chinese workers installed in Bangkukuk while taking measurements for the canal. They’re not sure exactly what it measures or means.

“We never get no kind of information about what taking place,” said Wilson. When HKND representatives visited Bangkukuk in December, he said they told residents nobody would be relocated. But then there was talk of the port here in Bangkukuk.

“It have me worried what the government trying to do to us, to Indian, Rama people,” he said. “For me my idea I’m going to fight it till the last as president.”

The simple, rectangular wood homes in Bangkukuk are sturdy with thatched or corrugated metal roofs. Inside, the few possessions are tidily arranged: a shelf of clothes, some pots, a hammock, a toothbrush, three plastic stackable chairs, a few plates. The homes rest on stilts that create a shady nook for pigs, chickens, roosters and dogs to nap. Women and children gather in the afternoon for a lively game of baseball with a makeshift bat and ball. A diapered toddler joins the excitement, running happily among the players.

“We as Rama we just live we life as you see here — we work, we plant, eat, and we live. We don’t go molest nobody,” said Gregory Ortiz Hodgson, vice president of Bangkukuk’s seven-person communal government. “And if the canal come to move we, many of we is worried, because we no accustomed to live another way. We no accustomed to live another life different than this. We live here free.”

But amid the free-roaming animals and lilting Creole and children’s laughter is also damning evidence of an entire region long neglected.

More than half the population in the rural areas of the Caribbean coast are illiterate (compared to a quarter of the country as a whole), and three-quarters live in poverty or extreme poverty, according to the Foundation for the Autonomy and Development of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua. The nonprofit estimates as much as 80 percent of average salaries along the coast are used to purchase food.

Scroll for more

Scroll for more

Scroll for more

Scroll for more

Poor infrastructure is endemic: According to a 2011 World Bank analysis of the autonomous region, the Caribbean Coast makes up 46 percent of the country’s national territory but contains only 8 percent of its roads. While Rama make up only about 2 percent of the region’s population, the report also states that 100 percent of Rama youth face chronic malnutrition.

Ortiz says he has not yet come out in favor or against the canal. He wants first to see the central government respect the indigenous communities and explain every detail of the project, so the Rama-Kriol people can negotiate a fair settlement.

“When we talk, listen to we. Listen to our needs and the meaning why we don’t want to leave here,” he said. “It’s big effect what happening to we. OK, if it’s big effect and we can never stop it, make what the government going to give value like what we going to lose.”

He hopes the community will make an informed collective decision. He sees it as an opportunity to create a better future for the next generation of Rama, but concedes that it also “gives some of the older people sadness to tell them that they will banish the land from we.”

“I pray to God, make the canal — they can make it — but they must not move us,” said Angela Benjamin, 65, sitting on her porch looking out at the ocean. “We grow here, all of we, because we one family. So I don’t want make no one move from here.”

Benjamin, one of last Rama speakers, grew up speaking the language at home.

“My mother is Rama,” she said. “Only Rama she speak with we. When I was a little girl coming up I couldn’t speak Creole — only Rama I speak.”

Benjamin married a Miskito man, and said she now speaks only Creole with her children and grandchildren. “But when I meet with my sister and my cousin we talk Rama,” she said. “But not all speak Rama — only about six of we speak Rama. Some understand but them no talk.”

An endangered language

Rama is a nearly dead language that belongs to the Chibchan family of languages of Central America and Colombia.

“Don Pedro” McCrea is one of the six remaining speakers Benjamin mentions. As the cacique, a chief elder of sorts, the unofficial last word in Bangkukuk rests with him. He tells of how the contras captured him during the war, accused him of being a Sandinista and tied him up in the bush. He escaped at night, he said. He survived Hurricane Joan in 1988, which pounded Nicaragua's Atlantic Coast. “War, hurricane, I stay right here in Bangkukuk with all my children,” said McCrea.

“Things happening that I never see come before,” he continued wistfully, referring to the canal. “That big project come in, it going damage everything — we lose the language, we Rama language.”

He speaks of the mestizo people that have taken over swathes of the indigenous territory, killing one of his sons during a dispute in the bush a couple years ago.

“We have a little piece yet right now, to the edge,” he said, “but maybe when this project come … we no have nowhere to go.”

Most of Nicaragua’s indigenous peoples were conquered by the Spaniards in the 16th Century, but not the Atlantic Coast, which today is home to mestizos, Miskitos, Creoles, Garífunas, Ulwas and Ramas. It is legally autonomous, governed by communal and regional indigenous councils.

Recognition of the indigenous and Afrodescendent communities and their right to maintain their culture and languages is enshrined in Articles 5, 89 and 180 of Nicaragua’s 1987 Constitution. (Historically, however, the region has long been ignored by Managua, which has instilled a deep resentment for generations. That led many Miskitos, for example, to fight for the contras and against the government Sandinistas in the 1980s.) Additionally, Law 28 grants autonomy and Law 445 guarantees communal property rights as well as “the use, administration and management of traditional lands and their natural resources.”

“They have the right to their culture, to their own languages, to access to their natural resources and their land that they have traditionally used and occupied,” said Maria Luisa Acosta, an attorney for the Center for Legal Assistance to Indigenous Peoples (CALPI) who has represented indigenous communities in Nicaragua for the past two decades. “They have their own laws, internal laws, and the right to self-determination in the sense of deciding who their own government is going to be.”

Acosta says international standards — such as the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (which Nicaragua signed onto in 2008), and the American Convention on Human Rights — require the Nicaraguan government consult indigenous communities on projects that will directly impact their lives and livelihoods and reach “free, prior and informed consent.”

“That’s not happened and that’s what the law requires.” said Acosta. “They should have consulted these people, the indigenous people.”

Note: Not all homes in Bangkukuk are visible in satellite image.

The Nicaraguan government began the consultation process in December. It contends it did not reach out to the communities earlier as it wanted to see the decided route to know which specific authorities to address.

Johnny Hodgson, regional FSLN secretary and a presidential delegate for the South Caribbean, told Al Jazeera he could not comment on the status of the consultation until it is completed.

However some insight can be gleaned from the letter Nicaragua’s Attorney General Hernan Estrada sent to GTR-K President Hector Thomas Mcrea dated January 27, 2015. The letter references Law 445, quoting Art. 24 in which the state recognizes the indigenous and Afrodescendent communities’ rights over traditional lands and guarantees their protection.

Estrada goes on to state that, based on Law 445, “we reaffirm that the areas of communal property of the Rama-Kriol people will not be subject to expropriation or confiscation. Rather, “the commission expresses its readiness to establish through free, prior and informed consultation a process of dialogue and negotiation to define a perpetual lease for use of the geographic area affected by the project.”

But members of the GTR-K have been dissatisfied with the consultation process from the beginning. In December 2014 they drafted a protocol, or lineamiento, that outlines how the canal consultation must be carried out with the indigenous communities in the territory. For prior and informed consent, the protocol requires the consultation be open to all members and communal and territorial authorities, that it is culturally and linguistically appropriate, and technical assistance is provided to help the communities where education is limited. An independent international observer must also ensure the process is done in good faith.

Rupert Allen Clair Duncan, a Rama-Kriol government leader in nearby Bluefields, says the protocol has been ignored, and that the government is rushing the consultation and trying to manipulate certain leaders.

“Maybe you have under-the-table payments but we can’t prove,” he said. “We imagine that’s what they’re doing.”

Telémaco Talavera, spokesperson for the Nicaraguan government’s Grand Canal Commission, says the consultation process follows legal requirements and is highly participatory. “In the case of the properties, the consultation will be with each person. With each community. There is nothing more transparent than talking with each person, and that’s what we’re doing. We’re not discussing with those who are called representatives, but with the people themselves. So as to guarantee that everyone that is on the route, and that isn’t along the route, is left better off socioeconomically than they are now,” he said. “If a community has to be relocated, they would be guaranteed a better situation than they have now.”

When the roosters make their noisy rise each morning, so does Edwin McCrea, who gets his boots and machete and sets off on a 45-minute hike through the rainforest to the plantation where he grows yucca and bananas.

“This earth good for anything,” said McCrea. “You plant many thing in it and it produce. You can plant tomatoes, you can plant melons, you can plant anything. This is good land. This land produce a lot of things for we.”

Edwin McCrea: 'It will destroy we'

But protecting this land and all the animals in it is getting harder every year. A commission from the Nicaragua government is due to arrive soon in Bangkukuk to continue the consultation with the community. They’ll have a lot of explaining to do.

“It will destroy we. When I mean it destroy we we’re not going to get turtle, we’re not going to get fish, we’re not going to get lobster, we’re not going to get shrimp, and from the bush we’re not gonna got deer, we’re not gonna got gibnut [a rodent weighing up to 30 pounds], we not have no kind of animal if the canal come.”

McCrea believes the people who support the canal project are motivated by money, but they’re missing the big picture — the need to protect Indian rights, the flora and fauna, and the land that should be destined for Rama children.

Back in the town, confusion, anger and paranoia about the canal project is at a high ahead of the government visit. Some residents refuse to give their name, fearing any outsiders are representatives from the canal trying to use their names to prove consent to the project.

“Canal people are liars you know,” said a woman mopping her front porch. “Canal people only eating people’s brains.”

Over at the schoolhouse, a Rama woman becomes livid when the canal issue is raised.

“We Indian no want a canal,” she said, clutching a bamboo walking stick. “When Daniel [Ortega, Nicaragua’s president] take we and throw we out, where we going? … Daniel take the money and pocket it and run. And then we stay and suffer."

Watch: 'Indigenous community in Nicaragua threatened by canal proposal'